The analysis of decorated pottery is an inherently problematic field: the scenes on Attic figured ware regularly incorporate allegory and symbolism, and thus their imagery can rarely be considered a direct reflection of ‘real’ life. Such an investigation arguably grows even more difficult when we focus in particular on the representation of women and the figurative roles they assume in vase decoration. We are constantly reminded that vase imagery was constructed by a male artist and most often for the male gaze – the principal use of figured vase ware during the Late Archaic and Classical periods was in the symposium, a fundamentally male affair. Thus the predominance of the male citizen underpins many of the ways in which the female figure was both portrayed and used on painted pottery. However, it is possible to harness these in-built distortions and use the decoration on Attic vases as a reflection of male citizenship during the era of Athenian democracy. If the vase, as a medium of social exchange and the reinforcement of cultural identity, can be considered to transmit the ideas and agendas of Athenian society to its viewer – a viewer who is predominantly male – then the inclusion of women in vase painting must contribute something to how the male citizen identified himself. Indeed the female figure operates, as will be illustrated, as a marker of sorts by which the various messages on vases are constructed, measured or reinforced. This concept is validated by the fact that women did not have full citizenship in Athenian society: the prevailing sense of indeterminacy surrounding the status of women is not only reflected in contemporary vase painting but comprises an intrinsic part of its visual dialogue. This investigation will demonstrate how the female figure came to be an abstraction, its depictions varying depending on context and style but ultimately signposting the same mechanism at work: the communication of what it is to be a male member of Athenian society and the issues in which this membership is steeped.

In many instances, erotic imagery on symposiac vases highlights an underlying anxiety surrounding male sexuality and the resultant socio-political authority of the male in Athenian society. A fragment (Fig.1) depicts three naked women amusing themselves in various ways with olisboi (leather dildos) (Kilmer 1993, 241). Kilmer concludes that this scene of companionable masturbation must obviously be lesbian in theme (Kilmer 1993, 30). However, he points out the exaggerated size and graphic anatomy of the phalli – features which are almost entirely without any human counterpart in Attic vase decoration (Kilmer 1993, 30). Therefore the olisboi represent the male form having been reduced to its essence and hyper-realised. Their indiscreet visuality conveys an ideal, but one that is hyperbolic, animalistic and primitive. The women act independently and collectively, indicating that this scene represents an inversion of contemporary social expectations. Altogether, the scene is one of women functioning without men; or at least, satisfying fundamental needs and desires without the contribution of a male citizen himself. In this way, the scene does not have to be interpreted as lesbian nor indeed are the phalli necessarily olisboi; here, the vital part of man that is required to perpetuate society has been isolated and the women put in an active role. Thus anxieties surrounding male sexuality, ‘wild’ female desire (Stansbury-O’Donnell 2011, 181), and the need for man to retain dominance are encapsulated in this scene. The picture can almost be considered an inversion of the symposium, in that it is exclusively female, sociable, and that, having been objectified and enslaved, the opposite sex provides sexual gratification. The stark erroneousness of this scene provided an imperative for the subjugation of women and, in doing so, served to strengthen contemporary social conventions surrounding male citizenship.

The perpetual Athenian struggle to reconcile a fundamental mistrust of women, evident on vases such as this, with the undeniable fact that society depended upon them was enshrined in their culture. In Euripides’ Medea, the character Jason expresses an outright desire for masculine independence of women: “Mortal men ought to produce children from somewhere else, and there ought not to be a female race; then there would be no misfortune for men…” (Euripedes Medea 573-75; trans. Mossman 2011, 133). Jason’s words, together with the potent abnormality conveyed in the tableau on the olisboi pot, recall a myth central to Athenian society and the Athenian construction of the female. This was the Athenian myth of autochthony, in which Erichthonios, the legendary King of Athens, was born after the sperm of Hephaistos was spilled on the ground when Athena rejected the advances of the blacksmith god. This myth of the founding of Athens essentially disavows women, as a race, of the biological role of motherhood and powerfully illustrates that women were perpetually considered an entity external to the polis. However, the fact of the matter was that men could not – indeed, cannot - reproduce without women. Thus it was the tension between this persistent and seemingly innate desire to undermine female citizenship and the necessity to include women in Athenian culture that gave rise to the sorts of imagery discussed on the olisboi pot. Therefore, pottery painted for the male viewer purveyed a ‘call to arms’ and a duty to assert dominance in the sexual arena; an arena which was inherently tied to the socio-political ideals of contemporary Athenian society. In this way, the female figure not only symbolised a source of tension within the political parameters of Athens, but provided a measure by which the consequences of social disruption were illustrated and the criteria for social and political harmony cemented.

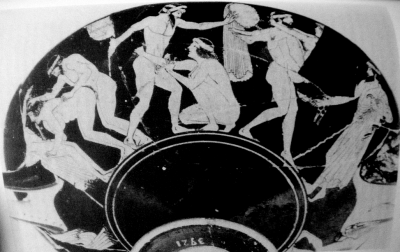

The depiction of violence against women is another way in which the female figure transcended ‘realistic’ portrayal to become an abstraction by which social tensions were communicated. On a red figure cup from 490 BC (Fig. 2), a series of women are subjected to the forceful desires of a group of men. One woman appears particularly pitiable, forced to her knees as a man, wielding a flute as if to threaten punishment, looms over her and insinuates his desire for fellation (Kilmer 1993, 252). Keuls finds this scene categorically violent (1993, 182). Kilmer by contrast argues that it is not violent at all but merely playful (1993, 118). However, we should not fixate solely upon debates of objectification or the moral treatment of women, especially given that we should always hesitate before superimposing our own modern - and largely irrelevant - values upon ancient society. Besides, such scenes should not be analysed as if they are ‘real’ reflections of daily life, given the evident tendency for Attic vase ware to deploy its decoration in a highly schematised and allegorical way. In fact, the overly directive and almost excessively masculine behaviour of the men on this cup not only indicates its artificiality, but alludes to the contemplation of broader contemporary affairs.

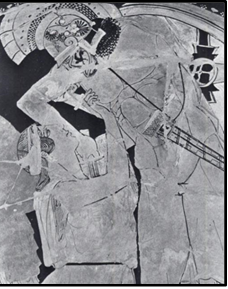

The continuity of the scene is confirmed by the overlapping feet of the figures (Fig. 2), thus informing us that this depicts a single group activity rather than several individual frames. Therefore the symposium is instantly brought to mind, in turn identifying the men involved as belonging to the upper class. The exaggerated athleticism of the men and their manifest authority - in stark contrast to the rather unflattering, ‘flabby’ portrayal of the women - render them as hyperbolic archetypes of elite values; in other words, a visual embodiment of how the kaloikagathoi identified themselves. It would be too bold to see these men as a mockery of the kaloikagathoi (and this would seem illogical since they were the target audience of such a cup) but the scene is certainly a provocative portrayal of their ideals and behaviour. The imagery perhaps serves as a warning, personifying concerns regarding the power and behaviour of the elite in era of fledgling democracy. Tension between oligarchs and democrats was a fundamental feature of the Athenian politics of this era. Plato even went as far as saying “some call it a democracy…but it is in reality government by the elite with the approval of the crowd” (Plato, Menexenus 238d1-2; trans. Ryan 1997, 954). This underlying sense of duplicity correlates strongly with the symbolism and violence in this image. In this way, the female figure is perhaps being used to represent the body politic and to conjure fears and warnings surrounding its abuse. On the fragment discussed earlier, the imperative for the subjugation of women indeed became a metaphor for the preservation of social order; where this subjugation fails, the socio-political status quo is also disrupted. Keuls discusses the popular combat between Greeks and Amazons and its exemplification of the Athenian “obsessive fear of women”: the Amazons posed a threat to Greek manhood, justifying male supremacy for the survival of social order (Keuls 1993, 3-4). When discussing instances on vase ware in which Greeks have the upper hand when portrayed fighting Amazons, Keuls notes that the Greek warrior is often shown stabbing the Amazon in the nipple (Figs. 3 and 4). She ascribes this detail to an underlying fear of women and a subsequent need to visually heighten the assault on the feminine (Keuls 1993, 4). Perhaps, if this pot is also designed to stress the need for female suppression, its overt violence could be interpreted in a similar way: as a dramatised illustration of male supremacy and male social reality.

Stewart’s analysis of the ‘erotic pursuit’ – another motif which frequently appeared on Attic vases – provides further evidence for the notion that the female figure was employed on pottery for socio-political and didactic purposes. He argues that such scenes explored rites of passage – that of marriage, in particular (Stewart 1995, 83). The ‘erotic pursuit’, if we accept Stewart’s interpretation, is highly relatable therefore to the Athenian polis context and the social expectations that comprised one’s citizenship. On an Attic red figure oinochoe from 450-400BC, a young man, clutching spears and pointing, runs after a young woman. She looks over her shoulder at him, her arms raised. As is characteristic of these scenes, the victim is dressed and there is no evidence of arousal on the part of the pursuer (Stewart 1995, 74). It is difficult to tell whether or not these snapshots are violent or playful; does the girl raise her arms in fear, or to tease? The eye-contact of the two protagonists and the fact that we simply do not know what, exactly, the end result of this scene is going to be (rape, marriage or consensual intercourse) altogether marks the image as one of tension. Stewart interprets this inherent tension as an articulation of the anxiety surrounding marriage from the perspective of young men. In reality, a young girl would have been married off to a much older man, but the fact that it is always a young boy pursuing the girl in these scenes actually validates Stewart’s idea: for it would indeed have been a young man, on the cusp of adulthood, who would have had concerns about what society expected from him once he himself became a husband, and thus a young man who would have been able to identify with the youth on this vase.

The fleeing female on the oinochoe allies with the idea that women need to be tamed by men: the spears wielded by the youth connote the phallus and the sexual dominance expected of a male citizen; the young man’s chasing of the girl reflects the need to assert this dominance over her and in his household. The scene’s withholding of its end result also supports Stewart’s reading, as it discloses a preoccupation with the process of the events displayed on the vase, and thus in the rites of passage themselves, rather than with the outcome (which should perhaps be considered inevitable, if the male has indeed fulfilled his social duty). As we have already seen elsewhere, vase decoration regularly provided an imperative for male social participation and it achieved this through the presentation of exaggerated and fictitious scenarios in which the social norm has been transposed; the ‘erotic pursuit’, in which the male has to both literally and metaphorically gain control of the female, certainly fits in with the wider scheme of this visual dialogue. Depicting the rite of passage as it unfolds leaves room for the threat of what would happen if social expectations were not fulfilled: the man, undermined by the woman, would become achreios, worthless.

Stewart points out that these ephebic pursuits were most popular between 450-425BC (the heroic and the divine types pervaded 500-475 and 475-450BC respectively) and, critically, were the final subset of pursuit before the scene went out of fashion (Stewart 1995, 74). In this way, we can see that the erotic pursuit developed from something occupied with mythology during the Archaic period to culminate in something more socio-politically oriented in the Classical period. The use of an ephebe, as opposed to Theseus or Apollo, situated an actual citizen in the scene, making it more relatable to the Athenian viewer. This adds credibility to the above notion that, as society became more politicised, so did the use of imagery on vases. The scene discussed above was found on an oinochoe, one of many vessels used in connection with wine. Oinochoai were probably used in Athens during the Anthesteria, one of the four Athenian festivals held in honour of Dionysus (The Beazley Archive, 2012). The distinctively Athenian character of this ritual context, as well as its scope for public display and the reinforcement of Athenian social identity, bestows further significance on the decision to paint such a scene upon this vase. The dissemination of this imagery in such a highly socio-political context ratifies the fundamentally Athenian cultural archaeology of the ‘erotic pursuit’ and the messages it is likely to have transmitted.

Overall, the symposium was emblematic of the ideals of the elite male viewer and the nature of the society in which he existed. The symposium must be regarded as a homo-social environment, itself reinforcing the expectations and relationships of upper class men in Archaic and Classical society. Thus vases used in this context were instruments in its ideological aims. But one wonders how their dialogue was meant to be received by the female viewer. These images, so profoundly suggestive of male citizenship, were perhaps intended to speak to women too: scenes of submission and courtship must surely have reinforced what was expected of wives and daughters. However, any woman who viewed these images on account of her being present at a symposium was most likely to have been of lower class, and only there to satisfy the needs of the male participants; respectable wives and daughters were kept largely isolated in the gynaikeion, and probably rarely exposed to such imagery (Blundell 1995, 139). But even imagery which must have been constructed with a female viewer in mind only serves to reiterate the inevitability of the male perspective. A pyxis, which would have held perfume or oils, frequently featured scenes of abduction (Stansbury-O’Donnell 2011, 189). They were often given as wedding gifts (Stansbury-O’Donnell 2011, 189) and thus a woman’s receipt of a pyxis which conveyed marriage as abduction only anticipated her ensuing subjugation by her husband. Even epinetra, unlikely to have been both purchased and used by men (Stansbury-O’Donnell 2011, 189), would have been painted by male artists and regularly featured symposiac scenes similar to those already discussed as well as amazons – mythological figures which were threateningly emblematic of the consequences of allowing the female free rein – being killed by Greeks (The Beazley Archive, 2012).

Therefore the female figure, as a motif of painted pottery, facilitated the exploration and validation of Athenian civic values. These civic values themselves were inherently configured according to the male perspective and male socio-political dominance in Athenian culture. The ambiguity surrounding the female figure and her role in society was both reflected and exploited in art, and the ‘unruly’ woman was frequently a byword for the necessity of male authority. Her problematic nature and unresolved incorporation into the polis enabled her to assume the qualities of an abstraction, through which an artist could allude to contemporary affairs and ideology. By her antithetic nature, the female figure performed the very principles of citizenship, most commonly through a language of negation. Ultimately, however, whether she illustrated good citizenship through passive subjugation or actively denoted bad citizenship by being out of control, the female figure was a tool in the Athenian artistic discourse emblazoned upon contemporary pottery – pottery which was in turn primarily used by the male participants of the fundamentally male symposium. She was a paradigm for male social education and an index according to which the expectations and criteria of Athenian male identity were reinforced.

Bibliography

- Blundell, S. (1995). Women in Ancient Greece. London: British Museum Press.

- Euripedes Medea; Trans. Mossman, Judith (2011). Euripides: Medea. Oxford: Aris and Phillips.

- Keuls, E. C. (1993). The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens. London: University of California Press Ltd.

- Kilmer, M. F. (1993). Greek Erotica on Attic Red Figure Vases. London: Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd.

- Plato Menexenus; Trans. Ryan, Paul (1997). Menexenus. In Cooper, J. M. (Ed.). Plato: The Complete Works. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. 950-964.

- Stansbury-O’Donnell, M. D. (2011). Looking at Greek Art. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Stewart, A. F. (1995). ‘Rape?’ In Reeder, E. D. (Ed.). Pandora: Women in Classical Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 74-90.

- Von Bothmer, D. (1957). Amazons in Greek Art. Oxford : Clarendon Press.