Professor Milner is a Mesolithic Archaeologist based at the University of York. We interviewed her earlier this year to find out about the home of Britain’s oldest known ‘house’, Star Carr; a site she has excavated at for over 15 years...

What first interested you in becoming an archaeologist and why did you decide to specialise in Mesolithic archaeology?

I was always interested in archaeology as a child, and one of the things that really inspired me was when I went to the Jorvik Centre when I was about eight — there was a wall of pottery and I thought that it was really amazing that you were actually allowed to touch it... later, when I was sixteen I went on a dig with Dominic Powlesland as part of the Duke of Edinburgh’s residential scheme - I went for five days and ended up spending six weeks there. So that’s what got me into archaeology. What got me into the Mesolithic was being taught by Roger Jacobi at Nottingham University who was very inspiring and knew so much about the period. I was particularly interested in Star Carr because it was not far from where I lived.

Do you think that the Mesolithic period is overshadowed by its neighbours, the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic, and if so, what is your opinion about this?

I think it has and I think the reasons for that are people have tended to focus on flint and not thought how to make the period particularly interesting. It also lacks the cave art and monuments you get in the other two periods. But everything is changing and a lot of people are interested in the Mesolithic now. For instance, in Europe at the last Mesolithic conference there were over 400 people, all working on things that can make it more interesting, like ritual, burial, subsistence and consumption practices.

As you say, there does seem to be a growing awareness of the Mesolithic in recent years, and Star Carr has certainly played a central role in this. What do you think are the most effective ways of engaging the public with this part of the past?

For the Star Carr Project I’ve given a lot of talks to local societies in the last few years and people seem to be really engaged and interested in it; they haven’t really heard much about it before. But what we’re very aware of is that we’re not really reaching groups other than local societies who may already have an interest in history or the local environment, and what we’re really planning is engaging children in the period; particularly because in Denmark, the Mesolithic is seen as their ‘Golden Age’ and they teach it in schools and the children play bows and arrows and Stone Age hunters. We’ve got a project at the moment being developed by Emily Hellewell with a number of students, trying to work out activities which can be used by the Young Archaeologist’s Club, but we’re always looking for new ideas so if anybody wants to get involved or share their ideas, we’re always open to suggestions.

Your discovery two years ago of possibly the oldest ‘house’ and evidence of carpentry in Britain has since attracted much greater coverage of Star Carr in the media. Do you think there have been any problems with the way that the press has presented Star Carr or the Mesolithic?

Well the press came out with some funny ideas — they talked about the timber platform as the earliest timber decking, and one newspaper referred to the structure as the “crappiest house in Britain”, which was quite rude! So there are things like that, but actually I don’t really have any problems with the way they portrayed it because they did a great service by getting lots of people interested, and it did go world-wide in terms of coverage. I think you have to accept that if you’re going to do press releases, people are sometimes going to write things like that but you also have to think of ways in which you’ll appeal to a wide audience.

You’re not the first person to have excavated at Star Carr. How has investigation of the site developed since it was discovered in 1947 and how and when did you become involved with it?

Well, the other major phase after Clark, was in 1985 — most people will know about it from the book by Paul Mellars and Petra Dark (1998) — but what they probably don’t know is that it was Paul Lane, here at York, who excavated it with Tim Schadla-Hall; and it was Paul Lane who realised that the wood was actually worked timber and so very important. I got involved because in 1996 I started working with the Vale of Pickering Research Trust, and Tim Schadla-Hall, and (together with Chantal Conneller and Barry Taylor) we discussed doing some more excavations at Star Carr because we thought there might be problems with deterioration.

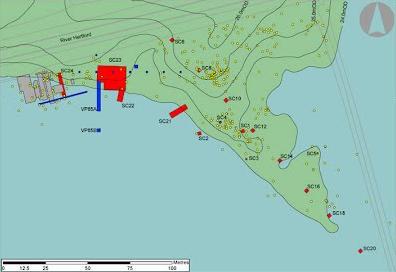

One of the major developments in our understanding of the site is of its size. Grahame Clark stopped excavating after three years in 1951 because he believed he found the whole site. What has been found that makes you think the site is more complex than originally believed?

I think the key thing is we‘ve broadened our area of survey; we did fieldwalking first of all, and then a lot of test pitting over the whole peninsula and found that there’s huge quantities of flint all over that whole area. We now think that Grahame Clark only excavated less than a 5th of what the overall area probably is, and may well be underestimating it. I think the reason why he got it wrong, (but you can completely understand his logic), is because he excavated an area and he showed there was a large concentration of flints in the middle that petered out around the edges, so it really did look like it was a total excavation. Also, he was comparing it with other sites in Europe and saying that all these other sites in Germany and Denmark were about that size and so it was seen to be typical of a Mesolithic site. We think the trouble is it’s been a self-fulfilling prophecy so we keep thinking Mesolithic sites will be small when they’re probably much larger, and it’s actually because of archaeological methods and our preconceptions that we still keep talking about small sites all the time — we are about to publish this theory in the next issue of Antiquity.

As well as attracting a lot of attention from the media, Star Carr has interested a lot of academics. How has the interpretation of what life might have been like at Star Carr changed over the last sixty years and is there currently any consensus on perhaps the most contentious question, that of the seasonality of its use?

Well that’s right. There have been so many different interpretations and I think even the three of us who have directed it (Chantal Conneller, Barry Taylor and I) probably have different views about how it was used. The main problem is that we’re dealing with one piece of the jigsaw here. We’ve dug a very small amount, and all these past interpretations have been based on that small area of excavation done by Clark. We also have another interesting fact in that we know Clark threw back into the backfill quite a lot of bone that he couldn’t identify; so when we dug in 2010, there were a large number of rib bones in the backfill. So the samples that are in the Natural History Museum are very biased samples that don’t really reflect what was there, never mind the whole site. We won’t really get a better picture until we dig more.

In terms of the seasonality, I also think that it’s almost a question that we can’t answer because it’s too complicated a site.

Grahame Clark was famous in archaeology for advocating that archaeologists should look at the environmental context of a site, rather than just its settlement or worked objects? How important do you think his views were in contributing towards the way archaeologists look at the past today?

Well to be honest, I think Grahame Clark is the founding father of Mesolithic Archaeology in this country. It was his way of doing things, considering the environment as well as the artefacts that really changed the way people studied the Mesolithic. We would barely know anything about the Mesolithic had he not encouraged other people to study it. It’s quite an interesting question - what would have happened had Grahame Clark not studied the Mesolithic. There was no one else really doing it at the time, and there were people like Gordon Childe who were quite disparaging about the Mesolithic.

Do you think what Clark found at Star Carr was important in this change in way that archaeology looks at the past?

That’s actually a difficult question to answer. What I do think is that what he found prompted people to try to find other Mesolithic sites like Star Carr.

As you say, Star Carr does seem to hold a very special place in Mesolithic Britain. What do you think are the reasons that Star Carr is so special and unique? Is it the environmental preservation or just the way it has been looked at compared to other places..?

Well my feeling is that it’s probably the artefacts because when you start counting the number of barbed points found there compared to other places, or the head dresses or beads... no one has found anything else like it which is why I think the artefacts are the number one factor. But I think there are other things as well, like the environmental context, which make it very important too; and the fact that he published it very quickly as a monograph.

Congratulations on securing £1.23 million funding from the European Research Council in January to continue looking at Star Carr. What are the reasons for you receiving this funding and what will it enable you to do?

Thank you, yes it’s fantastic! It basically funds a group of scientists to do further cutting-edge scientific research on finds and to do three or four more seasons of excavation. We have nearly twenty specialists, based both here in York and elsewhere who are leading experts in the country. So the money goes towards those people working on the Project and also the costs of doing scientific analyses.

What are the main things you’re hoping to achieve by returning to Star Carr?

One of our big things is to uncover the whole of the platform before it deteriorates for good, because we don’t really understand how it was constructed, what it was used for, or why it seems to stretch across such a large area of the lake. It is the earliest known evidence for carpentry in Europe so we need a better understanding. We also want to look at the dryland part of the site; we want to know whether there are more structures. We also want to apply forensic methods to look at how tools were used, and we’ve got geochemists involved to look at whether we can identify areas which may tell us about different kinds of activities that took place. So, we’re basically trying to get a better picture of how people were living, and the spatial arrangement of their activities.

Is another reason for you returning to Star Carr because of the ongoing deterioration of organic remains at the site?

The deterioration is one of the things that has helped us get the funding, because if we don’t go back within the next five to ten years the site just won’t be there anymore, and there’s still so much more to learn from it. First of all, we had to prove to English Heritage and other stake holders that the site is badly deteriorating — we’ve got two papers in the Journal of Archaeological Science which do that; and then we had to prove that there were still questions worth asking.

It seems odd that after thousands of years of brilliant preservation, many of the organic remains at Star Carr are suddenly deteriorating. Have you identified what it is that is causing such serious deterioration of organic remains at the site? How common is this at other sites?

It seems to be connected with drainage and because the drains take the water out of the land, the peat begins to shrink, oxidise and dry out; the water table gets lower and lower, so that means more oxygen gets into the sediments. It then creates chemical reactions, particularly with the sulphur in the sediments, and basically ends up creating sulphuric acid.

The sulphuric acid then eats away all the bone and antler. We have a PhD student at the moment, Kirsty High, who is doing more research on this because it’s really quite complex. There are all sorts of other things at work as well, and one of the things we’re really concerned about is bacteria in the deposits too, because it’s bacteria that will eat away the wood.

In terms of other sites, I was in Germany a few weeks ago talking to colleagues from right across Europe and it seems that many of the bogs sites there are suffering in a similar way.

How does Star Carr link with your other work on the Mesolithic, and with other sites of the same age?

Well my other work on the Mesolithic focuses more on coastal sites and the later part of the Mesolithic, particularly shell middens.

In terms of other sites of the same age, what we are interested in doing is to put Star Carr in a wider context and work with colleagues in Europe. We’ve just set up a Stone Age Bog group made up of people right across Europe all dealing with similar kinds of issues and questions. Some of them have really amazing bog sites.

Do you currently have any idea of the longer term future of Star Carr and what will happen there?

No, not really. We finish in five years time on our project. Probably, anything that’s left there, if it’s on the dryland part of the site, will have to stay in a management agreement with English Heritage to be protected in that way; if anything is in the wetland parts, it will probably just deteriorate and there’s nothing anyone can really do about that. So the key thing about Star Carr is that we should learn lessons from it for other sites, but the scary thing is just how many sites might be out there that are deteriorating and are unknown to us.

Star Carr currently takes up a lot of your time. Will it seem odd one day moving on from the site to focus on other projects?

I think once it’s finished I will probably continue working on other wetland sites in the area — some of the others around the lake, because there’s so much work to be done; but maybe I’ll move on to other wetland sites in other places; or maybe I’ll just move on to a completely different area of the Mesolithic! I think wetland sites are really important because they provide extra detail that other sites without that organic preservation don’t.

Professor Milner and the Star Carr Project team have just published a booklet, ‘The Story of Star Carr’, on the history of investigations at Star Carr and what they have learnt from the site. Copies cost only £2.50 each. Information on how to order a copy is available via their website.

Recommended reading

- Boreham, S., Conneller, C., Milner, N., Needham, A., Boreham, J. and Rolfe, C.J. (2011) ‘Geochemical indicators of preservation status and site deterioration at Star Carr’. Journal of Archaeological Science 38 (10), 2833-2857

- Clark, J. (1954) Excavations at Star Carr: An Early Mesolithic site at Seamer near Scarborough, Yorkshire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Mellars, P. and Dark, P. (1998) Star Carr in Context: new archaeological and palaeoecological investigations at the early Mesolithic site of Star Carr, North Yorkshire. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological research

- Milner, N., Conneller, C., Taylor, B., Koon, H., Penkman, K., Elliott, B., Panter, I. and Taylor, M. (2011) ‘From Riches to Rags: Organic Deterioration at Star Carr’. Journal of Archaeological Science 38 (10), 2818-2832

The Star Carr Project website: http://www.starcarr.com/

The Stone Age Bog Group website: https://sites.google.com/site/stoneagebogs/home