It was a clear, cold night in April 1912, when history was made. A powerful steam ship, cutting through the waters of the Atlantic at speed, met a towering iceberg, moving south at a much slower but no less deadly rate. The result was unthinkable; the unsinkable ship slipping beneath the waves less than three hours after their encounter, taking almost 1,500 lives with her.

The legend of the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic, built at Harland & Wolff in Belfast, launched at Southampton and bound for New York, is now woven into the history of the world. Thousands of pages of newsprint, hundreds of books and dozens of filmed versions have told the story from countless points of view in the one hundred years since the fateful night of April 14th/15th 1912. And yet with the recent controversy over the sinking of the luxury liner Costa Concordia in January 2012, have we really learned anything from the tragedy of the Titanic?

This is not the first time that The Post Hole has looked at the Titanic; the previous article (in Issue 5) concentrated mainly on the aspects of salvage of items taken from the wreck site and questions whether it should be protected from any and all visitors (Rounce, 2009). With the centenary of the sinking less than a month past, I wish to look more at the history of the vessel, and of its rediscovery in 1985 as an archaeological site, after over 70 years away from public gaze.

Firstly, here are some basic facts about the ship and its fate. Titanic was launched from Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast on 31st May 1911, and for the rest of the summer and autumn months went through the process of 'fitting out', whereby the interior and exterior of the ship was completed (Eaton & Haas 1987, 57-60). The launch date was set for 20th March 1912, but when her sister ship Olympic was in a collision with another vessel and had to be repaired in Titanic's dry dock, it soon became apparent this date could not be met (Eaton & Haas 1987, 60-61). A new and fateful date was decided: 10th April 1912 (Eaton & Haas, 1987, 61). Sea trials took place on 2nd April 1912, before setting course for Southampton (Eaton & Haas, 1987, 62-66).

The ship itself was huge, almost 900 feet in length and weighing 46,000 tons; it took three million rivets to keep her together (Wade, 1986, 18-19). Her system of watertight compartments, which could be closed by a switch on the bridge, led to Titanic being described as "practically unsinkable" by the newspapers Irish News and Belfast Morning News in June 1911, a claim taken up by the magazine Shipbuilder later the same month (Lord, 1987, 28). However, these compartments only reached as high as Deck E, and given enough water, the ship could be 'over-topped' (Lord 1987, 75-77).

Titanic set out on her maiden voyage on Wednesday 10th April 1912 under the captaincy of Edward John Smith, bound first for Cherbourg, then for Queenstown, before heading off into the Atlantic, due to dock in New York a week after setting out, on Wednesday 17th April (Eaton & Haas, 1987, 83-84). She steadily increased speed as the days passed, covering 386 miles in the period between noon April 11th and noon on the 12th, 519 miles in the next twenty four hours and 546 miles for the twenty four after that (Eaton & Haas, 1987, 92). Then, just before midnight on April 14th, an iceberg was spotted by the lookout directly in the ship's path, and despite the best efforts of First Officer Murdoch on the bridge, Titanic caught it a glancing, but fatal, blow (Eaton & Haas, 1987, 15-16).

In the next two and a half hours, before the liner slipped beneath the waves at 2.20am on April 15th (Lord, 1986, 149), just 711 passengers and crew were saved, leaving almost 1,500 to perish in the icy waters of the North Atlantic (Lord, 1986, 92). This is a very small number of survivors as, even though there was only lifeboat space for 1,178 (nowhere near the vessel's capacity (Lord, 1986, 83)), many of the boats that left were nowhere near full (Gracie, 1985, 261-262). It is fortunate that, due to a coal strike in England that was settled just days before Titanic left port, the ship was not filled to its capacity of 3,547 passengers and crew, or the disaster could have been much worse (Lord, 1987, 83).

There were twenty lifeboats floating among the ice field that was now drifting over the grave of Titanic (Wade, 1986, 180). Captain Smith, Chief Officer Wilde and First Officer Murdoch had gone down with the ship, leaving Second Officer Lightoller, who had been swept into the sea as the ship went down, as the highest ranking surviving officer (Gracie, 1985, 60-61 & 81). Just after 4am, the liner Carpathia responded to Titanic's S.O.S. message, and arrived on the scene and picked up the first boatful of survivors (Eaton & Haas, 1987, 41). The last set of survivors was collected at 8.30am (Gracie, 1985, 113).

There were inquiries on both sides of the Atlantic in the aftermath of the tragedy (Gracie, 1985, 114-323; Wade, 1986, 69-260), but after a while Titanic seemed to slip out of public consciousness for many years, until an awakening of nostalgia caused a return to the values of the time, and the Titanic spirit seemed to be reborn (Lord, 1987, 18).

Many writers have placed their own fictional 'spin' on Titanic over the years, with numerous film and stage productions of the story (Lord, 1987, 14). It was used by popular BBC television series Upstairs, Downstairs in the 1970s to kill off a major character, and Noel Coward also used this device in his play Cavalcade (Lord, 1987, 14-15). The fictional finding of the wreck (Cussler, 1976) and its future (Clarke, 1990) have inspired authors in more recent times.

The actual finding of the Titanic wreck site on September 1st 1985, by Doctor Robert Ballard and his team of oceanographers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, opened up a whole new life to the legend of the great liner (Ballard, 1987).

I am sure that the majority of us have seen, at least in passing, some of the stunning images taken by Ballard's expeditions (Ballard, 1987; Ballard, 1988). The ghostly form of the bow, standing upright on the seabed, appearing out of the gloom two and a half miles beneath the ocean is a once seen, never forgotten image (Ballard, 1987, 118). The crumpled and battered, but still recognisable stern section lies almost 2,000 feet away from the bow, pointing in the opposite direction (Ballard, 1987, 150-151 & 156-157). There are many items scattered around the debris field close to the stern, such as coffee cups, toilet bowls, bottles, bed fragments and part of a deck bench, among other things (Ballard, 1987, 150-151). All these evoke a sense of eerie familiarity, of ordinary life ripped away from the surface and placed at the bottom of the ocean.

A large number of visits have been paid to Titanic since its rediscovery in 1985, both by Ballard and his team (Ballard, 1988) and by others (Sides, 2012; Cameron, 2012). The ethics or otherwise of removing items from the seabed is discussed elsewhere (Rounce, 2009) but the argument can be made that the wreck area is just another archaeological site. However, if that is to be used as reasoning, then the removal of artefacts is surely akin to 'nighthawking' on a surface site.

One of the more famous names to have visited the wreck site is James Cameron, the Hollywood movie director who made the big budget version of the story in 1997 that launched the careers of Leonardo diCaprio and Kate Winslet (Titanic, 1997). He has 'dived' on the site on 33 separate occasions across three sessions, in 1995, 2001 and 2005, the latter two occasions where his revolutionary robot cameras managed to fit into much smaller spaces and areas than ever before explored (Cameron 2012, 100-109). These have provided a unique archaeological view of the famous wreck, having covered 65% of the interior that still survives (Cameron, 2012, 100-109).

So, what is the legacy of the Titanic? In an immediate sense, the provision of lifeboats on all ships for all passengers and crew was a major advance (Lord, 1987, 86-87). It was also a timely reminder that when man tries to triumph over nature, nature usually wins out. Ships still founder today, even with all our satellite imaging, mapping systems, sonar and deep scanning technology; we are still powerless against the raw power of nature to put man firmly in his place.

But probably the best legacy is to remind us that even in adversity, the human spirit endures. The courage, bravery and heroism displayed on that freezing April night has lived on in the eye witness accounts, told and retold in the film, television, stage and book versions of the story through the last one hundred years. That legacy will go on.

Bibliography

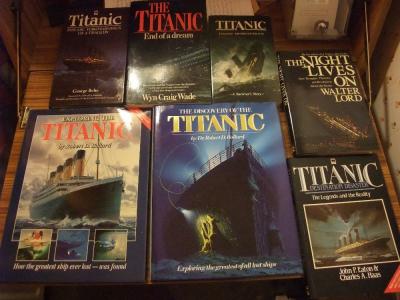

- Ballard, R. D. (1987). The Discovery of the Titanic. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Ballard, R. D. (1988). Exploring the Titanic. London: Pyramid Books.

- Cameron, J. (2012). 'Ghostwalking in Titanic'. National Geographic, 221 (4), 100-109.

- Clarke, A. C. (1990). The Ghost from the Grand Banks. London: Orbit.

- Cussler, C. (1976). Raise the Titanic!. New York: Viking Press.

- Eaton, J. P. & Haas, C. A. (1987). Titanic: Destination Disaster — The Legends and the Reality. Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens Limited.

- Gracie, A. (1985). Titanic: A Survivor's Story. Gloucester: Alan Sutton Publishing.

- Lord, W. (1987). The Night Lives On. Harmondsworth: Viking Press.

- Rounce, D. (2009). 'How human intervention is harming the wreck of R.M.S. Titanic, and how the site is protected by law'. The Post Hole, 5, 15-17.

- Sides, H. (2012). 'The lights are finally on'. National Geographic, 221 (4), 86-99.

- Titanic (1997). Directed by James Cameron [Film]. Los Angeles/Hollywood (Los Angeles)/Santa Monica (Los Angeles): Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation/Paramount Pictures/Lightstorm Entertainment.

- Wade, W. C. (1986). The Titanic: End of a Dream. London: Weidenfeld Paperbacks.