My name is Flo Laino, a third year BA Historical Archaeology undergraduate. Whilst undertaking a Visual Media module for my degree, I won a competition held by York Castle Museum to design and curate features of its new toy exhibition, as part of a competition hosted by the North Yorkshire Business Education Partnership (NYBEP) in collaboration with York Museums Trust.

The winning submission (now live!) is a teddy bear hunt for children, in which kids follow a pawprint trail to find hidden letters attached to toys in each display (Figures 1-2). The children are given the outline of the toy as a clue, shown on colourful plaques on the side of displays, which also reveal interesting historical facts about each toy. Once all the letters have been found and written down on the handy bookmark provided, they spell out the hiding place of the Castle Museum bear, a lost teddy from the First World War era.

Indeed, the whole toy exhibition is now a joy to walk through, and if I may say so myself, a gem in the social history collection of the Castle Museum. Previously, it was essentially a long and dreary narrow corridor of small cabinets (often too high for some children) filled with a mishmash of toy-curiosities (Figure 3). Since it’s reopening in January, the gallery truly does now live up to its namesake as a playful and lively toy exhibition. Located in the spacious west-wing of the Museum, the exhibition is bright and colourful, with many interactive opportunities, including quizzes, a studio area to handle artefacts and hold activities for children, a working version of pong, and of course the bear trail (Figure 4).

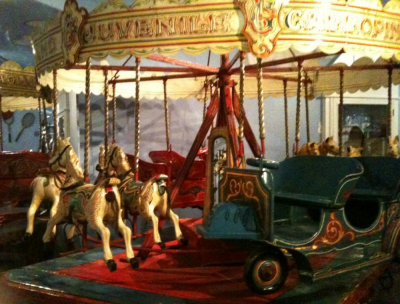

Of archaeological note are toys such as a 1950s children’s Cadillac car, and a delicate life-size working Victorian carousel (Figure 5), as well as more provocative features such as the ‘That’s His/That’s Hers’ display which seeks to engage visitors thoughtfully about gender stereotyping.

I came to enter the competition in quite a roundabout way. However, the primary reason was as a direct result of my module on Visual Media in Archaeology, taught by Dr. Sara Perry. The module explored the ways in which visual media are inextricably implicated in the construction and reproduction of academic and popular knowledge of the past, and the subjectivity of that knowledge. This issue is of acute concern to the archaeological discipline, as one which fundamentally relies on visual methods; practically, in the processing and rationalising of historical material, but also as a discursive ‘visualising’ method, to enable our theoretical interpretations.

The main project of the module was to design a blog through which to curate an object or collection of objects of our choosing. This was done to evaluate the blog format as a potential alternative to the traditional museum environment, which is well acknowledged in scholarly discourse as a highly problematic arena for the presentation of historical ideas.

I chose the subject of toys as the focus of my blog curation (http://acuriositycomplex.blogspot.co.uk/), firstly, because as a volunteer at the Castle Museum I thought it would be brilliant to capitalise on the access I had in order to provide the blog with examples from a real life case study; secondly, as I thought the nature of toys, having both play and pedagogic functions, was an interesting subject in the study of visual media.

To expand on this last point, I was keen to explore how historical representations are simplified for children, through stereotypes and cartoon toy-representations, to aid understanding, and then retained in adulthood perception.

The fact that the competition came about seemed like a neat way of tying all my ideas together in one endeavour that would provide the perfect opportunity to explore the difficulties in curation as a whole, and moreover give me a readable platform for the blog (Figure 6) that I could use to prop up my lagging page views.

The brief for the competition was to design a feature for the new Toy Gallery, to enhance the exhibition. A budget of £2,000 was given, within which all costs had to be detailed and submitted. Finally, the idea had to be pitched in a 15-minute presentation, followed by a question and answer session chaired by the Museum’s curators and judges, Head Curator, Alison Barnes and the Director of Knowledge and Learning, Martin Watts.

I decided to frame the blog around the themes in the Visual Media module and with a view to engaging the reader in a conversation of how to develop an idea that balanced both the practical museum issues and academic representational concerns.

Those well-versed in museum critique will be familiar with the arguments about how well placed the museum is as a method of archaeological dissemination, given its multiple interests as both a caretaker and business. More and more, museums have to rely on the pulling power of the family audience, which has moved many scholars to allegations of ‘dumbing-down’ and over-emphasis on experience-driven displays that solely treat historical artefacts as mere attractions.

Indeed such arguments could be seen as endemic in the Castle Museum’s display. The Castle Museum is a very family-oriented museum. Frequently employed is a contemporary set-up of a particular context as the backdrop for a display, in which artefacts are often left to testify for their own historical value, supported by little detailed information. The ultimate example to be found at the museum is the large-scale Victorian Street, ‘Kirkgate’; it works best in this instance, using a task force of knowledgeable employees and volunteers dressed in costume to enliven and animate the past-scape in a way that confronts the visitor in a memorable way and tailors the learning experience.

With a recent £1.5 million grant awarded to York Museums Trust by the Historic Lottery Fund, the Castle Museum is planning a series of renovations which lean towards this immersive, experiential style of presentation.

In considering its other, unanimated exhibitions, where artefacts are presented in a more simple nostalgic style, it might be fair to level the more severe criticisms that are often given by museum scholars, as a ‘cop out’ in attempting any ambitious academic ideas. It became apparent that the question I had to answer through the blog project would have to handle this issue directly: how to balance the museum’s business interests of appealing to families, in a way that does not diminish the historical integrity of the artefacts.

Unfortunately, as the actual designing process took-over, my blog did become somewhat sidelined. Certainly it was not particularly successful in prompting a reaction from desired commenters, as I had intended. Regardless, the project that became the Castle Museum exhibit was still an interesting practice of the interplay between academic idealism and practical situations.

Ultimately, in developing a ‘winning’ submission, I had to be concerned with what ideas would be most desirable to the Castle Museum as an employer – which was in the end, very distinctly, that the exhibition had to be fun and enjoyable for children. My research took me through a variety of ideas, looking at cool hi-tech features, like interactive ‘smart’ materials and lighting, mobile media and short films that could be selected by the user from a remote tablet, and then projected onto a large screen.

However, after many calls to graphic design and installation companies, I quickly realised that anything that could be achieved within the given £2,000 limit would be fairly basic. My studies also led me to question the technology factor as a useful way of making curation subjects interesting. In fact, such uses of technology is often criticised in journals as having too short-term a life span, or being too gimmicky and distracting from the overall point of the exhibition.

In the end, I felt a trail that used the historical artefacts was the best option. Whilst not being the most novel or innovative idea, I felt that if done correctly it would serve as a perfect marriage of the academic and practical factors I sought to negotiate. It didn’t compromise the integrity of the display; it prompted children to look beyond a basic, passive viewing of the materials in a fun way, and through its completion could impart historical knowledge that would constitute a valuable learning experience.

At the time, I was worried that the judges would find this idea boring, or too simplistic, but needless to say I should not have! Since winning the competition, the whole experience has been wonderful, with the judges whole-heartedly endorsing my ideas; my involvement was sought throughout the process to its end.

Of course, with any project there were things that had to be reworked. A strict limit of 20 words per plaque was detailed, which quashed my hopes of using the plaques of the word hunt to tell the unique histories of the specific chosen toys. Another idea was the trail should follow some kind of chronological theme, highlighting key events in British History that the toys could demonstrate, which emphasised them as historically significant to children. Initial ideas included a limited edition Golden Coach from the time of the Queen’s coronation in 1953, using Subbuteo players to highlight England’s Football World Cup victory in 1966 and cash registers to illustrate decimalisation in 1971.

Again though, practical issues meant I had to sacrifice this idea. One constraint given the tight budget the curators had to deal with was to try to maximise on pre-existing display material of the previous exhibition (The History of Cleaning Materials). In particular, the Museum had displays in place that featured heavy equipment such as baths and cooking ranges which were too expensive to remove so they were incorporated into the display cases. The downfall of my time-line idea was that a 1950s living room set-up was installed at the very start of the exhibition to display 1950s toys. Had I gone ahead with the timeline idea, it would have meant that the whole of the trail would be squashed into 50 years of British history, which I did not think was adequate in any way. In the end, we opted for more simplistic, general history facts related to the toys to be used, which on reflection was probably the most likely limit of a child’s attention.

On the day of the opening, I cannot convey how rewarding it was to see children actively seeking the trail, trying to find the letters, and running up to their teachers to tell them where they found the bear (Figure 7). In this regard, I am immensely proud at what was achieved. Whilst it might not be considered as anything academically successful as we would discuss in our seminars, it is a lesson that all too often we can get bogged down in our academic critique and get distracted from what the most important point of it all is.

Since taking my Visual Media module, and in light of this experience, my opinion has definitely altered from one of harsh critique, to immense respect for the curators of smaller, regional museums that are actually on the frontline of the heritage industry, whose purpose is to work within the community to engage local people with history and heritage.

Regardless of how historically informative the exhibition is, I argue that the method the Castle Museum employs is not a simplification of any kind to be scoffed at by critics, but rather an approach which presents the material in an imaginative and engaging way. It succeeds far better in capturing its primary audience (children), and immersing them in the subject of childhood and history.

Further information

Follow the North Yorkshire Business Education Partnership (www.nypeg.org.uk) for information on more opportunities like this one. The NYBEP is a company dedicated to liaising with businesses to empower students and young people to gain valuable experiences in the professions they hope to pursue. The competition I took part in was one of many on that day hosted by a range of employers.

Visit http://www.yorkcastlemuseum.org.uk/Page/Index.aspx to find out more about the toy exhibition and

http://www.yorkcastlemuseum.org.uk/Page/GetInvolved.aspx to volunteer at the York Castle Museum.