Introduction

As a country, England has a wealth of archaeological sites and important historic monuments and artefacts, for example the princely cemetery of Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, Ice Age rock art at Creswell Crags in Nottinghamshire, and the largest find of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork ever found, the Staffordshire Hoard. However, when the location and significance of archaeological sites in England are considered, a huge majority appear to be from the south and east of the country. Very little research has been undertaken into remains from North-West England, particularly that of Lancashire.

Consequently, this article will aim to inform the reader on three of the most important, yet neglected, finds from North-West England that have perhaps been cast under the shadow of other more recent discoveries. It will indicate future areas of improvement and investigation, therefore highlighting that this region is just as archaeologically noteworthy as the rest of the country.

Lindow Man

In 1984, the preserved remains of a man’s body was found amongst the layers of peat on Lindow Moss in Cheshire (Brothwell 1986, 9, 14) (Figure 1). This sparked large scale media coverage and archaeological reports, such as that by Connolly (1985) just a year later. Radiocarbon dating reported the body as being over 1,000 years old at the time of discovery (Brothwell 1986, 16), making it not only a significant find for the north-west, but nationally and internationally as well. Comparisons were immediately made with those of Tollund Man and Grauballe Man from Denmark, in order to analyse differences in decay, cause of death, and diet (Brothwell 1986, 20). Scientific investigations quickly deduced the man’s height, age and predicted facial features (Connolly 1985). Other questions, though, were not so easy to answer, such as what he was doing on Lindow Common and how he had died. These questions have contributed to debate over the years. One interpretation has been that he was killed as part of a ritual sacrifice, due to analysis of stomach remains showing that a good meal was eaten not long before death, as well as an intricate method of killing – two blows to the head, garrotting and neck slitting (Brothwell 1986, 25-29). Subsequently, Lindow Man had placed the north-west on the map. However, he is still perhaps not as well-known as he should be.

Even though in recent years, Lindow Man has made an appearance back in the North at Manchester Museum (Kirby 2007) and has been displayed at the British Museum for ten years, it was only briefly that he “came home”.

The lack of research into the Iron Age in the North-West is preventing further interpretation of the archaeological context and environment of the area, thus prohibiting the overall knowledge of the period. Excavation of hill-top settlements is extremely rare, and only a few Iron Age sites are known in Merseyside and Greater Manchester (Haselgrove 1996, 66). It would seem that there is a gap in the archaeological record which needs to be filled. This is also true for earlier prehistory in the north-west of England. Evidence for Palaeolithic activity in Lancashire is limited to that of a few blades and barbed points from Lindale Low and Poulton-le-Fylde (Cowell 1996, 21), and only a handful more Mesolithic and Neolithic sites have been found. One such example is near Chorley on Anglezarke Moor, where two long barrows are sited – one has been named as the Pikestones (Middleton 1996, 41). Unfortunately, the monument has been badly damaged, which highlights other issues with conservation and management in the region.

On the whole, prehistoric activity in the North-West was clearly occurring as has been shown via the presence of Lindow Man. To some extent, it remains a topic of debate today, with Hutton (2011) reviewing the situation, and whether the interpretations of the late 20th century can still be upheld with new theoretical perspectives. On the other hand, there is a worry that if not enough research is invested into the area, it will become neglected, and therefore focus will remain on other parts of the country.

Bremetenacum – Ribchester Roman Fort

Another archaeologically significant site in the North-West that is perhaps not as well-known, is that of the Roman fort and settlement at Ribchester, Lancashire. There has long been interest in the archaeology of Ribchester by antiquarians, but only since the 19th and into the 20th century have excavations been carried out systematically to gain sufficient records (Ribchester Roman Museum N/A). Some of the features found at the site include the bath house (Figure 2), which was discovered in 1837 in the garden of Dr. Patchett, the main fort complex dated to AD70s, and an extramural settlement (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 7).

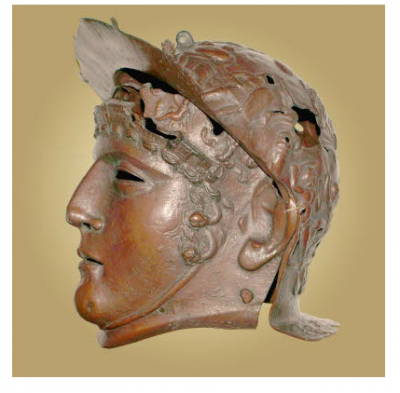

Some extraordinary artefacts have also been found from the Roman fort, including the Ribchester Helmet (Figure 3), pottery, metalwork and leather remains. These, together with the structural evidence, have provided archaeologists with the material to establish a detailed chronology for the site (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 4).

Consequently, ‘Bremetenacum’ has been identified as being a strategically important location that would have been part of trade and military routes between Manchester and Chester to the south, and Hadrian’s Wall in the north (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 3). The most recent investigations in 1980 and 1989-90 were carried out by the then Cumbria and Lancashire Archaeological Unit, which aimed to discover the nature, function and status of the fort, along with attempting to understand the relationship between the Roman soldiers and the indigenous population (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 9-10). It found that there was a certain degree of industrial activity on the site from the metalworking debris and the leather remains, which suggests primary production for the fort, but the increase in metalwork around AD120-25 indicates the possible manufacture and transport of goods for military purposes (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 419). Many metal objects were associated with equestrian activity, thus indicating that Ribchester must have supported elite cavalry troops during its period of occupation (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 247). These were thought to have been Sarmatians, and the site became very important in the governance and administration of the area (Ribchester Roman Museum, N/A).

Clearly, this archaeological site should be marked as an important location beyond the region of the North-West. It had a significant role to play in communication links for the Roman Empire in England and in learning to understand the relationships between civilians and soldiers.

Although many investigations have taken place, the earlier work is plagued with loss of information and lack of adequate recording, making it difficult to understand what has been studied before, and how it relates to later work. In addition, there have been no large full scale excavations and it has been limited to areas to the north and east of the site due to development (Buxton and Howard-Davis 2000, 4). There is still much that ‘Bremetenacum’ has to offer, particularly on the native-army socio-cultural divide, and this aspect remains illusive across the whole of the county (Buxton and Shotter 1996, 89).

Overall, evidence from Ribchester shows the extent to which important activities were taking place on the site, and how it was instrumental in transport and commuincation routes for military purposes. The interpretation of elite occupation further enhances the status and prominence of the fort within the regional landscape. Plans are currently in place for further investigations at ‘Bremetenacum’, consisting of excavation and geophysics (per comm. Noon 2013). This site therefore, should indicate the North-West as a signifcant part of Roman England, and Ribchester could be acknowledged more within a national context.

Silverdale Hoard

In September 2011, a hoard of over 200 pieces of Viking silver was discovered in a field near Silverdale. This was an amazing discovery and the finder reported it straight to the Finds Liaison Officer for Lancashire and Cumbria. Inside the container in which the metalwork was deposited, was a variety of different pieces of material, including arm-rings, coins, ingots and other jewellery fragments (Figure 4) (Boughton 2011). Due to the quality of the silver, it was declared as ‘Treasure’ and offered for museums to purchase, with the finder and landowner paid an equal sum for the value of the hoard. Analysis of the artefacts was conducted and the record can be found on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database. The ‘hacksilver’ shows Viking contacts from Ireland in the west, to Russia and the Islamic world in the east, indicating a vast network of trade and exchange (Ager and Williams 2011). It has also been compared with the other substantial hoard from the North-West, the Cuerdale Hoard. Many of the Silverdale pieces are similar, and both hoards have been given a comparable date of burial c. 900-910 (Ager and Williams 2011). Consequently, one interpretation for the collection of metalwork is that it may have either been a treasure chest from Dublin after the Scandinavians were ousted from the city, or it could equally have been intended as a payment to re-gain and conquer Dublin at a later date (per comm. Noon 2013). Either way, this finding is especially exciting for the history of Viking activity in the North-West.

More recently, the Silverdale hoard has been receiving increased public interest and media attention due to being displayed at Lancaster City Museum, and as of February 2014, is now on show at the Museum of Lancashire in Preston. It is also scheduled to be conserved at the end of the year to ensure no additional damage or deterioration of the metal occurs (per comm. Steels 2013). Hopefully, this will create more awareness on archaeology in the area and that people will visit the museum in order to learn about the hoard and its history.

Again, this archaeological discovery is not as familiar to the wider community as perhaps the Cuerdale Hoard is, and it lacks the acknowledgement it deserves in regards to the early medieval history of Lancashire. It supports the theory of wealthy Scandinavian migrants, likely arriving from across the Irish Sea, establishing settlements in the North-West around the Wirral, Chester and the Isle of Man (Philpott and Graham-Campbell 1990, 26-7). However, research on Viking activity here, appears to be to a lesser degree than in the east, which means important information has the potential to be neglected when it could be assisting in overall understanding of regional Scandinavian occupation and identity.

As a result, the Silverdale Hoard is an exceptional find that has the possibility of teaching us about wealth, economy and identity in early medieval Lancashire. The relationship with the Cuerdale Hoard further increases the significance of the metalwork, and the fact that the silver has origins from across Europe into the East shows how mobile and influential the Vikings were. With the current exhibition at the Museum of Lancashire, this discovery should become better known among not only the academic profession, but also the general public too.

Conclusion

These three notable archaeological case studies should demonstrate the variety of material available for investigation in North-West England. They each date to differing time periods, and have their own reasons for being significant. The north-west should not be seen as an area of the country with few remains, and that the landscape prohibits investigations to take place, or even that it is only useful to understand industrial archaeology. There is much more that can be gained from in-depth research, and improved field surveying and excavation procedures. These will then provide the area with more up-to-date publications, rather than pieces that are now almost 20-30 years old.

Neglecting a piece of archaeology holds the risk of forming inadequate and unreliable conclusions, so should be sought to be avoided. It also has the potential for being at risk if the correct preservation and conservation procedures are not implemented. Subsequently, this article has aimed to highlight how important finds in the North-West can be, and hopefully will have persuaded some that it is not a region to shy away from, but should be embraced in order to reveal how archaeologically rich it can be.

Bibliography

- Ager, B. a. (2011, December 15). Hoard. Retrieved from Portable Antiquities Scheme: http://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/462949 [Accessed 15th January 2014].

- Boughton, D. (2011, September 18). Hoard. Retrieved from Portable Antiquities Scheme: http://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/462949 [Accessed 15th January 2014].

- Brothwell, D. (1986). The Bog Man and the Archaeology of People . London: British Museum Publications.

- Buxton, K. a. (1996). Roman Lancashire. In R. Newman, The Archaeology of Lancashire: Present State and Future Priorities (pp. 77-89). Lancaster: Lancaster Archaeological Unit.

- Buxton, K. a.-D. (2000). Bremetenacum: Excavations at Roman Ribchester 1980, 1989-1990. Lancaster: Lancaster University Archaeological Unit.

- Connolly, R. C. (1985). Lindow Man: Britain's Prehistoric Bog Body. Anthropology Today, 1(5), 15-17.

- Cowell, R. (1996). Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Lancashire. In R. Newman, The Archaeology of Lancashire: Present State and Future Priorities (pp. 21-31). Lancaster: Lancaster Archaeological Unit.

- Haselgrove, C. (1996). Iron Age Lancashire. In R. Newman, The Archaeology of Lancashire: Present State and Future Priorities (pp. 61-71). Lancaster: Lancaster Archaeological Unit.

- Hutton, R. (2011). Why does Lindow Man matter? Time and Mind, 4(2), 135-148.

- Kirby, D. (2007, February 15). Lindow Man comes home to his roots. Retrieved from Manchester Evening News: http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/lind... [Accessed 10th January 2014].

- Middleton, R. (1996). Neolithic and Bronze Age Lancashire. In R. Newman, The Archaeology or Lancashire: Present State and Future Priorities (pp. 35-55). Lancaster: Lancaster Archaeological Unit.

- Museum, R. R. (N/A). Archaeology. Retrieved from Ribchester Roman Museum: http://ribchesterromanmuseum.org/html/archaeology.html [Accessed 10th January 2014].

- Museum, R. R. (N/A). Roman Ribchester . Retrieved from Ribchester Roman Museum: http://ribchesterromanmuseum.org/html/roman_ribchester.html [Accessed 10th January 2014].

- Philpott, F. A.-C. (1990). A Silver Saga: Viking Treasure from the Northwest. Liverpool: National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside.