The bridge chapel in Wakefield, Chantry Chapel, has been a Grade I listed building since 1953, and Wakefield Bridge is a scheduled ancient monument (English Heritage, nd). This report documents the results of a desk based assessment, visual analysis and phased interpretation of the Chantry Chapel. The aim of the study was to determine the nature of construction, alterations, repairs and maintenance from its construction to the present day, setting them in their wider context, and enabling an interpretation of the phasing of the building.

Historical development

A chantry chapel is a chapel which contains a chantry (an altar) where priests chant masses for the founders and their families during life, and for their souls after death (Speak and Forrester 1971, 29; 1972, 4). Four chantry chapels were built in Wakefield before 1400, but the Chantry Chapel of Saint Mary is the only one that remains (Speak and Forrester 1971, 25). It is thought that this is because the chapel is an integral part of the medieval Wakefield Bridge, and it is important to the bridge’s structure, acting as a buttress (Speak and Forrester 1972, 4). According to Pevsner (Pevsner and Radcliffe 1967, 529) one of the reasons chapels were built on bridges in medieval times, was to collect money for the upkeep of the bridge.

During the 14th century, Wakefield flourished and the town boasted a parish church, four roads leading into it, and around 120 houses (Speak and Forrester 1971, 22). The Chantry Chapel was built, along with Wakefield Bridge in 1342 at around the same time as the nearby Parish Church and Sandal Castle. It is believed that the people of Wakefield built the Chapel and it is speculated that the same stonemasons built all three buildings, the Chantry Chapel being their highest success (Walker 1967, 228).

Notable architects, antiquarians and historians of the 19th century subsequently considered the design of the front, in the English Decorated Style, to be one of the best examples of fourteenth century architecture (Speak and Forrester 1972, 5) and the flowing tracery, crockets and reliefs have been described as the most flamboyant in the country (Glossop 2012, 211).

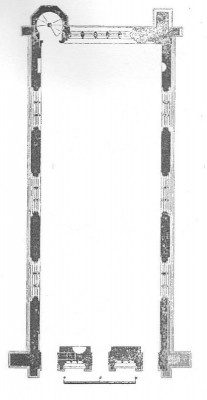

The sandstone building stood on a small island in the River Calder, adjoining Wakefield Bridge. It measured 50’ long by 25’ wide by 36’ high and contained two rooms – a crypt or sacristy at lower level, and a chapel above. Internally, the chapel measured 42’ long by 16’8” wide and the crypt, under the eastern third of the building only, measured 16’ wide. An octagonal turret to the northeast corner contained the staircase connecting the two spaces and the bell tower above (Walker 1967, 234).

The west façade was the front of the building, accessed from the bridge via two steps. At each side were buttresses, with five arched and highly decorative panels between. The northernmost, middle and southernmost arches contained doors and those in between were solid but with tracery. The parapet was also divided into five panels, each containing a relief sculpture, and topped by crenellations. The parapet corners each contained a niche with a statue, and the outer buttresses were topped with crocketed pinnacles, each of which had two niches with statues (Walker 1967, 234-236).

Drawn evidence shows that there was a small window above the east window on the south elevation. The east window consisted of five traceried lights, above which was a recess in the gable, containing a statue of the Virgin Mary. The three windows in each of the north and south elevations were square-headed, divided into three lights, and had flowing tracery near the head. The roof was wood with a lead covering (Walker 1967, 237-238).

Internally, a holy water stoup sat in a recess in the west wall, to the north of the central door. In the north wall, a recess with doors served as an aumbry, and against the south wall was a piscina. On the east wall, a statue of the Virgin Mary was positioned in a recess, and in front of this was a raised stone altar (Walker 1967, 238).

The Chantry was licensed in 1356, possibly having been delayed because of the Black Death (Walker 1967, 229). However, the Act for the Dissolution of the Chantries in 1545 brought a temporary end to the Chantry Chapel as a place of worship, and in 1548 it was sold, under the condition that it must not be demolished because of the structural support it provided to the bridge. By the following decade, Roman Catholicism had been revived by Queen Mary and for the duration of her short reign, the Chapel was back in use as a place of worship. At some time in the mid 16th or early 17th century, the Chantry was given to the trustees of the Wakefield Poor (Speak and Forrester 1972, 5; Taylor 2008, 108).

It appears that by 1638, the Chantry Chapel and Wakefield Bridge were in poor condition as the County Magistrates granted £80 for their repair. Walker (1967, 244-245) mentions documentary evidence in the form of a sepia drawing dating from around this time that shows the three northern windows blocked up, a missing parapet on the north, a broken parapet on the turret and front, and rough stonework infill to the lower part of the west front.

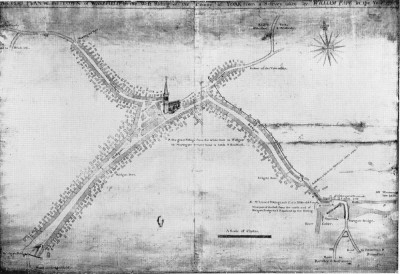

There are no maps of Wakefield before 1771, but Figure 4 gives the impression of a prospering town in the early 18th century. As one of a relatively small number of buildings identified by name on this drawing, the Chantry Chapel obviously had significance, but little is known about any building work carried out on it for most of the 18th century, possibly because it was put to a variety of secular uses between 1696 and 1842, with the records relating mostly to tenants and businesses.

Wakefield Bridge was widened twice, once in 1758, and again in 1797 (Speak and Forrester 1972, 7) indicating the importance of the route into the town. At around the time of this latter widening, on an order made at the Pontefract Quarter Sessions, the Chantry Chapel was leased from the Trustees of Wakefield Poor to the West Riding Magistrates, who were to be responsible for its repair. They were already responsible for the bridge, and since the chapel was deemed to be essential to its structural stability, it made sense that they should be under the same management (Walker 1967, 245).

The works of 1798 involved removing the infill and tracery to the original window positions on the north elevation and replacing them with new windows. At the front of the chapel, the buttresses were supported by short round pillars. There is speculation that the works carried out brought about an improvement in the status of tenants (Walker 1967, 245).

Rebuilding of the Chantry Chapel in the 19th century

In 1842, Vicar Samuel Sharp, Trustee of Wakefield Poor, proposed to the Yorkshire Architectural Society that the Chantry Chapel, once again in a state of decay, be restored. He persuaded the other trustees to give the building to the Church of England, and the magistrates agreed to relinquish their lease. An architectural competition was held and the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott won (Taylor 2008, 108). In 1847-1848, the chapel was rebuilt from bridge level upwards, mostly in its original design, but with a few small amendments: namely that the front was constructed of Caen and Bath stone, the Chapel floor was level with the bridge, the high window to the south was omitted, the southernmost parapet panel on the west front had a different relief, and the recess for the stoup became a space for the font. Stone was reused where possible, the east window and three of the side windows were filled with stained glass, and the crypt was enlarged (Walker 1967, 246-247).

The original front was relocated to Kettlethorpe Hall where it was used as the front of a new boathouse (Walker 1967, 246).

Unfortunately, Caen and Bath stone were not suitable for use in an industrial town and the front façade rapidly deteriorated to a condition worse than the original it had replaced (Walker 1967, 246).

Restoration projects in the 20th – 21st centuries

The first major restoration of the Chapel in the 20th century was carried out in 1939 under the guidance of the architect Sir Charles Nicholson. The west front was replaced, and, according to Walker (1967, 247), so also were miscellaneous stones and most of the window mullions and tracery, and the existing walls repointed. Taylor (2012, 37) reported that the statues to the west front were added in 1948 after World War II had ended, yet photographic evidence of apparently later date does not show them. Primary documentary sources do however confirm that further works were required by 1948 and that between 1950 and 1954, a programme of works was carried out under the guidance of the architect Major Pace. This included new stonework for two windows, repairs to the roof, external and internal pointing, replacement of the chapel floor/crypt ceiling, an upgrade to heating, lighting and power systems and miscellaneous minor works (Secretary’s Reports to AGM 25/4/1949, 4/4/52, 13/4/53 and 1955. WYAS, D152; Letters from Pace 7/4/52, 18/8/52 and drawings nd. WYAS, D152). It seems unlikely that replacement of the window stonework and pointing of the walls would have been carried out in 1939 and the early 1950s.

By 1966, further restoration work was required. This time the works included repair and renovation of the stonework and glazing on the north elevation, restoration of the turret and crypt walls, and pointing and glazing of the west front. Alterations were also made to the heating and lighting systems, the organ and interior furnishings (Anon. “£4,500 is Chantry’s need”, Wakefield Express 9.3.73).This work was completed in the mid 1970s (Taylor 2011, 43).

The Friends of Chantry Chapel website states that the group formed in 1990 in order to keep the chapel in a good state of repair and make it available to visitors (Taylor, nd). In 1995-6, major repairs were carried out to the roof, stonework was repaired and replaced where necessary, and the heating, power and lighting systems were replaced (Taylor 2011, 43). Work to the roof was required in 2007 when thieves stole lead and damaged the crenellations.

In 2009 the most recent restoration and new works were carried out, which included the laying of a new stone floor, removal of pew platforms, repairs to the stair, and the insertion of a new service area to the west end, housing a small kitchenette facility and a composting toilet accessed from the south door on the west front (Taylor 2011, 46-47).

The building today

Chantry Chapel and Chantry Bridge are well liked by the people of Wakefield, and act as a local landmark (Taylor 2011). Being one of only four remaining bridge chapels in the country, there is a national significance too, particularly as it is thought that the Wakefield Chantry Chapel is the best surviving example (Pevsner and Radcliffe 1967, 529).

The front façade facing the bridge is very soiled and weathered, and is a stark contrast to the other elevations which are much cleaner. Evidence of stone replacement is very clear to see, because of the lesser amount of dirt and the reduced level of decay. The condition of the older stone is quite variable, with some retaining good clarity to the highly decorative designs, and other areas severely eroded. Documentary research has provided dates for some of the replacement works, alongside information about design choices and specification.

The crypt area at the lower level shows evidence of numerous periods of change including formation of a chimney, the remains of a fireplace, and plumbing and electrical services. It also appears that the crypt has been reduced in size as the plan (figure 2) does not correspond to the current layout. Stone infill is evident, however there is no documentary evidence to explain this. The room does not have a use.

To the main chapel above, several aspects of work are evident, ranging from major changes such as a renewed flag floor and the insertion of lightweight partitioning to form a service area, to more minor changes such as the replacement of individual stones, pointing repairs and repair leads to the stained glass. The insertion of modern services (lighting, heating, plumbing and power) is evident throughout. Again, documentary research has provided dates for some of the works. However, in the case of the timber roof, which is part plain and part decorative, documentary evidence has not been found to provide an explanation as to whether this relates to phasing/authenticity issues.

Interpretation

There have been three major phases - the original building, rebuilding of the chapel from bridge level upwards in 1847, and the second replacement of the front in 1939 (Pevsner and Radcliffe 1967, 530), but there also have been numerous alterations, repairs and modernisations throughout its life. The figures below describe the external phasing.

A) The facade today, much weathered and dirtied by passing traffic, and with small areas of stone replacement evident.

B) West elevation photographic phasing diagram.

C) North elevation photographic phasing diagram.

D) South elevation photographic phasing diagram.

Conclusion

Despite its long and complex history, the fabric of the Chantry Chapel, as it stands today can be summarised as having a medieval base, mid-19th century walls, a 20th century front façade and roof, and various small to medium scale replacements and repairs dating from medieval times to the present day.

Further research will likely produce much more comprehensive information than has been provided in this report. A particularly rich source of information, although not complete, is available for the building from the mid-19th century to the third quarter of the 20th century, in the form of minute books, faculties, architect’s correspondence and dilapidation books/ quinquennial inspections, all available at WYAS. The Diocese of Wakefield retains documentation relating to the more recent works identified through visual analysis.

The removal of the original façade is controversial as it could be argued that it is not authentic to use it elsewhere and rebuild a replacement for the original building. There are also questions about how the replacement facades and elements have been designed – some have been created as a replica, others have been re-interpreted in the age in which the work was done. The former aligns with English Heritage’s principles of restoration and the latter with their guidance on authenticity and integrity (English Heritage 2008, 47; 55). The result is that the building combines elements from many periods, mostly in a style with which little of the building fabric is actually contemporary. However, the building’s history, fabric, listed status, the volume of literature, and the warmth felt by the people of Wakefield, demonstrate that it does have significance on many levels, on both a local and national scale.

Bibliography

Unpublished sources

- Church of England (1844-1995) St Mary’s Church Wakefield. Reference D152. West Yorkshire Archive Service.

- Goodchild, J. (1981). The development of Wakefield in maps, plans and views c.1680-1926. A selection made by John Goodchild. Wakefield Historical Publications No. 7. Reference D6.1. Wakefield Local Studies Library.

Published sources

- Anon. (2010). Old-maps.co.uk [Online]: Ordnance Survey. Available at: http://www.old-maps.co.uk. Last accessed on October 9th, 2013.

- Anon. (nd). Museum Collections Online [Online]: Wakefield Council. Available at: http://www.wakefieldmuseumcollections.org.uk/photographs/index.asp?page=.... Last accessed on October 14th, 2013.

- Anon. (nd). 'Twixt Aire and Calder [Online]: Wakefield Council. Available at: http://www.twixtaireandcalder.org.uk/search.htm?term=chantry%20chapel&ty.... Last accessed on October 14th, 2013.

- Glossop, W. (2012). West Yorkshire. Norwich: Canterbury Press.

- Goodchild, J. (1991). Aspects of medieval Wakefield and its legacy. Wakefield: Wakefield Historical Publications.

- Goodchild, J. (1998). Wakefield. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Limited.

- English Heritage. (2008). Conservation principles - policies and guidance for the sustainable management of the historic environment. London: English Heritage.

- English Heritage. (nd). The national heritage list for England [Online]: English Heritage. Available at: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/professional/protection/process/natio.... Last accessed on October 9th, 2013.

- Pevsner, N. and Radcliffe, E. (1967). The buildings of England. Yorkshire West Riding. 2nd ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.

- Speak, H. and Forrester, J. (1971). An outline history of Wakefield. Ossett: Harold Speak and Jean Forrester.

- Speak, H. and Forrester, J. (1972). The Chantry Chapel of St. Mary on-the-Bridge Wakefield. Ossett: Harold Speak and Jean Forrester.

- Taylor, K. (nd.) The Chantry Chapel of St. Mary Wakefield [Online]: Friends of the Chantry Chapel of St Mary the Virgin. Available at: http://www.chantrychapelwakefield.org/index.html . Last accessed on October 14th, 2013.

- Taylor, K. (2008). The making of Wakefield 1801-1900. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

- Taylor, K. (2011). The Pious Undertaking Progresses: the Chantry Chapel of St Mary the Virgin, Wakefield Bridge in the nineteenth, twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Wakefield: Wakefield Historical Publications.

- Taylor, K. (2012). Wakefield Diocese. Celebrating 125 years. Norwich: Canterbury Press.

- Wakefield Express. (1973). ‘£4,500 is Chantry's need’, Wakefield Express (9 March).

- Walker, J. (1967). Wakefield - its history and people. 3rd ed. Wakefield: EP Publishing.

![Figure 1. Engraving showing the chantry chapel on the bridge, believed to be from the 1680s (Lodge c.1680 [Engraving; Wakefield from London Road], Goodchild 1981, Item 1).](/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/600_wide/public/uploads/306/j1.jpg)

.jpg)

![Figure 7. St Mary’s Chapel on Wakefield Bridge, 1851 (Higham 1851 [Engraving; Image Reference: xl02643] At: http://www.twixtaireandcalder.org.uk). Everything from bridge level was rebuilt in 1848. Image courtesy of Wakefield Council.](/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/medium/public/uploads/306/j7 (2).jpg)

![Figure 8. The West front between 1895-1905 with the protective railings in place. Missing stonework can already be seen to the top crenellations (Garratt 1895-1905 [Photograph: Accession number: 1983.157] At http://www.wakefieldmuseumcollections.org.uk). Image courtesy of Wakefield Council.](/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/medium/public/uploads/306/j8.jpg)

![Figure 9. The Chapel between 1900-1910. The severe decay to the front is not evident on the previous photograph. Even if the photographs were taken 15 years apart the change seems very dramatic. (Anon. 1900-1910 [Photograph: Accession number: 1978.104/5] At http://www.wakefieldmuseumcollections.org.uk). Image courtesy of Wakefield Council.](/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/medium/public/uploads/306/j9.jpg)

![Figure 10. Dated between 1910-30, further erosion can be seen, particularly to the north side of the façade (Anon. 1910-30 [Photograph: Accession Number: 1993.2034] At http://www.wakefieldmuseumcollections.org.uk). Image courtesy of Wakefield Council.](/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/medium/public/uploads/306/j10.jpg)

![Figure 11. Erection of the new front in the same design as the previous front. (Anon. 1930-40 [Photograph: Accession Number: 1971.59/8] At http://www.wakefieldmuseumcollections.org.uk). Image courtesy of Wakefield Council.](/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/medium/public/uploads/306/j11.jpg)