Introduction

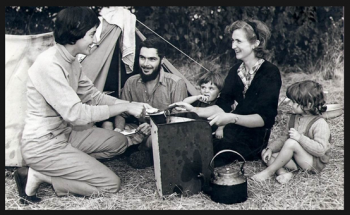

Dr Bridget Allchin (1927-2017) was an expert in lithics, South-Asian archaeology and fieldwork (Figure 1) (Coningham, 2017, Hawkes, 2017). Allchin and her husband were known as the ‘Auntie’ and ‘Uncle’ of South Asian studies; they never failed to promote it and attempted to make it as accessible as possible for everyone, including frequently hosting fellow archaeologists, students, and visitors from South Asia (Ball, 2015, Coningham, 2017, Hawkes, 2017).

Allchin held many academically focused roles outside her fieldwork, including; secretary-general of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, editor of the Afghan Studies journal (she steered it to becoming the South Asian Studies journal after the Afghan conflict escalated in 1985), a founder, secretary and chair of the Ancient India and Iran Trust (the five founders purchased a house in Cambridge to be the headquarters and donated their private libraries), a joint director of the British Archaeological Mission in Pakistan, founder of the European Association of South Asian Archaeology and Art, and a fellow at Wolfson College Cambridge (Coningham, 2017, Hawkes, 2017). In 2014 she was awarded the Royal Asiatic Society Gold Medal in recognition of her pioneering contribution to South Asian archaeology (Coningham, 2017). Allchin began her career with a degree in African Studies at Cape Town University and then moved back to Britain in 1950, securing a place on a doctorate course focusing on the Late Stone Age of South Africa at the London School of Economics after a ten minute interview with the then Director of the Institute of Archaeology, Vere Gordon Childe (Coningham, 2017). Her focus shifted to South Asia when assisting her husband, Raymond Allchin, on his PhD trip to India in the 1950s, publishing her own PhD, The Stone-Tipped Arrow: Late Stone Age Hunters of the Tropical Old World, in 1966 (Coningham, 2017, Hawkes, 2017). Including exceptional field discoveries, Allchin also laid the foundations for, and pioneered, the interdisciplinary method that is standard across archaeology today (Hawkes, 2017). This essay will discuss the contemporary theoretical contexts she was working with and suggest how they influenced her work. It will then explore the impact of her work on archaeological thought then and now.

Contemporary theoretical contexts

The prevailing theoretical framework in archaeology changed several times throughout Allchin’s work; prior to the 1960s culture history was prevalent, between the 1960s and 1970s the New Archaeology, then Processualism took over, to be followed in the 1980s and 1990s by Post Processualism (Miksic, 1995, Johnson, 2011). This section of the essay will provide a summary of each theory before illustrating how they affected Allchin and her work.

Culture history constructs typologies within material cultures, which are then attributed to a group of people and labelled a ‘culture’ (Johnson, 2011). Therefore, if a set of stone tools at one site are similar or the same as a set of stone tools at another site, they will be linked together and those sites will be said to be part of the same ‘culture’. This approach, through the amplified differences between cultures and typologies, tends to assume that most changes originate from outside that culture and therefore, must have either diffused from another culture or were transported in through the migration of people. It is usually descriptive, avoiding ‘how’ and ‘why’ these changes occurred, preferring to rely on the assumptions that material culture is an expression of cultural norms, and that these norms define what a culture is (Johnson, 2011).

New Archaeology critiqued culture history; arguing that archaeology needed to become more scientific and anthropological, seeing culture as a system (Johnson, 2011). New Archaeology explores the relationships between these systems, and their subsystems, showing how the overall cultural system adapts to its outside environment. They also thought about cultures, not as unchanging, but as a constantly evolving system moving from simple to complex (Johnson, 2011). The coalescing of the individual points of New Archaeology eventually formed Processualism; where the focus is on the process and scientific technique leading to increasing interdisciplinary studies, often collaborating with the natural sciences (Miksic, 1995, Johnson, 2011). The rise of Processualism was described by Clarke (1973, 1) as ‘the loss of disciplinary innocence’ through the expansion of ‘consciousness’, claiming ‘the price is high but the loss is irreversible and the prize substantial.’ Processualism was the result of the journey through consciousness, self-consciousness, and critical self-consciousness where the archaeologist is explicit about their own biases in order to produce a more scientific and informative result (Clarke, 1973, Johnson, 2011).

However, Processualism was also replaced. Post processualism arrived in the 1980s and, like New Archaeology, it is a set of themes characterising a period (Johnson, 2011). Post-processualists argued that separating theory and data is impossible, so the positivist view of science is also impossible, and assumptions about data are always made therefore, interpretation is always hermeneutic (Johnson, 2011). They rejected materialistic and idealistic views arguing that a person’s opinion of an entity can change depending on their ongoing experiences with that entity (Johnson, 2011). Processualism wanted to announce biases, post processualism realised that this extends to the political context of the archaeologist and their personal political and moral views. Post processualists also wanted to increase emphasis on the individual (culture history was fairly general, and processualism even more so in this area); they have agency and their thoughts and values are important, therefore they should be studied in their own right (Johnson, 2011).

These changes in theory are major alterations, affecting anyone writing or studying at the time. Allchin began her career in the 1950s with culture history as the prevailing theoretical context, publishing a few works in this period such as Morhana Pahar: A Rediscovery (1958) and A Late Stone Age Site Near Kondapur Museum, Andhra Pradesh (1959) (co-authored with S. Satyanarayan) (Figure 2) (Coningham, 2017). In these studies the art and lithics, respectively, are compared to similar examples in the locale, perhaps trying to assign them to a typology and therefore, integrate them into the network of cultures and influence of ideas common in culture history (Figure 3) (Allchin, 1958, Allchin and Satyanarayan, 1959, Johnson, 2011).

The Stone-tipped Arrow (Allchin’s PhD thesis, 1966) marks the centre of the transition period between culture history and New Archaeology, a change reflected in the work. It describes, in true culture history style, the numerous cultures present across Africa, India, Indonesia and Australia, with a focus on Allchin’s lithics specialism (Allchin, 1966). The climate of the various areas from the Pleistocene are described and past cultures are explained using modern ethnographic studies, with an emphasis on their imminent disappearance (Allchin, 1966, Inskeep, 1967, Binford, 1968). The descriptive nature of this piece, mainly a collation of other works, contrasts with the new explanatory directive of Processualism (Binford, 1968, Johnson, 2011). However, where this study sits most on the fence, is in its conclusions surrounding the uniformity between contemporary cultures and whether this is due to independent evolution or the diffusionist model of culture history. Allchin advises diffusion as the main source, but does suggest some independent evolution (favoured by Processualists) may be involved (Allchin, 1966, Binford, 1968, Johnson, 2011).

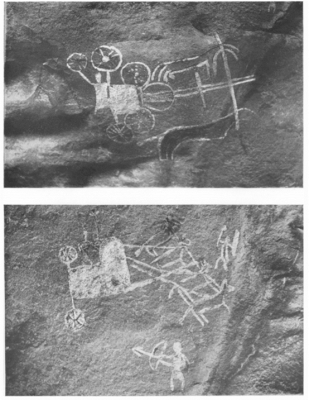

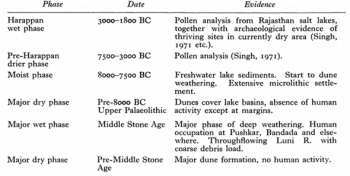

However, Allchin’s work fits the processualist mold better than that of culture history. She was a strong advocate for the interdisciplinary approach that became standard practice in archaeology (Coningham, 2017, Hawkes, 2017). This is clear in her landmark study of the Thar Desert between 1969-1976: The Prehistory and Palaeogeography of the Great Indian Desert (Allchin et al, 1978). The team was interdisciplinary in its exploration of the desert, Goudie being a geomorphologist by trade, operating for eight seasons on a small budget of just £12,000 (Coningham, 2017). They investigated the human and environmental state of the Thar Desert during the late Pleistocene to understand how the two interacted with each other (Allchin et al, 1978). The project disproved the previously widespread concept that the Thar is a recent Holocene creation from man-induced aridification or desertification, and post-glacial climatic desiccation; proving that it is much older; in fact dating to the Palaeolithic (Coningham, 2017). They demonstrated the benefits of interdisciplinary studies, in particular combining archaeology and environmental surveys, without needing to excavate. Davis (1979, 1) claims that this study broadened research emphases and perspectives with a lasting impact on the subject. Additional research concerning the Thar Desert is presented in the 1973 paper The Former Extensions of the Great Indian Sand Desert, again by Goudie, Allchin and Hegde, where they provide a possible chronology for its late Quaternary climatic phases (Figure 4).

Two of Allchin’s publications in the Postprocessualist era (1980s and 1990s); The Palaeolithic of the Potwar Plateau Punjab, Pakistan; A Fresh Approach (1981), and her chapter, The Environmental Context in The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States (Allchin and Erdosy, 1995), indicate that Allchin continues to lean towards processualism (Johnson, 2011). The Potwar Plateau study summarises the first season of fieldwork by the Cambridge University Archaeological Mission to Pakistan in the late 1970s (Allchin 1981). In true ‘Allchin style’ this project also considered the geological and geographical contexts of the sites, but never expands into the tenants of post processualism, such as a focus on the individual and their agency, or beginning to acknowledge inherent and unavoidable biases (Allchin, 1981, Johnson, 2011). Even by 1995 Allchin was still focussed on interdisciplinary projects that have, from a post processualist standpoint, a wide focus; the interest is usually in lithics and how they integrate with climatic changes to reveal alterations in the culture responsible for their creation (Allchin and Erdosy, 1995). This focus is perhaps a relic from culture history and the obsession with material culture, combined with the more scientific and interdisciplinary approaches of processualism which encompassed the bulk of her career.

Changes in archaeological thought

Allchin’s main contribution to archaeological thought is her dedication to the interdisciplinary approach, prior to its introduction as standard practice (Hawkes, 2017). However, this is not her only contribution; under her direction many important discoveries were made in southern Asia, including the Thar Desert study, but perhaps foremost among them being two million year old worked quartzite from Riwat (1983) by the British Archaeological Mission to Pakistan, where Allchin and her husband were the directors (Allchin and Allchin, 1988, Dennell et al, 1988, Dennell, 2004). Dating included the reverse polarity inherent in the sediment, setting it between 700,000 and 2.5 million years ago, and then refined using the fission track method (Allchin and Allchin, 1988, Dennell et al. 1988, Dennell 1995). This was groundbreaking, as Dennell et al. (1988, 9) remark, because ‘it is considerably older than any well-provenanced find of either hominid fossil remains or artefacts from Eurasia’. This necessitated the re-examination of prehistoric chronology; the previous belief being migration into Asia around 1.5 million years ago, substantially after 2 million years ago (Dennell, 1995). This resulted in the suggestion of several new theories, including the distribution of Homo habilis as far east as Pakistan, Homo erectus being an Asian lineage as old as Homo habilis, Homo erectus migrating from Asia to Africa, or an entirely new hominid could be responsible (Dennell et al, 1988, Dennell, 1995). Therefore, Allchin’s work directly contributed to a complete rethinking of our human history.

Allchin and her husband were also known for compiling records of cultural sequences in Southern Asia pre-500 BC from published and unpublished records in the volume, The Birth of Indian civilization: India and Pakistan before 500 BC (1968: unfortunately this book was inaccessible) (Sharma, 1971, Coningham, 2017). Fairservis (1970, 1) labelled this book as “certainly the best and most up-to-date source on the prehistory of India now available”. It has two sections; one discussing the ‘when’ and ‘where’ of the cultures, including geographic and climatic backgrounds, and the next examining settlement patterns, economy and agriculture, craft and technology, and art and religion (Fairservis, 1970, Sharma, 1971). The Birth of Indian Civilisation, like some of Allchin’s other works, argues for the culture history diffusion model where most developments are traced to western Asia; Sharma (1971) believes this idea of development spreading from the west is a British tradition highlighting bias within the authors. Allchin again incorporates an interdisciplinary approach with the typical focus on environmental and geographic change (Fairservis, 1970, Sharma, 1971). However, Wheeler (1969) is critical of the volume, suggesting the term ‘civilisation’ can only be applied once the book moves into the earliest settlements of Baluchistan and the Indus Plains. He also believes that the radiocarbon dates used are incorrect as they do not account for the error margin or issues with dating in this period meaning that the dates could be later. Wheeler’s (1969) main issue with this is that the Harappan civilisation is described as only lasting four centuries; he thinks it lasted longer citing the links between the Harappan and Sargonid civilisations as being a more accurate, and longer, chronology. The radiocarbon dates are mainly from small towns and villages, so it cannot be assumed that the major Harappan cities declined at the same pace or time (Wheeler, 1969). Wheeler has written several books on the topic, The Indus Civilisation (1968) and Early India and Pakistan: to Ashoka (1959), although both Fairservis (1969) and Ghaswala (1969) prefer the Allchins’ compilation to Wheeler’s, arguing that his are less detailed and are of a narrower focus.

Conclusion

Allchin was primarily influenced by the culture history and Processualist movements, which covered the bulk of her career, shown by her prominent role in the development of the interdisciplinary approach, allied to Processualism, and a continuing faith in the diffusionist model, now considered a relic of culture history. She has played a major role in South Asian archaeology through her groundbreaking discoveries, her dedication to promotion through journals, associations and trusts, and being an important female role model for both students and professionals. In line with making South Asian archaeology more accessible she and her husband collated vast amounts of information to create one volume containing all of the available information for the area making it much easier to study (Allchin and Allchin, 1968). Before 1970 South Asian archaeology was seen as a branch of either Indian, Chinese or Far Eastern studies, but the Allchins and the arrival of Processualism made it a prominent field in its own right (Miksic, 1995). She and her husband dominated the field of South Asian archaeology in Britain for many years from the 1950s (Ball, 2015).