Introduction

The Battle of Bosworth has long been viewed as an iconic moment in British history: immortalised by Shakespeare, the battle saw the last death in battle of a reigning English monarch, the end of three decades of civil war, and the beginning of the Tudor dynasty (Burne 1950, 286; Foard & Curry 2013, xiii; Battlefields Trust 2016). The recent announcements of the discovery and identification of the Richard III’s skeleton under a car park in Leicester and artefacts from the Bosworth battlefield have received much publicity (Mack 2014; Elton 2015). Archaeological investigation appears to have proved the location of the battlefield, some 3 kilometres away from the traditional site (Foard 2010, 26), and the skeleton has been subject to a great deal of scientific analysis, as well as public debate. The recent controversial decision by Historic England to allow development on the edge of the battlefield (Johnson 2018) has kept Bosworth in the public eye and brought into question the wider issue of the protection of England’s battlefields. Beginning with an introduction to battlefield archaeology and the impact of the battle itself, this article will discuss the impact of investigations at Bosworth and the search for Richard’s remains, and how evidence relating to these discoveries has implications for research within the field of battlefield archaeology.

Battlefield Archaeology and the Battle of Bosworth

Britain is a landscape dominated by war (Lynch & Cooksey 2007, 19), but until recently the study of battles and conflict has been the exclusive domain of the military historian, leading to what Carman (2012, 15) describes as ‘a linear narrative of cause and effect [and] a highly functionalist interpretation’. Using archaeological principles to study ancient or historical conflict can provide evidence of what actually occurred on a particular day at a particular time (Sutherland & Holst 2005, 3). The study of battlefield archaeology is a relatively new discipline, although it can trace its foundations back to the pioneering work during the 19th century of Edward Fitzgerald and Sir John George Woodford at Naseby and Agincourt respectively (Sutherland 2005, 247; Sutherland & Holst 2005, 13; Sutherland 2015, 190). Originating with the ground-breaking research at Little Bighorn in the USA in the early 1980s (Figure 2) (Scott et al. 1989; Sivilich & Scott 2010), battlefield archaeology began in Britain with the investigations at Naseby and Towton in the mid-1990s (Sutherland & Holst 2005, 13-14; Foard 2012, 14; Foard & Morris 2012, xii; Carman 2012, 812).

Since then, there have been significant advances in the approaches and methodology used in the practice of battlefield archaeology, such as the but like other specialist disciplines, it is not without its complexities (Foard 2007, 134; Scott et al. 2007, 1; Sivilich & Scott 2010). Therefore, battlefield archaeology requires a multi-disciplinary approach, including the study of documentation, landscape, artefacts, and spatial analysis (Foard 2007, 133). Between 2005 and 2010, this approach was used to discover the location of arguably one of the most famous English battles: The Battle of Bosworth (Foard & Curry 2013, xiii-xv).|

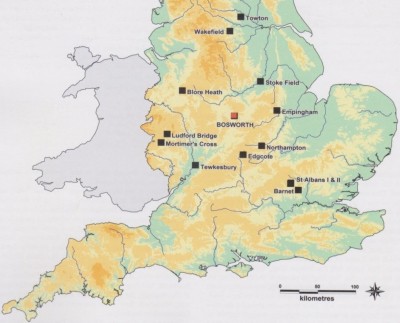

The Battle of Bosworth in 1485 was one of the last of a series of battles fought across England between 1455 and 1487 (Figure 3), a period that would later become known as the Wars of the Roses (Pollard 2001, 5; Foard & Morris 2012, 81).

The outcome of the battle is well known: Richard was killed during the battle and Henry Tudor was crowned King Henry VII, ushering in a Tudor dynasty that ruled England and Wales for over a hundred years (Burne 1950, 286; Bennett 1985, 1; Foard & Curry 2013, xiii; Battlefields Trust 2016). Although Henry was forced to defend his crown two years later at the Battle of Stoke Field, his victory at Bosworth is considered to have been the final chapter in the Wars of the Roses, ending 30 years of English civil war (Burne 1950, 305; Bennett 1987, 3; Pollard 2001, 35; Foard & Curry 2013, xiii). Richard’s remains disappeared shortly after the battle, rumoured to have been thrown in a river or buried somewhere in Leicester (Buckley et al. 2013a, 15; 2013b, 520; Langley 2014, 21), but the location of the battle remained well known as the site became an area of interest for many who wished to visit the battlefield. However, memory of the battle became obscured over time so that, by the 18th century, it was thought that the battle had taken place on Ambion Hill (Hutton 1788, 54-55; Foard & Curry 2013, xv). It was not until the late 20th century that historians began to question the location of the battle (Bennett 1985, 14; Foss 1988, 21-22; Foss 1998, 21-23; Jones 2002, 148; Foard & Curry 2013, xv). When plans were made to refurbish the visitor centre on the site, a project was set up to use battlefield archaeology to locate the true site of the battle (Foard & Curry 213, xvi). Just one year after the Bosworth project finished, a team from University of Leicester Archaeological Services was commissioned to carry out a desk-based assessment to review the historical and archaeological evidence for Greyfriars priory in Leicester (Buckley et al. 2013a, 15; 2013b, 520-521; Langley 2014, 21-22). This was the first step in the search for the lost remains of Richard III, a search that attracted large amounts of public and media interest, both during the investigations and following the recovery, identification, and subsequent burial of the skeleton (Mack 2014; Elton 2015; Warzynski 2016a; Warzynski 2016b).

Impact of the Discoveries of Richard III and the Bosworth Battlefield

The two separate archaeological investigations over a seven-year period that saw the discoveries of the apparent remains of Richard III and artefacts suggesting the location of the Bosworth battlefield (see Figure 4) have had a significant impact in many areas. The media coverage given to Richard III alone has seen a major increase in the popularity of archaeology in general and, for the city of Leicester, the discovery of Richard has led to a substantial boost to the local tourism and economy (Mack 2014; Warzynski 2016a; 2016b). However, at Bosworth, the Bosworth Battlefield Heritage Centre and associated tours remain on and around Ambion Hill. Whilst the tour guides acknowledge and highlight the investigations at the site, and that it is no longer thought to have taken place on Ambion Hill, tours of the new location are restricted to a small number per year (Whitehead 2016).

Bosworth Battlefield

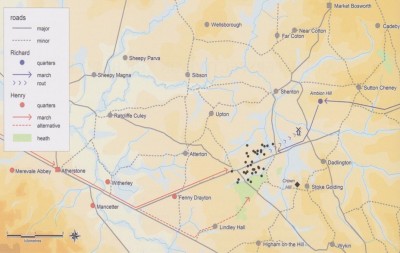

The investigations at Bosworth provide a textbook example of how to research and systematically survey a medieval battlefield. Over the course of five years, the battlefield archaeologists used data from historical documents and maps, landscape archaeology, metal detecting survey, and ballistics and scientific analysis to formally identify the site of the Battle of Bosworth (Foard & Curry 2013, xiii-xx). However, this approach was only possible due to the project receiving significant funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund (Foard & Curry 2013, xvi). An element of luck also played a part: the first piece of confirmed battlefield evidence (Figure 5) was found in the last few days of the original timetable (Foard 2010; Foard & Curry 2013, xviii).

of the Bosworth project which provided the first evidence of the battlefield (after Foard & Curry 2013, xix).

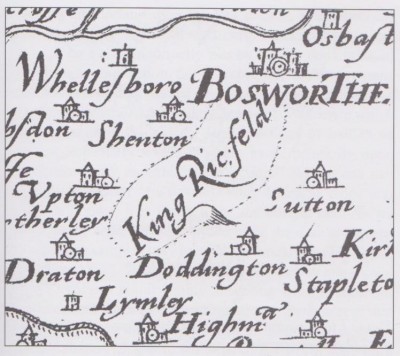

Had the timescale for the project been just a week shorter, no evidence would have been found from the battlefield and the end result of the project would have only established areas where no evidence of the battle had been found. The Bosworth project team also benefited from a considerable amount of contemporary and secondary documentary sources referring to the battle. The significance of the battle was recognised even from an early stage, and much work has already been dedicated to it. For example, on Saxton’s 1576 map of England (Figure 6), Bosworth or ‘King Richard’s Field’ is the only battle site given on the map (Foard & Curry 2013, 1).

Ric. feld' (after Foard & Curry 2013, 3).

The abundance of documentary evidence proved useful in helping the project focus on search areas (Foard & Curry 2013, 1-16). The project can be considered a success, having used a multi-disciplinary approach to battlefield archaeology to uncover the location of the battlefield and provided a new insight into the archaeology of English medieval battles involving the use of gunpowder weapons, which prior to this primarily existed only in the work at Towton (Sutherland & Schmidt 2003, 15-20). The project also raised important methodological issues concerning battlefield archaeology, particularly the inadequacy of metal detecting in 10 meter transects in non-ferrous mode (Foard & Curry 2013, 195). However, the investigations are not entirely conclusive. The flat plain where evidence of the battle has been found matches the contemporary descriptions of the battlefield, but the site lies in Upton, not Dadlington, where many contemporary sources claim the battle took place. There is also the now famous silver-gilt boar badge (Figure 7), found on the battlefield, claimed to be ‘sufficient in its own right to quell any lingering doubt that the battlefield has been located’ (Foard & Curry 2013, 124).

Whilst it is likely the badge represents someone of high status in Richard III’s retinue, it may not necessarily indicate the location of the battlefield. It is known that the Bosworth battlefield site attracted many visitors after the battle (Foard & Curry 2013, 2). The badge could simply be another result of tourism – dropped or discarded by one of Richard’s former supporters visiting the site – and therefore may not relate directly to the battle (Sutherland 2014, 1000).

battlefield (after Foard & Curry 2013, 124).

In August 2018, a planning application was submitted for construction of a track for autonomous vehicle testing on the edge of the Bosworth battlefield (Humphrys 2018). The application and subsequent acceptance by Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council on the advice of Historic England caused outrage amongst many (Johnston 2018), including the Battlefields Trust (Humphys 2018; Battlefields Trust 2018a; 2018b) and the Richard III Society (BBC News 2018; Richard III Society 2018), even prompting a debate in Parliament (D’Arcy 2018). The Battlefields Trust in particular, whose remit is to campaign both locally and nationally to defend battlefields from inappropriate development or even destruction, penned a statement of opposition which not only fought for the protection of the battlefield but also called into question the methodology used to judge the risk posed to the site (Battlefields Trust 2018b). Although the application to build the test track has been accepted, the debate is far from over and has raised questions about the way in which assessments on the registration and protection of battlefields in England are carried out. There are around 200 potential battlefield sites in England alone, yet only 46 of these are currently registered as protected areas (Foard and Morris 2012, 175-179. The Battlefields Trust has long argued for greater protection of the 46 registered sites but also for the means to register further sites, and has used this new threat to Bosworth to repeat calls to Historic England to reinstate the Battlefield Panel, abolished in 2015, in order to provide specialist battlefield expertise when it comes to applications such as these (Battlefield Trust 2018b). What outcome this will have for the future of England’s battlefields remains to be seen, but the reaction to this development continues to highlight the importance of this battlefield, and the risks posed to similar sites across the country.

The King in the Car Park

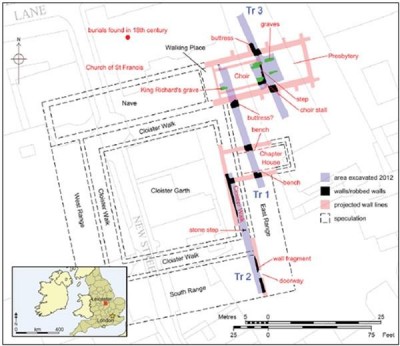

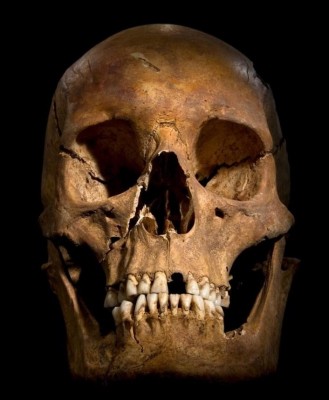

The discovery of skeleton 1 in the Choir at Greyfriars in Leicester in 2012 (Figure 8), later confidently identified as the remains of King Richard III, attracted worldwide attention (Kennedy 2013; University of Leicester 2013).

The considerable amount of media coverage of Richard’s discovery and reburial has also impacted archaeology due to the legal battle resulting in the decision to bury his remains in Leicester (Mohamed 2013). The original plan to reinter Richard’s body in Leicester Cathedral was in keeping with the archaeological precedent that human remains be reburied in the nearest consecrated ground (Carson et al. 2014, 37; Pitts 2015). Burial in Leicester Cathedral was a condition of the exhumation license given by the Ministry of Justice, should Richard’s remains be found (Carson et al. 2014, 38). The extended court battle over the right to bury Richard’s remains in Leicester Cathedral raised the issue of the legal and ethical concerns over archaeologically excavated human remains (Mohamed 2013).

Concerns have also been raised over the identity of the remains. Whilst the archaeologists at ULAS state ‘beyond reasonable doubt that Skeleton 1 is the remains of King Richard III’ (King et al. 2014, 2), some academics remain unconvinced. Historian Michael Hicks and archaeologist Martin Biddle have both called the findings into question: Hicks stated that none of the evidence can prove beyond reasonable doubt that the skeleton is Richard, in particular questioning the DNA and radiocarbon evidence (McFarnon 2014; Milmo 2014). Biddle suggests that ‘something akin to a coroner’s court should be set up to consider all the evidence’ (quoted in McFarnon 2014). Author Dominic Selwood (2015) wrote an article for The Telegraph arguing the case against the identification of Richard, using some of the objections raised by Hicks and Biddle. A scan of the comments section of the article reveals a clear stubbornness from the public to acknowledge that there could be any uncertainty over the identity of the remains. The media frenzy surrounding the identity of Richard has reached a point where to question the results leads to a critical backlash from the public. However, Hicks, Biddle, and Selwood all raise valid points. Although much of the evidence does point towards the skeleton being the remains of Richard III, it cannot be conclusively proved: the DNA evidence only shows that the skeleton was descended from the female line of Richard’s maternal grandmother, who had 16 children, and the radiocarbon dating and trauma analysis only demonstrate that the individual appears to have died in battle during the period of the Wars of the Roses, meaning there is no 100% certainty it is Richard III (King et al. 2014, 1-3; McFarnon 2014; Milmo 2014; Appleby et al. 2015, 253).

Regardless of the skeleton’s identity, it is from the battle trauma found on the skeleton that archaeology has benefited most. Prior to the discovery of this particular skeleton, the best examples for medieval battle trauma were in the mass graves found at Towton, excavated between 1996 and 2005, where a number of individuals believed to have been killed at the Battle of Towton displayed evidence of battle trauma (Novak 2000, 91-100; Sutherland 2016, 79). If the skeleton is that of the king killed at Bosworth, then it is possible to use the extensive weapon trauma found on the skeleton, particularly the skull (Figure 9), to compare and support the evidence of similar injuries found on the individuals at Towton (Sutherland 2016, 82-84). It is also possible to describe, in detail, exactly how the last English king to die in battle was killed, including the weapons used to strike the fatal blows (Buckley et al. 2013b, 536; Appleby et al. 2015, 257-258; Sutherland 2016, 85-86).

Conclusions

The reported discoveries of Richard III and the true location of the Bosworth battlefield have had both positive and negative effects on the study of battlefield archaeology. The investigations at the Bosworth site have provided an excellent template for the methodology of battlefield archaeology on a medieval battle site, but require sufficient funding, time, and enough historical documentation to allow for such a full and thorough survey. Even this thorough multi-disciplinary approach has left questions about the battlefield site. The discovery of Richard’s skeleton provided a relatively unique opportunity to study the remains of a known/named victim of battle trauma, comparable with those from Towton. But whilst the general public and many academics remain convinced of the identity of the bones found at Grey Friars, there are some who are not wholly convinced by the claim that it is the lost king. Due to the intense media coverage of the event, to even question the possibility that the skeleton may not be Richard can draw criticism. Although the publicity around Richard’s discovery and identification have led to a rise in interest in archaeology and the subject of medieval warfare, it has not been without controversy, with the year-long legal battle over the burial place of the King’s skeleton displaying some of the disagreeable outcomes of excavating human remains, and the acceptance of a development application that may destroy part of the Bosworth battlefield has only continued to fuel the interest and controversy around this nationally important site.