Introduction

The importance of Chalcatzingo as a record of human activity in the eastern Valley of Morelos, Mexico cannot be underestimated. Within this large terraced community nestled between two granodiorite hills – Cerro Delgado and Cerro Chalcatzingo – starkly juxtaposed against the surrounding agricultural lands (Fig. 1), eighty years of archaeological exploration and research has yielded significant insights into the development of complex polities during the Formative period in general, and of the rise of Chalcatzingo as a major administrative and ceremonial center in particular (Guzmán 1934, Piña Chan 1955, Cook de Leonard 1967, Gay 1972, Grove 1984, 2000). Central to these investigations has been the site’s impressive corpus of rock carvings, stelae, altars, and cup-marked stones (Grove 1968, 1987b, Grove and Angulo 1987, Lambert 2010). The purpose of this brief report is to put on record one of the many sculptural fragments from the Chalcatzingo archaeological zone (Figs. 2 and 3). At present little is known regarding its date of discovery or archaeological context and it has not been mentioned in any archaeological publications regarding the site and its monuments (Aviles 2005, Córdova Tello and Meza Rodríguez 2007, Gillespie 2008, Grove 1996, 2008, Grove and Angulo 1987). However, this enigmatic stone is worthy of note because it displays three distinct forms of modification and anthropic marking: low-relief carving, fracturing, and possibly toppling. Therefore, even though it may be difficult to establish its chronological placement in relation to the other monuments of Chalcatzingo, careful analysis of these markings and forms of modification may yield pertinent information regarding cultural practices documented at the site throughout the Formative period, especially those linked to monument mutilation (Grove 1981)

The Sculptural Fragment from Chalcatzingo

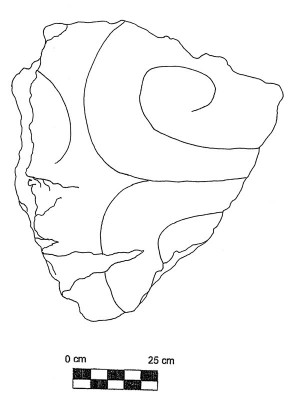

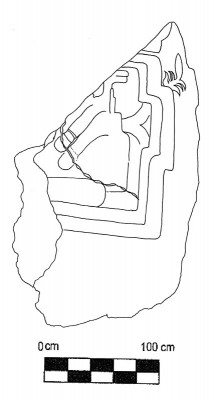

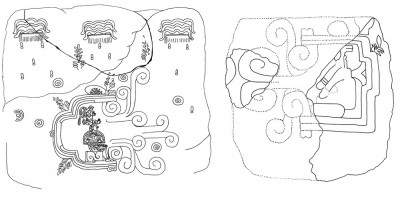

This fractured stone first came to my attention during an investigation of the rock carvings at Chalcatzingo in August 2005. Located to the immediate right of a low-relief carving known as Monument 13 (Figs. 4 and 5), it is found approximately 25 to 30 meters downhill from the Group B rock carvings on the northern talus slopes of Cerro Chalcatzingo. The sculptural fragment itself consists of a triangular rock, measuring 70.9 cm in height and 60 cm in length. It is light tan in colour and is composed of moderately coarse granodiorite (see Fig. 2). The stone is decorated with the remains of a low-relief carving representing a bifurcate scroll motif. Such scroll motifs are common in the Olmec-style rock carvings of the Cantera phase of the Middle Formative period at Chalcatzingo, c. 700-500 BC (Angulo 1987,137-138). They appear in the Group A rock carvings situated on the northwestern slopes of Cerro Chalcatzingo, most notably Monument 1 (Fig. 6). In this sculptural context, they are associated with images of clouds and rain drops as the carriers of moisture from the underworld, which is represented as zoomorphic cave openings and reptilian figures (Lambert 2015). A related set of symbols is evident in the nearby Group B rock carvings where clouds continue to be associated with rainfall but are intermixed with feline and serpent imagery (Lambert 2013, 93-94).

Given its fractured state, it is clear that this sculptural fragment was once part of a much larger composition. One possible candidate is Monument 13. Both of these damaged carvings were found in close proximity and Monument 13 appears to closely match the symbols used in Monument 1, such as the seated ruler and the quadripartite cave opening, but it is missing the cloud imagery, volutes, and bifurcate scrolls. The sculpture fragment, by contrast, consists exclusively of the remains of a bifurcate scroll. Assuming that Monument 13 was once part of a much larger rectangular slab that once stood upright (Grove and Angulo 1987,122), it is very plausible that the sculptural fragment under consideration may have been part of the damaged sections of the original monument before it was toppled (Fig. 7).

Another possibility is that it belongs to an undiscovered rock carving or sculpture situated further up the northern talus slopes of Chalcatzingo. Although less likely, this scenario remains plausible due to the periodic discovery of fractured monuments on the terraces at the base of Cerro Delgado (Gillespie 2008, 9, Fig. 2) as well as several new broken monuments near the Group B rock carvings (Grove 1996, González, Córdova, and Buitrago 2011).

Regardless of its specific origins, from these observations it is clear that any discussion of the sculptural fragment’s state of preservation and possible primary contexts must take the cultural practice of monument mutilation into account. Often linked to status competitions that may have accompanied the death of a ruler (Clark 1997, 220-222, Grove 1981, 63-65), acts of monument mutilation at Chalcatzingo appear to have involved several types of damage ranging from deliberate fracturing and breakage to toppling and decapitation. In light of these considerations, it is interesting to note that the monuments and carvings located on Terrace 6 near Cerro Delgado and on the northern talus slopes near the Group B rock carvings not only displayed the greatest degree of mutilation, especially in the form of fracturing and toppling, but were also located closest to the main areas of public interaction at the site: the central plaza and the main platform mound. As such, these broken monuments would have made pointed examples of the socio-political competitions periodically witnessed in the Middle Formative period at Chalcatzingo; after the passing of one of its rulers, new lords attempted to enhance their positions in the community through public displays, such as the erection of new sculptures and the toppling of the previous ruler’s monuments.

Conclusion

A careful examination of the iconographic details and anthropic markings of a sculptural fragment from the Central Mexican site of Chalcatzingo has allowed a number of inferences to be made regarding its probable chronological position and possible significance. Based on the stylistic affiliations of the bifurcate scroll design found on its worked surface, the sculptural fragment seems to have been originally carved sometime during the Cantera phase of the Middle Formative period (700-500 BC). The bifurcate scroll motif, along with the fractured state of the stone, also suggest that this stone was part of a much larger flat-faced sculpture that may have encompassed a larger existing carving, such as Monument 13, into the panel. If this reconstruction is correct, then the purpose of this carved panel may have been to legitimise a ruler’s right to govern through the use of underworld and fertility imagery, much like the rock carving known as Monument 1 (Lambert 2015). Like several other monuments at Chalcatzingo however, the original sculpture seems to have been destroyed as part of status competitions between lords seeking to cement their right to rule over the community.

Acknowledgments

My research at Chalcatzingo was funded through a graduate student research grant from the Anthropology Department at Brandeis University. Permission to investigate the site’s monuments and rock carvings was kindly granted by Mario Córdova Tello of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia center in Morelos (INAH Permit No. P.A. 42/05).

Bibliography

- Angulo, J. (1987). ‘The Chalcatzingo Reliefs: An Iconographic Analysis’ in Grove, D.C. (ed.): Ancient Chalcatzingo.132-158. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Aviles, M. (2000). The Archaeology of Early Formative Chalcatzingo, Morelos, México, 1995. FAMSI Grantee Report. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., http://www.famsi.org/reports/94047/index.html, accessed January 8, 2013.

- Clark, J. E. (1997). The Arts of Government in Early Mesoamerica. Annual Review of Anthropology. 26: 211-234.

- Cook de Leonard, C. (1967). ‘Sculptures and Rock Carvings at Chalcatzingo, Morelos’ in Studies in Olmec Archaeology. 57-84. Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility, No. 3. Berkeley: University of California, Department of Anthropology.

- Córdova Tello, M. and Meza Rodríguez, C. (2007). Chalcatzingo, Morelos: Un discurso sobre piedra. Arqueología Mexicana. 87: 60-65.

- Gay, C. (1972). Chalcacingo. Portland, Oregon: International Scholarly Book Services.

- Gillespie, S. D. (2008). Chalcatzingo Monument 34: A Formative Period “Southern Style” Stela in the Central Mexican Highlands. The PARI Journal. 9 (1):8-16.

- González C. O. L., Córdova T. M., and Buitrago S. G. (2011). El Monumento 41 o Triada de los Felinos. Chalcatzingo, Morelos. Arqueología Mexicana. 111: 18-23.

- Grove, D. C. (1968). Chalcatzingo, Morelos, Mexico: A Reappraisal of the Olmec Rock Carvings. American Antiquity. 33 (4): 486-491.

- Grove, D. C. (1981). ‘Olmec Monuments: Mutilation as a Clue to Meaningi in Benson, E.P. (ed.): The Olmec and Their Neighbors: Essays in Honor of Matthew W. Stirling. 48-68. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks/Trustees of Harvard University.

- Grove, D. C. (1984). Chalcatzingo: Excavations on the Olmec Frontier. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Grove, D. C. (1987). ‘Miscellaneous Bedrock and Boulder Carvings’ in Grove, D.C. (Ed.): Ancient Chalcatzingo. 159-170. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Grove, D. C. (1996). ‘Archaeological Contexts of Olmec Art Outside of the Gulf Coast’ in Benson, E. P. and de la Fuente, B. (Eds.): Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. 105-118. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art / Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Grove, D. C. (2000). ‘Faces of the Earth at Chalcatzingo, Mexico’. In Clark, J. E. and Pye, M. E. (Eds.): Olmec Art and Archaeology. 276-295. Studies in the History of Art, Volume 58. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Grove, D. C. (2008). Chalcatzingo: A Brief Introduction. The PARI Journal. 9 (1): 1-7.

- Grove, D. C. and Angulo, J. (1987). ‘A Catalog and Description of Chalcatzingo’s Monuments’ in Grove, D.C. (Ed.): Ancient Chalcatzingo. 114-131. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Guzmán, E. (1934). Los Relieves de las Rocas del Cerro de la Cantera, Jonacatepec, Morelos. Anales del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnografía. 5 (1): 237-251.

- Lambert, A. (2010). The Cupulate Complexes of Chalcatzingo, Morelos: A Preliminary Investigation. American Indian Rock Art. 36: 183-192.

- Lambert, A. (2013). Olmec Ferox: Ritual Human Sacrifice in the Rock Art of Chalcatzingo, Morelos. Adoranten. 2012: 93-102.

- Lambert, A. (2015). Rock Art and Rituals of Rulership at Chalcatzingo, Morelos, Mexico. American Indian Rock Art. 41: In Press.

- Piña Chan, R. (1955). Chalcatzingo, Morelos. Informes Núm. 4. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.