Christopher Howse (2009) described The Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) as "a real museum". The museum differs to numerous contemporary and architecturally Victorian museums which have been modernised. This accounts for museums such as The British Museum and The Victoria and Albert Museum, both of which are situated in London and are renowned for reinventing their museums’ position in the popular tourist industry. However, the idea of what constitutes as "a museum" varies greatly and is also dependent on individual members of the public and what they wish to gain from their time at the museum. The PRM has not dramatically changed over time, however, it has expanded to an extent, and since entering the computer age in 1986 (University of Oxford, n.d.), it has become a very desirable centre for learning. By analysing the PRM's approach to ethics, the types of display it incorporates, the text and labels used, the progression of Cultural Anthropology and how it could be adapted further, I hope to distinguish whether the PRM's appeal as "a museum of museums" is outdated or not.

The construction of the museum building began in 1885 and finished in late 1886. The building's architecture was pioneering at the time, especially the cast iron work, which bears resemblance to railway stations such as King's Cross Station in London (1852). Even today, the Victorian architecture, dominant central totem pole and dark-coated cases juxtaposed with coloured spotlights is aesthetically pleasing and creates an exquisite atmosphere. During the years of its existence, the museum's collection has increased considerably from approximately 20,000 specimens to over half a million including objects, photographs and manuscripts which reside in the Archives. The museum has followed an arrangement of display initiated by General Pitt-Rivers, the museum’s founder. Blackwood (1970) suggests the arrangement consists of large collections by subjects, with sub-groups, geographical variation and diffusion of ideas and on occasion expression of the complete technical process, both types of display were aimed to show a classification of all forms a object can take (University of Oxford, n.d.). The museum still conforms to this type of display today. There are variations between cases – for example, the special exhibition gallery features contemporary interpretive display types. However the typological style of display is dissimilar to the majority of ethnographic and archaeological museums which choose to display material culture according to geographical or cultural areas. The density of artefacts can be compared to The Museum of Rural Life in Reading. Numerous reviews posted online regarding the PRM highlight the word repetition – for example, the cases can be interpreted as 'over-crowded'. There are suggestions of a slight reduction in artefacts, enabling a closer concentration on those which remain as some of the artefacts at the bottom-centre of the case are obscured.

However, the large percentage of artefacts on display at both museums is not coincidental and in both instances, the 'displays' are primarily visible storage, often referred to as "open-storage" or 'open access exhibitions' (Lord, B., 2001). The Museum of Reading interactive box room gallery is similar to this, as the loans boxes are visible to visitors and can be used as a teaching recourse (Reading Museum, n.d.).

Lothar P. Witteborg (1958) suggested that 'the primary purpose and function of a museum and its exhibits is to educate.' The PRM encompasses this idea as it is primarily a teaching and research institution. In addition, the curators also practice in either Cultural Anthropology or Archaeology, due to the fact that it is a University museum rather than an attempt to replicate an 'old museum'. Many museum professionals would agree that the educational function of a museum is very important (Hudson, 1975), while others argue that the 'telling a story' approach to museum display or 'Linear sequence exhibitions' (Lord, B., 2001) is the best way of achieving a 'meaningful reputation'. The PRM favours the 'exploration' layout, which enables students and visitors to make their own opinions and emotions about exhibitions, rather than a small amount of objects being picked out for them (Pitt Rivers Museum [2], n.d.). The PRM contains two types of circulation patterns, the 'Court' follows the 'Block circulation system' (Communications Design Team R.O.M, 1999), an approach which is preferable to some, as a result the museum lacks a sense of direction and guidance; dissimilar to national museums, there is no pre-planned route in which visitors can take. The 'Lower Gallery' and 'Upper Gallery' follow the 'Arterial circulation pattern' (Communications Design Team R. O.M, 1999) in which the main path is unbroken, taking museum visitors around in a fixed chronological sequence, this is appropriate for the 'Lower Gallery' which contains sequences of 'Childhood' but can be interpreted as too rigid.

The museum does not use one theme font or labelling system. While some labels have clear readability, others were written on small letter tags with even smaller writing size which makes for a very challenging read. In the 'Transport and Navigation display', the text is very word-heavy and consists of black text on a yellow background. The text, which is sub-headed 'Outrigger and Double Canoes' (Figure 1), goes in to great detail in to the development and use of both components. 'Body Art, Jewellery and Accessories' display cases contain a range of text including black printed text on a white background which engage the attention of the reader. Some of the labels found within the PRM are very revealing while others are small and hand-printed, reflecting the old customs of the first curators and editors of the museum. While this is an example of the museum conserving the history of museums, it does encroach upon the issue of empathy or the lack of it during the beginnings of Cultural Anthropology, where anthropologists did not practice in fieldwork and are considered by today's standards as "armchair anthropologists" who lacked cultural relativism (Ferraro, G. & Andreatta, S., 2010) and viewed other cultures as primitive.

Cultural artefact and human remains placed in museums are de-contextualised, but the markers and users of the object are also anonymous. Some argue that the possession and representation of foreign cultural artefacts in Western museums may hinder the source community's ability to take back the responsibility for its future (Marstine, J., 2011: 249). The PRM can be interpreted as a large "curiosity cabinet" (Ma, L. 2003). A high standard of care for human remains and artefacts made with human remains is arguably one of the PRM's accomplishments. The display of human remains is always being considered for remodelling in order to achieve the best method of communication for educational and cultural purposes and to be respectful to both the dead and the visitors. For example, in 1987 removed the Maori moko mokai (tattooed heads), replacing them with a textual explanation of their meaning and the pardon for their removal as a result of advice from a visiting member of a Maori community (Pitt Rivers Museum [1], n.d). This example does not stand alone, the museum staff work with source communities around the world in order to fully understand their collections. The case on 'Treatment of the Dead' (Figure 1) features dimmed lighting due to the organic nature of human remains, the shrunken heads are also hung from the ceiling of the cabinet perhaps to imitate the three ritual festivals where the heads would have been strung on a cord and worn (Peers' L., 2011). Despite an overwhelming popularity amongst visitors, 'Treatment of the Dead' case is not a prominent wall display, instead it is nestled behind the 'Human Form in Art' case. This may be an example of concealment to respect the dead. This is similar to the location of bog bodies in the 'Kingship and Sacrifice' exhibition at The National Museum of Ireland whereby the human remains are in glass cases, enclosed in small rotunda-like structures creating a physical barrier for those who do not which to see them (The National Museum of Ireland, n.d.).

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History is also an example of Victorian Gothic architecture, however its large glass roof over the central part of the museum with cast iron shafts (Oxford University Museum of Natural History Museum, n.d.) gives the impression of a much lighter and larger open-plan space, as a result, by comparison the PRM appears exotic. However the idea of cultural artefacts from foreign countries being identified as exotic is a misinterpretation which has long been disregarded. Interestingly, the online description of the Victorian Natural History Gallery at Ipswich Museum which contains taxidermist examples of foreign animals refers to the specimens as 'exotic' (Colchester + Ipswich Museums, n.d.). However despite the public's reputation of the PRM, perhaps due to its overall design, the museum has approximately '44,015 objects and 6,593 photographs and an unknown quantity of manuscript collections' from England (Pitt Rivers Museum [4], n.d.).

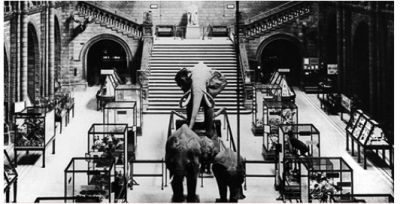

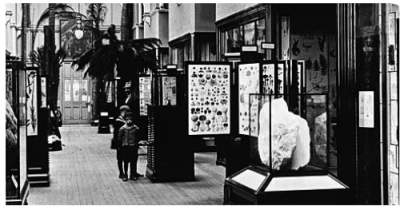

The central hall of The Natural History Museum in London in 1924 (Figure 2) and the interior view of the Botany Gallery in 1911 (Figure 3) are similar displays to the modern-day PRM. Both of which contain a number of black-framed cases containing natural artefacts. This therefore shows how other museums have changed their image while the Pitt Rivers Museum has remained with the customs of the early 1900s. However, this is not to say that the PRM has not adapted over time. While the PRM does not incorporate 3D technology, digital learning, electronic display, interactivity nor hand-held guides within its physical facility, it does have a very large web presence especially in relation to social media, namely Twitter and Blogger.com. The museum also uses Quick Response (QR) codes which can be scanned using a mobile device, offering more information concerning a particular object, other archival records and directing visitors to other web pages that may be of interest. This is a very useful tool for conserving space, especially as there is an evident lack of it at the PRM. In addition, the museum is also featured on the 'Oxfords University Museum’ app and their website contains audio and video podcasts produced by the PRM in collaboration with local film-makers, schools and academic experts from all around the world which provide an insight into the inner workings of the museum.

The absence of technology within the museum does not make it less significant than museums which use a lot of electronic display, as these can become confusing. The presence of digital technology within the PRM would distract visitors from the aesthetic pleasures of its artefacts. However, online technology used by the PRM adds a layer of interpretation for the visitor. The second phase of its development in 2008 (Pitt Rivers Museum [2], n.d.) changed the PRM from what some may have called a 'fossilised Victorian Museum' into a museum which offers a research and reference centre in sympathy with the Victorian building through the various display-related tasks such as the installation of new cases and displays, suspending the outrigger canoe and 'assessment, storage and redisplay of over 5000 objects' (Pitt Rivers Museum [3], n.d.). An area on the 'Lower Gallery' has been cleared of cases (moved to the front of the museum) in order to provide a new space for public activities and Museum Studies. The dark-coated cases did create an issue of light especially toward the back exhibition cases situated on the ground-floor, however, on further research the museum has received a grant by The Heritage Lottery Fund, supporting vital conservation and redisplay of selected cases, plus improvements to gallery lighting, in addition to a programme of free public activities which are aiming to promote human creativity and initiative. The 'Need, Make, Use' programme therefore directly tackles the question of visibility. During renovations in 2009, unobserved artefacts from the reserve collections were exhibited in the Museum’s characteristic style, therefore celebrating the museum’s more historic displays and long-cherished atmosphere (Pitt Rivers Museum [5],n.d.).

In conclusion, the PRM does try to retain of the display features and incorporate some aspects of the first anthropological museums including the style of cases, the 'exotic' feel and the hand-printed labels written by the first curators which suggest, in part, that the museum is trying to show the progression from earlier museums. However such aspects do not constitute the PRM being labelled as a 'real' museum. There is no one single mould of what a museum should be, and if anything the PRM is a refreshing change from other contemporary museums, especially 'white box' museums which hand-pick items which they believe to be worthy of display, making objects untouchable and exclusive. Instead, the PRM allows students and visitors to make their own opinions and construct their own interpretations of material culture. The museum does not express traditional views of foreign cultural artefacts being 'strange' but rather incorporates earlier traditions of material culture with contemporary traditions to show the relations and common parallels. In addition, it does not ignore the importance of e-resources which shows that the museum is making efforts to be modern.

Bibliography

- Alexander, E.P. & M., (2008). Museum in Motion: An Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums. 2nd ed. Plymouth: AltaMira Press.

- Blackwood, B., (1970). The Classification of Artifacts in the Pitt Rivers Museum Oxford. Occasional Papers on Technology, no. 11. Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum.

- Colchester & Ipswich Museum (not dated). Ipswich Museum: what can you see. Available at: http://www.cimuseums.org.uk/venues/ipswich-museum/what-can-you-see.html [Accessed on 11th December 2013].

- Communication Design Team, R. O. M. (1999). Spatial consideration in Hooper-Greenhill, E., (1999). The Educational Role of the Museum. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Edwards, E. (2003). Talking Visual Histories: Introduction in Peers, L. & Brown, A. K., (2003). Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader. London: Routledge.

- Ferraro, G. & Andreatta, S. (2010). Cultural Anthropology: An Applied Perspective. 8th ed. Untied States: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Howse, P., (2009). Pitt Rivers museum: canoes, monkey skulls and a witch in a bottle.

Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-reviews/5208631/Pitt-Rivers-m... [Accessed on 4th December 2013]. - Hudson, K. (1975). A Social History of Museums. London and Basingstoke: The Macmillan Press LTD.

- Lord, B. (2001). The Purpose of Museum Exhibitions. In B. Lord & G. D. Lord (eds.). The Manual of Museum Exhibitions. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

- Ma, L. (2003). Lingering Voices: A Case Study of the Audio Guide of Egypt Reborn at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Tourist Productions, Professor Kirshenblatt-Gimblett.

- Oxford University Museum of Natural History Museum (not dated). Virtual Tour of the Oxford University *Museum of Natural History. Available at: http://www.chem.ox.ac.uk/oxfordtour/universitymuseum/# [Accessed on 11th December 2013].

- Peers, L. (2011). Shrunken Heads. Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum.

- Pitt Rivers Museum [1] (not dated). Human Remains in the Pitt Rivers Museum. Available at: http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/human.html [Accessed on 12th December 2013].

- Pitt Rivers Museum [2] (not dated). Introduction to the displays. Available at: http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/pittrivers.html [Accessed on 11th December 2013].

- Pitt Rivers Museum [3] (Not dated). Taking the Past into the Future. Available at: http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/hlf.html [Accessed on 9th December 2013].

- Pitt Rivers Museum [4] (Not dated). The Other Within: An anthropology of Englishness. URL: http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/englishness.html [Accessed on 12th December 2013].

- Pitt Rivers Museum [5] (not dated). Need, Make, Use. Available at: http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/needmakeuse.html [Accessed on 6th Decmeber 2013].

- Reading Museum (not dated). Box Room.

Available at: http://www.readingmuseum.org.uk/collections/seeing-our-collections/box-r... [Accessed on 11th December 2013]. - The National Museum of Ireland (not dated). Kingship and Sacrifice. Available at: http://www.museum.ie/en/exhibition/list/exhibition-details-kingshipsacri... [Accessed on: 12th December 2013].

- University of Oxford (not dated). A History of the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Available at : http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/Kent/musantob/prmhist.html [Accessed on 9th December 2013].

- Watson, S. (2007). Museums and their Communities. London: Routledge.