In the early twentieth century there was very little concern for gender issues in archaeology, with men leading the study on all platforms. Leading female figures such as Garrod were not celebrated, but left out of the grand narrative of archaeological history (Hills 2004). However, gender archaeology, or enquiries into gender in the archaeological record, has grown since the 1960’s, and overtly since the eighties, paralleling the growing interest in gender issues throughout most other disciplines and socio-political life (Greene and Moore 2010). Now it is recognised that there is “no longer a simple binary divide between men and women”, with numerous cases of people being classified as a third or cross-gender (Gilchrist 1999, 54-78). Since the emergence of gender archaeology, there have been numerous phases of research and debate. This is exemplified through case studies, such as the three which I focus on in reference to this discussion; Marija Gimbuta’s works on Neolithic and Copper Age Indo-European societies’ use of the female figure (1974), Bettina Arnold’s re-examination and analysis of an Iron Age female burial (1991), and Whelan’s study of a Native American ‘two-spirit’ individual at the Santee Sioux cemetery (1991). However, when considering these case studies, we must observe both the geographical and periodic variations. Approaches to gender archaeology have varied quite obviously internationally, as is apparent when comparing Europe, the USA and Australia, as well as in the study of different time periods such as prehistory and succeeding eras (Nelson 2006). Nevertheless, “the absence of women, whether in the profession, in representations or in interpretations, was, however, the consistent theme, and the emphasis was therefore upon gaining visibility” (Sorensen 2000, 156).

The 1960’s and the emergence of the ‘second wave of feminism’ meant that the earliest approach to gender archaeology made a large effort to finally bring women into the narrative of archaeological work, which had predominantly been undertaken by Victorian male scholars. The main objective was to rectify the male bias, or androcentric assumptions. These assumptions are most apparent in the sexist use of language in archaeological books, here an exemplar from Ucko’s work; “Early man made a home in a cave… He made scrapers and bones… His wife used the scraper to clean the underside of animal skins” (Unstead 1953, 7). Thus, this representation of generalised patriarchal society needed to be altered.

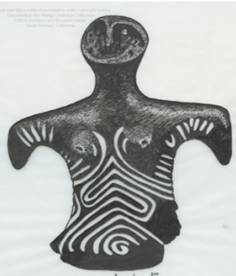

This is presented especially well in Marija Gimbuta’s work with female figurines (Fig. 1) in the Neolithic and Copper Age of south-east Europe and Anatolia (Gimbutas 1974). She concludes that the predominant number of female figurines, compared to that of male representations, demonstrates the importance of women’s status at the time. However, the fact that she did not consider, or chose to dismiss, the wider context of Indo-European society and its male dominated and warlike character, brought about much criticism of her ‘gynocentric’ approach. Sceptics such as Ian Hodder argued that “the elaborate female symbolism in the earlier Neolithic expressed the objectification and subordination of women… Perhaps women rather than men were shown as objects, because they, unlike men, had become objects of ownership and male desires” (Hodder 1995, 220). Later, this phase in gender archaeology has been labelled “add women and stir” (Wylie 1991, 34). It has additionally been highly criticised, being viewed as sometimes radical, inaccurate and gynocentric, as seen with Conkey and Gero’s (1997, 424-430) explanation of the early approach to the subject as “diverse in theory” but sometimes unnecessarily “seeing gender everywhere”, or “genderlirium”.

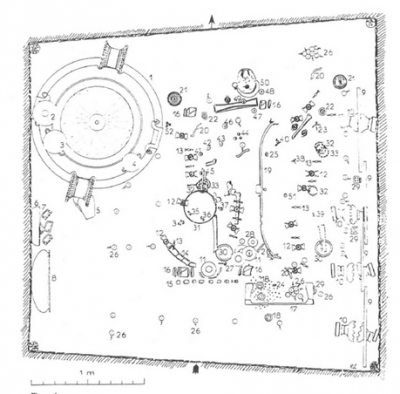

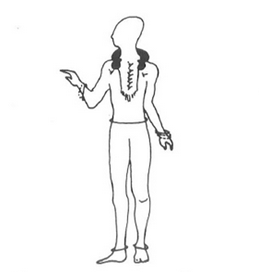

The difficulty of looking at burial goods in relation to gender or sex are evidenced by the analyses of Bettina Arnold and the ‘Princess of Vix’, French burial. Arnold (1991) carefully re-examined the grave goods (Fig. 2) and her conclusion supported the interpretation of the burial as that of an elite female (Fig. 3). This debate about biologically determined sex and socially constructed gender was vital in the second phase of gender archaeology, or the real beginning of gender archaeology, as believed by some. This development in gender archaeology emerged around 1984, upon the publication of Conkey and Spector’s paper, Archaeology and the study of Gender, in the UK and America, and was simultaneous with the emergence of the journal K.A.N.: Kvinner I arkeologi I Norge (Women in Archaeology in Norway) in Norway. It began to be recognised that although sex can be biologically determined through the analysis of skeletal remains, gender is a social construct that varies within each society as well as through time, and which can only be merely suggested by artefacts. This new understanding was heavily worked upon in the second phase, but later fiercely criticised by the third wave of feminism as ‘essentialist’. Therefore, it was merely emphasising the difference between men and women, and encouraging the traditional bipolar concept of the two genders (Arnold and Wicker 2001, 138). This could be a direct criticism of Arnold’s conclusion, because although she does challenge the traditional interpretations of gender representation in the archaeological record, she does still divide the two genders in terms of just burial goods, or more accurately, the quantity of burial goods (Arnold 1991, 372).

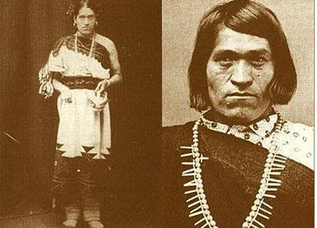

The next development in gender archaeology was closely associated with the feminist movement from the 1990’s onwards, and moves forward in the understanding that the field of gender and gender difference is more than simply a divide, but includes third, fourth and neutral genders (Figs. 4 and 5). Archaeological works began to reflect the wider social understanding that gender, like wealth, age and ethnicity, is a non-static construct which is fluid and flexible (Amundsen-Meyer et al. 2010).

The most explored area is the idea of ‘two-spirit’ individuals in Native American society (Fig. 6). Although it is the most celebrated of the third-gender roles worldwide, with 150 North American tribes mainly from the Plains recognising individuals as those of the two-spirit (Rosoe 1994, 330), it is incredibly difficult to see evidence of this in the archaeological record. However, Whelan identified a possible example of a two-spirit burial with an associated assemblage (1991). The Santee Sioux cemetery in present-day Nebraska was in use around 1830-1850 AD, with thirty-nine individuals being recovered to date. The biological sex of these individuals is divided almost equally. Whelan stressed that sex and gender were distinguished analytically, and the designation of gender categories was not prescribed on the basis of biological sex. Each of the skeletal remains were analysed independently of artefacts associated with each burial, using multivariate sexing and ageing methods where possible. Interestingly, none of the artefacts analysed indicated, or were associated with age, sex or subsistence activities, debatably suggesting that these burials were representative of symbolic status only. The gender of each individual was also analysed independent of the sexing; certain artefacts repeated in relation to a specific gender category, such as those with documented ritual associations (e.g. pipestones, mirrors, pouches) were associated with seven people. When compared with the analyses of the skeletons’ biological sex, six of these were male with only one resulting as a female. This one female was a young adult, and was buried with more varying artefacts than any other individual in the cemetery. Whelan’s concluding theory was that this could be an archaeological example of a two spirit individual – a biological female who changed her gender, achieving a respected, shamanic role in the Santee community (Renfrew and Bahn 2005, 95-108).

The development of gender archaeology has clearly progressed throughout the twentieth century in response to society’s changing attitude. Although there have been criticisms of the developments, and of the late concern within the discipline in comparison to other social sciences (Nelson 1997, 15-20, Wylie 1991), there is now a widespread and strong determination to understand the genders of past peoples, independent of biological sex. The three case studies I chose emphasise this, demonstrate how research into gender is no longer about “centralizing women and securing their presence in…research agendas and interpretations” (Sorensen 2000, 39-40). With the development of archaeological theory, for instance, Processualism, Post-Processualism and Feminism, there is now consideration of the idea of the individual or the agent. Gender archaeology now attempts to categorise less; exploring the agent and their interactions with others, and trying to understand how this, in addition to their varying social structures and ideologies, is affected and shaped (Sorensen 2000, 39-40). However, there still remains some debate as to the extent of how the topic of gender and how it is approached within archaeology has progressed. Similarly, Nelson argues that many text books on archaeology still neglect gender as an important element of the past (2006, 16), whilst Denning similarly believes that ‘gender archaeology’ has become normalised within the subject, so much so that it now remains merely as a “discrete subcategory of the discipline” and has “neutralised the power and politics of a feminist approach” (2000, 214).

Bibliography

- Amundsen-Meyer, L., Engel, N. and Pickering, S. (2010). Identity Crisis: Archaeological Perspectives on Social Identity. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Chacmool Archaeology Conference. University of Calgary: Calgary, Alberta.

- Arnold, B. (1991). ‘The Deposed Princess of Vix: The Need for an Engendered Prehistory’. In Walde, D. and Willows, N. D. (Eds.) ‘The Archaeology of Gender’, Proceedings of the Twenty-second Annual Conference of the Archaeological Association of the University of Calgary. The University of Calgary Archaeological Association 1991.

- Arnold, B. and Wicker, N. L. (2001). Gender and the Archaeology of Death. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Balme, J. and Beck, W. (Eds.) (1995). Gendered Archaeology: The Second Australian Women in Archaeology Conference. Research Papers in Archaeology and Natural History 26. Canberra, Australian National University.

- Bolger, D. (2012). A Companion to Gender Prehistory. John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester.

- Burtt, F. (1987). ‘“Man the Hunter”: bias in children’s archaeology books’. Archaeological Review from Cambridge. 6 (2): 157-174.

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble. Routledge: London.

- Claasen, C. (Ed.) (1992). Exploring Gender through Archaeology. Madison: Prehistory Press.

- Conkey, M, W. (2007). Questioning theory: is there a gender of theory in archaeology? The Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 14, 285-310.

- Englestad, E. (1991). Images of power and contradiction: feminist theory and post-processual archaeology. Antiquity. 65, 502-514.

- Englestad, E. (2007). Much more than gender. The Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 14, 217-234.

- Frink, L., Shephard, R. and Reinhardt, G. (2002). Many Faces of Gender. United States: University Press of Colorado.

- Gilchrist, R. (1999). Gender and Archaeology. Contesting the Past. Routlege: London.

- Gimbutas, M. A. (1974). The Gods and Godesses of Old Europe: 7000 to 3500 BC: Myths, Legends and Cult Images. United States: University of California Press.

- Greene, T. and Moore, K. (2010) Archaeology: An Introduction (5th Edition). United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, Inc.

- Hays-Gilpin, K. and Whitley, D. S. (1998). Reader in Gender Archaeology. London: Routledge.

- Hawkes, C. F. C. and Hawkes, J. H. (1943). Prehistoric Britain. London: Penguin Books.

- Hills, C. (2004). Newnham College, University of Cambridge: Biographies [Online]. Available at: http://www.newn.cam.ac.uk/about-newnham/college-history/biographies/cont.... (Accessed on 21/10/2014).

- Hodder, I. (1995). Theory and Practise in Archaeology. Routlege: London.

- Nelson, S. M. (2006). Handbook of Gender in Archaeology. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

- Nelson, S. M. (1997). Gender in Archaeology: Analyzing Power and Prestige. Rowman and Littefield Publishers, Inc. AltaMira Press.

- Renfrew, C. and Bahn, P. (2004). Archaeology: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

- Sabloff, J. A. and Willey, G. R. (1993). A History of American Archaeology (3rd Edition). New York: W.H. Freeman and Co.

- Sørensen, M. L. S. (2000). Gender Archaeology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Sørensen, M. L. S. (2005). ‘Feminist Archaeology’. in C. Renfrew and P. Bahn (eds) (2004) Archaeology: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

- Spindler, G.D. and Spindler, L. (1983). Anthropologists View American Culture. Department of Anthropolgy, Stanford University, California.

- Stalsberg, A. (2001). ‘Visible Women Made Invisible: Interpreting Varangian Women in Old Russia’. In Arnold, B. and Wicker, N. L. (Eds). Gender and the Archaeology of Death. New York: Altamira Press.

- Unstead, R. J. (1953). Looking at History 1: From Cavemen to Vikings. London: Black.

- Whelan, M. (1991) ‘Gender and Historical Archaeology: Eastern Dakota Patterns in the 19th Century’. Historical Archaeology. 17-32.

- Wolle, A. and Tringham, R. E. (2000). Multiple Çatalhöyüks on the World Wide Web. Catal Vol2 Reflexive Methodology 2000 Wolle/Tringham Multimedia.

- Wylie, A. (1991). ‘Gender Theory and the Archaeological Record’. In Conkey, M. W. and Gero, J. M. (Eds). Engendering Archaeology: Women and Prehistory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Figures

Figure 1: Sourced from Marija Gimbutas’ Collection, OPUS Archives and Research Centra, Santa Barbra, CA.

Figure 2: Sourced from Arnold 1991, page 361.

Figure 3: Sourced from Spindler and Spinder 1983, page 230.

Figure 4: White, R. and Bisson M. (1998). Imagerie féminine du Paléolithique : l'apport des nouvelles statuettes de Grimaldi, Gallia préhistoire. Tome 40: 95-132.

Figure 5: https://www.flickr.com/photos/catalhoyuk/15030235650/ or http://www.catalhoyuk.com/media/photography.html

Figure 6: Photographs by Zuleyka Zevallos from the article Zevallos, Z. (2013). ‘Rethinking Gender and Sexuality: Case Study of the Native American ‘Two-Spirit’ People’. Available at: http://othersociologist.com/2013/09/09/two-spirit-people/.