For three days from Monday 14th May to Wednesday 16th May, the Department of Archaeology and Conservation at Cardiff University was home to the 'Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science' conference. As explained in the welcome speech by Dr. Penny Bickle, one of the organisers of the event, its intended purpose was to bring together researchers in scientific and interpretative archaeology in an attempt for both sides to recognise that their interests in the early agricultural populations, societies and environments of Neolithic Europe are in fact shared and should be enhanced by greater collaboration in research.

The following review will be the reflections of perhaps the youngest person who attended the conference (a second year bioarchaeology undergraduate student at the University of York). Whether you think the opinions below are naive or refreshingly different, your comments and own opinions will be very gratefully received by The Post Hole.

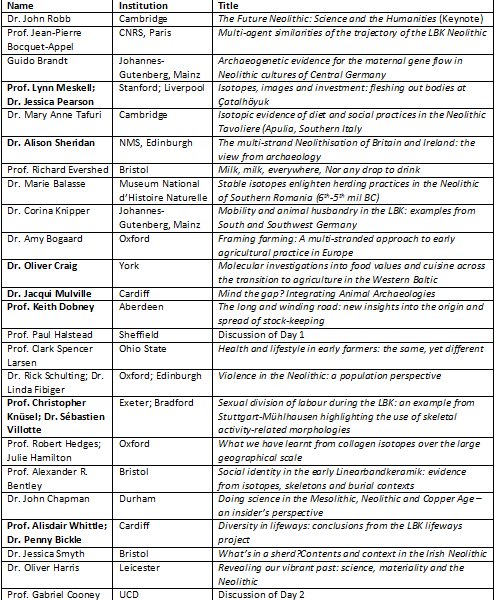

A packed schedule comprising of a wide range of speaking archaeologists and archaeological scientists ensured that the aim of bringing together the broad spectrum of fields studying the Neolithic was achieved. Above is full list of all the participants. Unfortunately there is only enough space to discuss seven of the presentations, which are highlighted in the list.

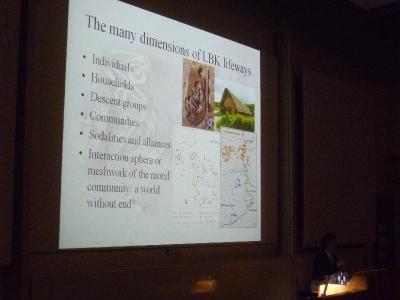

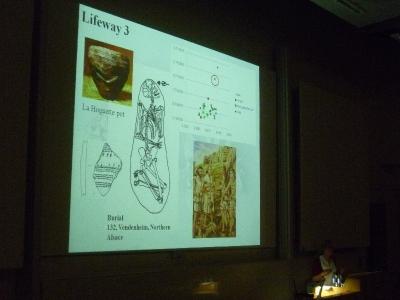

Prof. Alisdair Whittle and Dr. Penny Bickle - Diversity in lifeways: conclusions from the LBK lifeways project

Perhaps the most optimistic presentation was the one given by the hosts of the conference — Prof. Alisdair Whittle and Dr. Penny Bickle. Outlining their recent work on the Cardiff-Oxford-Durham research project, 'The first farmers of Central Europe: diversity in LBK lifeways', Bickle and Whittle demonstrated the apparent ease of a collaborative project between archaeology and science to reveal aspects of diet and mobility in LBK societies. Their consideration of the differences in these relationships with varying scales of analysis, from the individual — through stable isotope and mortuary analysis of human remains — to wider society — through the comparison of different settlements and cemeteries in regional and wider settings — was rather unsettling. How was this so easy?

The answer seems to be the close collaboration and mutual respect of different practical and theoretical approaches to interpreting the Neolithic, rather than using the period (as so often before) as a battleground for science and archaeology. The project has been a success because it has stepped beyond the carnage of the battlefield and looked meaningfully at the subject of archaeology — discerning the scale at which the past individual viewed the world, in which he or she lived and died (Whittle & Bickle, 2012).

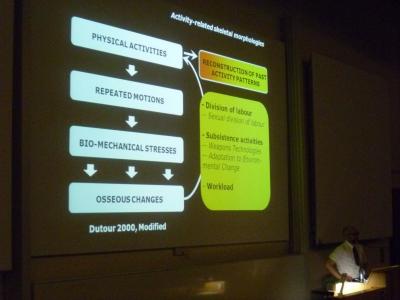

Prof. Christopher Knüsel and Dr. Sébastien Villotte - Sexual division of labour during the LBK: an example from Stuttgart-Mühlhausen highlighting the use of skeletal activity-related morphologies

Prof. Christopher Knüsel (Exeter) and Dr. Sébastien Villotte's (Bradford) paper showed similar promise in directly addressing a rarely studied aspect of Neolithic life; in this case, the sexual division of labour in early farming communities. They convincingly demonstrated that by analysing the lesions of upper limb tendons, a very clear picture of differential motor actions between males and females from Stuttgart-Mühlhausen can be elucidated, and more importantly, the use of a very specialised line of enquiry can in some cases be of equal benefit to broader discussions of life in the Neolithic as studies incorporating many fields of study, so long as the broader implications of research are properly considered.

Knüsel and Villotte's research offers exciting prospects for understanding the stratification of labour within populations, and should be used more widely in the studies of other communities and alternative divisions, such as inferred age and mortuary prestige of individuals to open up further questions about lifestyle across different sectors of society (Knüsel & Villotte, 2012).

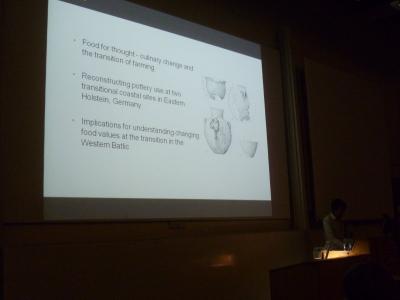

Dr. Oliver Craig - Molecular investigations into food values and cuisine across the transition to agriculture in the Western Baltic

As one may expect, the Early Farmers conference was mostly focused on diet and subsistence in the Neolithic. Dr. Oliver Craig's (York) paper on organic residue analysis of Ertebølle pottery from northern Germany offered a unique opportunity to focus more specifically on cuisine. The social, cultural and sensual processes behind what people eat and how they eat is something that is sadly overlooked in archaeology. Although, as acknowledged by some of the audience, organic residue analysis of pottery cannot inform understanding of broad diet and subsistence of individuals — as discerned from direct stable isotope analysis of bones — or of whole populations, due to the obvious reasons that pots are not involved in all preparation and consumption of food by all people, it can equally be argued that other analyses of diet and subsistence do not normally include cultural and personal agencies influencing people's interaction with food, or that not all food was treated as food (for example, oils from fish used as illuminants in vessels).

The nuanced changes in the uses of pots across the Mesolithic-Neolithic divide determined by organic residue analysis can offer unique suggestions of the influences on and results of changing economies and transition to agriculture within cultures (Craig, 2012).

Dr. Jacqui Mulville - Mind the gap? Integrating Animal Archaeologies

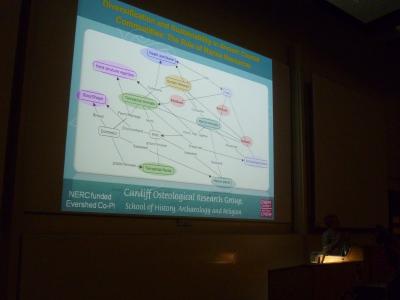

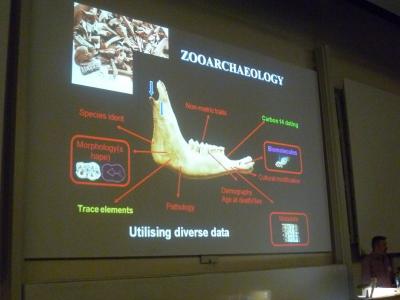

Whilst the value of using specific lines of inquiry to address specific, often overlooked questions about the past is undoubtedly beneficial to archaeology, combining these should be viewed similarly, particularly if it helps address complex interactions between different aspects and influences of lifestyle and society. This is excellently illustrated in Dr. Jacqui Mulville's presentation (see photograph below).

Like Prof. Whittle's observation that different scales of analysis can produce different focuses in results, Dr. Mulville (Cardiff) identified that overlapping methodologies did the same thing. This, it could be argued, is a positive phenomenon that can be utilised to provide more comprehensive perspectives of the past. It was enlightening to see Mulville's demonstration of the extent zooarchaeological and stable isotope evidence can sometimes sharply contrast. Looking at the Atlantic island sites that were studied in her and Prof. Richard Evershed's Diversity and Sustainability in Marine Resources project, she demonstrated that provided there is sufficient relevantly overlapping data — in this case, zooarchaeological, stable isotope and organic residue — they should be combined to provide broader perspectives on agricultural practices (Mulville, 2012).

Prof. Keith Dobney - The long and winding road: new insights into the origin and spread of stock-keeping

Another presentation which featured the combination of analytical techniques was Prof. Keith Dobney's (Aberdeen) on using osteological and aDNA evidence to trace the westward movement of domesticated pigs through Europe from the Near East and the subsequent separate domestication of European wild boar. The geographic and chronological sequence of the spread of the 'Neolithic Package' of domesticated animals and crops, among other Neolithic innovations, remains to this day one of the greatest mysteries in archaeology, despite it being one of the most intensively studied processes in archaeology.

The coupling of osteology and DNA analysis to attempt to clarify this complex set of changes to subsistence in Europe is a further example of the exciting progress being made in integrating traditionally disparate lines of inquiry to address a common research question. The sequence by which domesticated pigs of different geographic origins replaced one another and the confirmation of multiple areas involved in substantial regionalised domestication of animals should offer new opportunities for archaeologists and scientists to consider and reconsider the geographical and cultural spheres of agricultural spread and change in Neolithic Europe (Dobney, 2012).

Dr. Alison Sheridan - The multi-strand Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland: the view from archaeology

It was clear that the views of one speaker members of the audience either appreciated or (a little unfairly) scorned. Dr. Alison Sheridan (NMS, Edinburgh) very admirably used her presentation to call on archaeology and science to work more collaboratively in order to approach the past more holistically. While this message should be encouraged by the academic community, the apparent negative reception the presentation received from some people was not associated with this call to arms — all of the speakers made clear their interest in multidisciplinary research — but because (arguably) Dr. Sheridan did not clearly demonstrate how the many strands of her research were connected.

This is not to say that her study of the adoption, spread and consequences of jade axe material culture on societies is not of worth or potential to archaeology; rather, the work of Project JADE should be better demonstrated as being cohesive towards addressing the many aspects of the material culture, its geographic spread and cultural impact in Europe. One example of this was the use of the jade axe deposited beside the Sweet Tract in Somerset, a static entity, in the rhetoric of other non-static entities of jade axe adoption in mainland Europe. Archaeological data is finite and so such uses of static entities in the interpretation of non-static changes, as above, should be accepted, so long as they are rigorously justified through alternative information, or explicitly noted consideration of the analytical implications — neither of which were fully achieved by Sheridan in her presentation (Sheridan, 2012).

One positive consequence of this was the discussion amongst the audience of whether the main obstacle to studying the past is a general lack of data in archaeology or the reticence of some researchers to accept that lack of data and make the most of it. This question will be returned to at the end of the review.

Prof. Lynn Meskell and Dr. Jessica Pearson - Isotopes, images and investment: fleshing out bodies at Çatalhöyük

Prof. Lynn Meskell (Stanford) and Dr. Jessica Pearson's (Liverpool) research on combining two very different forms of evidence to build credible alternative interpretations of deeply psychological and socio-cultural views of bodily image in the past is perhaps one of the most exciting current achievements in archaeology. Rarely does research simultaneously incorporate multiple methodologies — in this case stable isotope analysis of human remains and typological study of mortuary figurines — and succeed in delivering a succinct, comprehensive narrative of the less discernible levels of social and psychological reasoning of individuals behind the material culture they choose, or are chosen by others, to be associated with.

In what was a fascinating presentation that challenged the traditional singular approaches of archaeology and science towards the study of mortuary treatment and human biographies, Meskell and Pearson demonstrated that their combination of techniques with a broader consideration of the built environment of Çatalhöyük, particularly of the numerous wall murals around the site, suggests that the figurines always associated with the Mother Venus and fertility, due to stereotypical associations with their bodily form, may have actually served as symbols of prosperity through the plentiful availability of food. They observe that the figurines are more indicative of obesity and flesh, and that this theme occurs throughout the city in the storage areas used to contain excess food, the abundance of hunted animals represented in wall murals, the post-mortuary treatment of flesh of the deceased, and the stable isotope data of skeletal remains.

The apparent similarity between the analyses of these very different indicators makes Meskell and Pearson's suggestion of flesh and obesity serving as a symbol of an individual or a group's prosperity all the more compelling. Furthermore, this presentation was beneficial in highlighting that different kinds of data can indeed be combined to offer tentative suggestions of lifestyle in the Neolithic. Perhaps this was made possible by the considerable amount of archaeology that is preserved at Çatalhöyük, and in other cases, such an overlap of different lines of inquiry would not be possible; but it is certainly advisable that this is tested in all manner of other archaeological contexts, as it may prove highly valuable to looking at the past. (Meskell & Pearson, 2012).

As demonstrated through these seven presentations, the analogy of science and archaeology first suggested in this review should be reconsidered. The conference was a huge success for encouraging a vast array of researchers to share and discuss their studies of Neolithic Europe. It is encouraging to see many of the projects presented making use of linking multiple specialism's and that archaeologists and scientists — however they identify themselves — are starting to recognise that working together is essential if more holistic perspectives of the past are to be formed.

So the conference was a success, different methodologies are starting to be combined, but archaeology still has a long way to go! The remaining, and perhaps highest hurdle between archaeology and science is the way data that these methodologies produce is interpreted. The sooner we all stop forever whining that "we need more data" and arguing over interpretative paradigms for the sake of arguing, but instead recognise that we are all people with an interest in the past, the sooner we will be able to make the most of the data we have and work effectively together to acquire more.

Thanks should go to Dr. Penny Bickle and Prof. Alisdair Whittle for organising a superb conference, and to the speakers in the photographs for agreeing to them being included in this review. Thank you also to Marc Renshaw for producing the illustration at the start of this review.

Bibliography

- Craig, O. (2012). Molecular investigations into food values and cuisine across the transition to agriculture in the Western Baltic. [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 14 May 2012.

- Dobney, K. (2012). The long and winding road: new insights into the origin and spread of stock-keeping. [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 14 May 2012.

- Knüsel, C. & Villotte, S. (2012). Sexual division of labour during the LBK: an example from Stuttgart-Mühlhausen highlighting the use of skeletal activity-related morphologies. [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 15 May 2012.

- Meskell, L. & Pearson, J. (2012). Isotopes, images and investment: fleshing out bodies at Çatalhöyük [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 14 May 2012.

- Mulville, J. (2012). Mind the gap? Integrating Animal Archaeologies. [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 14 May 2012.

- Sheridan, A. (2012). The multi-strand Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland: the view from archaeology. [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 14 May 2012.

- Whittle, A. & Bickle, P. (2012). Diversity in lifeways: conclusions from the LBK lifeways project. [Early Farmers: The View from Archaeology and Science] Department of Archaeology and Conservation, Cardiff University. 15 May 2012.