Dr Cath Neal is an archaeology fieldwork officer at the University of York, and has worked on all the seasons at Heslington East.

For the last four years many of us in the department (students, volunteers and staff) have been working on the 116 hectare greenfield site of university expansion at Heslington East. Well, I hear you all ask, what did we find? Currently we are in the middle of writing the Assessment Report for the site (and still awaiting some specialist reports and further analysis). Here, at this interim stage, I have outlined some of our archaeological findings but wanted to also highlight some of the wider benefits of the work. It would be a cliché, but however still true, to say that whilst we found out quite a lot about the archaeology of the site we also found out quite a bit about ourselves; working to a common aim through the sunshine, showers and hail (and not forgetting, of course, the torrential rain of 2010).

This rural site offers a unique opportunity to understand multi-period settlement, and its landscape setting, in the Vale of York. Fieldwork was carried out here jointly by York Archaeological Trust (YAT), On Site Archaeology (OSA) and the Department of Archaeology (University of York) between 2007 and 2011 and is currently in the analysis phase. When this is complete it will add substantially to the corpus of data about York's hinterland, from prehistory until the end of the Roman period. It will also add detail to a range of period and thematic research questions, and lead to popular and academic publications.

Introduction to the archaeological evidence

There are currently several active spring heads on the hillside and geoarchaeological work undertaken on the site where YAT were working has identified a series of early palaeochannels running down the slope north-south, which probably created an area of standing water to the south beginning in the early post-glacial period (Carey 2009, 168). This may have been a wetland mosaic which contained a variety of vegetation and attracted wild fowl. Some of the archaeological definition on the site was complicated by a series of hillwash sands and silts that sealed and masked archaeological deposits, which effectively cut from different levels. These colluvial deposits vary in depth with the morphology of the hill-slope but also vary significantly in their lateral extent and depth. Students excavating on the site will remember only too well the difficulties of defining some of these elusive and masked features, and trying to distinguish the subtly different sands!

The earliest evidence for human activity at Heslington East was the discovery of a number of stone implements which date from the early Mesolithic period, and include a serrated saw, though the majority of the flint and worked stone found dates to the Neolithic and Bronze Age (Makey 2009). The flint assemblage is described as significant for the Vale of York and will be subject to full analysis in due course. Landscape scale features, including some curvilinear ditches and deposits around watering holes, also date to the Bronze Age (Antoni et al. 2009). Hollowed out alder logs have been used on the springline to form probable well linings and at least one of these dates to c.3750BP (Bruce pers.comm.).

A second Bronze Age collared urn was recovered during the Department of Archaeology undergraduate field school 2011. The collared urn appears to represent Longworths 'Primary Series' with repetitive, incised herringbone external and internal decoration, it is likely that this was created with a single tool (Manby pers.comm; Longworth 1984). At the time the urn was discovered, a further cremation (without vessel) was identified to the immediate north. An initial assessment of the cremated bone is suggestive of at least an infant burial within the cremation vessel (Holst pers.comm.). Approximately forty metres from the cremations, in a sub-circular pit, half a polished Bronze Age battleaxe was recovered. This implement had an expanded butt and on initial inspection appears to be representative of a 'Stage V' Loosehowe type (Manby pers.comm; Roe 1966, 209).

Iron Age settlement evidence at Heslington East is more apparent with the discovery of the remains of several roundhouses across the site, some situated within elaborate ditched enclosures and evidence for their rebuilding on successive occasions. The primary division of the agricultural landscape also occurs at this time and a series of ring ditches are evident too (Antoni et al. 2009). Several areas around the springheads across the site are increasingly managed at this time with evidence including wattle-work fencing, revetment and deliberate cobbling. Within a substantial springhead deposit an Iron Age skull was recovered and has been subject to rigorous scientific analysis due to the preservation of human brain tissue (O'Connor et al. 2011).

Despite limited evidence for occupation at Heslington East from documentary, remote sensing and reconnaissance techniques in advance of development, there is significant Roman settlement in the form of domestic masonry and timber buildings, the use of landscape features (including large ditches, cobbled trackways and terracing) and some specialised craft activities. Other substantial structures on the site include a 3 metre deep stone lined well which was backfilled deliberately when it went out of use with a range of cattle skulls, animal bones, and ceramics including some whole pots. Also found was a probable tower mausoleum cobbled foundation, and the blocks from the site most likely associated with this utilise Roman technology usually seen in civic building within the military zone.

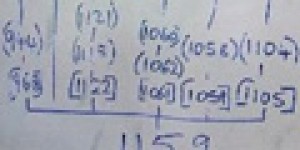

We have recovered a number of Roman burials and see, in one case, the line of an earlier boundary ditch reinforced by the insertion of two late third century inhumations. There are hints of early Roman settlement (either Romano-British or second-century activity) but the majority of the ceramic and radiocarbon dating evidence suggests a third- to fourth-century date for most of the Roman features. Evidence for immediate post-Roman activity is ephemeral, presumably largely truncated by deep ploughing, but assemblages of Anglian material are suggestive of a cemetery in the vicinity and across the site there is widespread evidence for medieval ridge and furrow which frequently cuts earlier features.

Part of the research value of the site at Heslington East is derived from its rural nature and the lack of subsequent settlement; this has led to the exceptional preservation of some classes of evidence, for example, the Roman brick and tile (McComish 2011, 38). The proportion of inbrices related to tegulae fragments and their relatively smaller size compared with the norm (for York and for Britain as a whole) merits further analysis. It is also noted that there is the frequent use of a fabric type seen rarely in York (ibid). These issues bring into sharp relief the mechanisms of supply and trade at the site and also the significance of chronological variation within the assemblage.

The wider context

The University of York has taken an innovative approach to the archaeology at Heslington East and this has largely been achieved by the division of funding to allow selected areas of the site to be evaluated more rapidly by commercial organisations (YAT and OSA), whilst other areas were evaluated over longer periods of time by students from the Department of Archaeology and by community archaeology volunteers. Although varied approaches and methods have been applied, to a lesser or greater extent, by different organisations who are responding to differing situations, the overarching aim of the project is to bring the analysis together in a single publication for the site as a whole.

The range of people who have worked on the site have been varied; paid staff (commercial and teaching staff), unpaid volunteers (students and local volunteers), homeless people from the Arclight Hostel, school children from Lord Deramore's Primary School, Badger Hill Primary School and Archbishop Holgate's School and personnel from other departments at the university. Working to a common end these groups have experienced most stages of the fieldwork process and have contributed to the overall success of the project.

In 2010 we received a 'Your Heritage' grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund to increase knowledge about the site by providing practical sessions for school children, a website, heritage information boards and popular publications at the end of the fieldwork. This has enabled us to increase the scope of community involvement and will allow us to produce, in 2013 some lasting and tangible outputs.

From the outset we aimed to make the project as accessible and inclusive as possible within the confines of a development site. We held open days for the public and for university staff, we invited schools, commuters from the local 'Park and Ride' and a range of societies and groups participated in site tours. Over the course of four field seasons work (42 months) we welcomed around 520 individuals (mainly our students) to excavate with us on the Department of Archaeology part of the site, and we had an additional c.350 visitors to look around the excavations. We have given 17 local society talks about the archaeology at Heslington East and have participated in several academic conferences in the UK, and also in Europe. In June 2012 the project will be presented, by invitation, to the Archaeology in Contemporary Europe conference 'Integrating Archaeology' in Frankfurt.

We have also welcomed scholars from other departments at York (chemistry and physics), other institutions (Durham University, Stanford University, the Council for British Archaeology) and other disciplines (British Geological Survey) to the site, aiming to increase understanding through sharing information, sharing skills and developing research ideas together.

In 2010 we welcomed 100 local children to the site as part of their transition programme from primary to secondary school, funded by the HLF; they undertook a range of activities including geophysical survey, excavation and recording but the most popular activity was the construction of a Roman kiln and the production of some 'Roman' pots. The children used classroom skills in practice and met new people. They enjoyed being outside and thinking about what their neighbourhood used to be like. A head teacher from one of the schools said, 'The school has benefited greatly from the expertise, creativity and opportunities the Department has shared with our learning community'. The effect of participating was also apparent in the way that experiential learning promotes enquiry, with the children asking questions such as 'how do we know?' and 'what is the evidence?' and then producing a film about Roman culture.

Two workshops were undertaken, with community participants, to seek feedback about the most significant part of their experience working on the site. In addition to gaining archaeological knowledge and skills, and enjoying working on specific archaeological features, a number of transferable skills were described, including problem solving and team work. Lying above this, however, were several higher order concepts to do with a sense of belonging, concerns over ownership and ideas about memory and landscape.

Conclusions

Cited as an example of good practice in community archaeology (English Heritage 2009) we have aimed to engage volunteers with all stages of the fieldwork process, encouraging them to have an impact on the final outputs and interpretations. The site at Heslington East, its archaeology, the collaborative approach taken and the levels of participation from various sectors of the community is an important example of the way that archaeological fieldwork is changing in the 21st century. We anticipate that the benefit of this more diffuse approach to evaluation will be felt not only in our understanding of the archaeological features themselves but also in the breadth of our understanding about 'what archaeology does' for local communities and the impact that it can have on a local level.

Bibliography

- Antoni, B., Johnson, M. & McComish, J.M. (2009). 'Heslington East, York Assessment Report', Unpublished Report, York Archaeological Trust 2009/48.

- Carey, C. (2009). 'Geoarchaeological assessment' in Antoni, B., Johnson, M. & McComish, J.M. (2009) 'Heslington East, York Assessment Report', Unpublished Report, York Archaeological Trust 2009/48.

- English Heritage (2009). Heritage Counts. London: English Heritage.

- Longworth, I. (1984). Collared Urns of the Bronze Age in Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McComish, J.M. (2011). 'The Ceramic Building Materials and Stone Roofing Tiles from University of York Excavations at Heslington East 2008-2011', Unpublished Report, University of York Department of Archaeology.

- Makey, P. (2009) 'Flint' in Antoni,B., Johnson,M. & McComish,JM. (2009) 'Heslington East, York Assessment Report', Unpublished Report, York Archaeological Trust 2009/48.

- O'Connor, S., Ali, E., Al-Sabah, S., Anwar, D., Bergström, E., Brown, K. A., Buckberry, J., Buckley, S., Collins, M., Denton, J., Dorling, K. M., Dowle, A., Duffey, P., Edwards, H. G.M., Faria, E. C., Gardner, P., Gledhill, A., Heaton, K., Heron, C., Janaway, R., Keely, B. J., King, D., Masinton, A., Penkman, K., Petzold, A., Pickering, M. D., Rumsby, M., Schutkowski, H., Shackleton, K. A., Thomas, J., Thomas-Oates, J., Usai, M.-R., Wilson, A. S. and O'Connor, T. (2011). 'Exceptional preservation of a prehistoric human brain from Heslington, Yorkshire, UK'. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38 (7), 1641-1654.

- Roe, F.E.S. (1966). 'The Battleaxe Series in Britain'. In Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society XXXII, 199-245.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to the students, staff, volunteers, York Archaeological Trust, Onsite Archaeology, the specialists cited here, Steve Roskams, John Oxley and Patrick Ottaway.