Introduction

The progression from the Oldowan technocomplex to the Acheulean is one of the most

significant shifts in the archaeological record of the Palaeolithic. Discoveries in recent years

have put the date of this transition much earlier than previously thought, raising questions

about the assumptions made of the period (Lepre et al. 2011). It had previously been

considered that the Acheulean appeared c. 1.5 Ma. It was associated with Homo erectus

who, it was previously thought, exported this technology out of Africa and around the Old

World. However, recent discoveries at Kokiselei 4 in West Turkana, Kenya have pushed this

date back to 1.76 Ma. This would make it possible for other hominins to have been

responsible for the technology. The Acheulean is so important due to its type artefact; the

bifacial handaxe. The Acheulean handaxe is significant due to its seemingly universal

symmetry and a possible aestheticism previously unseen in stone tool manufacture. This

paper will explore the current arguments for why this symmetry exists, comparing the

functional, aesthetic, and social explanations. By examining these theories in relation to the

earliest evidence for the Acheulean at Kokiselei 4 an evaluation of the initial reasons for the

development of bifaces can be made. An assessment will be made as to whether it was due

to cognitive developments or functional purposes from the outset.

The site of Kokiselei 4

The earliest evidence for the Acheulean, in the form of unifacial and bifacial handaxes,

comes from Kokiselei 4, in the West Turkana region of Kenya, dating to c. 1.76 Ma (Lepre et

al. 2011). The site was excavated between 1994 and 2006, with most of the material found

at the surface (Arroyo et al. 2020, 4). The assemblage was made up of unifacial and bifacial

crude handaxes, pick-like tools, cores, and flakes which were most commonly produced

from local cobbles or volcanic rock (Gallotti 2016, 11; Lepre et al. 2011, 82).

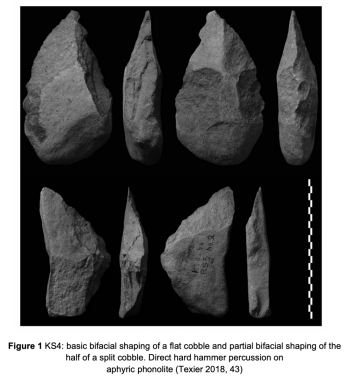

While KS4 is considered to hold the earliest examples of the Acheulean industry, it is

in a rudimentary form compared to the bifacial handaxe that is apparent later in the

Pleistocene. As can be seen in Figure 1, the shaping covers less than 50% of the surface;

there is a lack of invasiveness on the cobble and the knapping does not modify the proximal

part of the blank, which produces a variety of configurations (de la Torre 2016, 7; Gallotti

2016, 12). This is quite removed from the perfect symmetry of later handaxes. However, it is

clear from the specimen in the top right of Figure 1 that an attempt at symmetry is being

made, even at the ‘proto-Acheulean’ stage represented at KS4.

The techniques employed in the production of tools at KS4 display that the hominins

responsible were overcoming a major technological gap, with these tools corresponding to

the first stage of a technical lineage (Gallotti 2016, 12; Texier 2018, 45). The flakes were

created by splitting large cobbles using a heavy hammer and anvil, a technique not utilised

in the Oldowan (Texier 2018, 45). The assemblage at KS4 provides evidence for the two

varying chaînes opératoires of the Acheulean and the Oldowan, indicating that there was

more than one tool-making hominin between 2 and 1.5 Ma, each with their own behavioural

aptitudes (Lepre et al. 2011, 84-85).

It is generally accepted that the Acheulean has its origins in East Africa. Yet the

evidence at KS4 may either indicate that it was a continuum from the Oldowan in the same

region, or that it was imported from an unknown location (de la Torre 2016, 8; Lepre et al.

2011, 82).

Symmetry in bifacial handaxes

There has been extensive research into the reasons why Acheulean handaxes appear so

uniformly symmetrical across the broad temporal and spatial region they inhabit. The three

main theories explaining this phenomenon are that: it is for a purely functional purpose; it is

based in the evolution of neurological responses to symmetry and aesthetics in early

hominins; or that it is a method of signalling in early societies, although there is debate over

what purpose this signalling might have.

Functional purpose

The initial view of why Acheulean handaxes are produced with such high levels of symmetry

was one of a purely functional tool that had become more advanced than its Oldowan

predecessors to fulfil new capacities such as increased meat consumption (Gamble et al.

2011, 120-121; Shipton 2019, 154). Handaxes are likely to have been used in several

different tasks, such as the butchering of animals, cutting wood, slicing meat and chopping

vegetables (Mithen 2003, 264). The functional argument suggests that variability in stone

tools is required as the tool shape depends on the physical properties of the task it has been

created for (Key and Lycett 2017a, 91). This is why a handaxe would exist, even if flakes

could be used for the same tasks. Variability outside of this basic description is explained as

a need to test a range of tool forms to better recognise the relative performance qualities of

different modes (Key and Lycett 2017a, 91-92), explaining the outliers sometimes found,

such as very large or very small handaxes.

There is evidence that more skilfully made, time-consuming handaxes are more

effective at butchering meat, making the cost of production worth the outcome (Key and

Lycett 2017b, 751; Machin 2008, 762). However, even academics who support an argument

for functional selection in the production of handaxes recognise that this is unlikely to have

been the only factor in their shaping (Key and Lycett 2017a, 92; Lycett 2008, 2645; Mithen

2003, 762), as large flakes are as effective at cutting resistant material as similarly sized

handaxes (Key and Lycett 2017b, 751).

Perception and aesthetics

Ideas surrounding the development of perceptive skills and aesthetic understanding follow

similar models; the concept that Acheulean handaxe symmetry is a by-product of different

cognitive processes. Handaxes are one of the best examples of the development of spatial

cognition in early hominins as they had a clear system for the imposition of symmetry (Wynn

and Coolidge 2016, 205). This suggests that hominins, even as early as the individuals at

Kokiselei, were able to perceive spatial patterns, organise their actions in space, and

understand spatial relationships, in order to create symmetrical bifaces (Wynn and Coolidge

2016, 204). This was an important development for early hominins and sets them apart from

other primates. It demonstrates allocentric perception in individuals, meaning there is an

understanding of spatial positioning which does not change with a shift in vantage point,

which very much influences how an individual will perceive their own world (Wynn and

Coolidge 2016, 205). While in the archaeological record there is evidence of this

development through the appearance of handaxes at Kokiselei, 1.76 Ma, it is likely that the

symmetry in handaxes was merely a by-product of spatial perception evolving for other

purposes.

The symmetry in handaxes may not just be related to spatial perception, but also an

increase in perceptual awareness or bias. Perceptual bias is the concept that an individual is

inclined to create a certain object or shape because of a positive neurological feedback due

to the cognitive perception of it (Hodgson 2009, 196). The preference for symmetry could

come from a perceptual bias, as symmetry is often acknowledged before the conscious

recognition of an object. So this ability to perceive symmetry may have evolved to promote

the detection of objects more generally (Hodgson 2009, 196). Another theory from Hodgson

(2019, 242-243) suggests that an individual’s improving technological capacity would

produce a cognitive ‘surplus’ which is then directed at other concerns. This cognitive surplus

leads to an increase in perceptual awareness that, when coupled with repetitive rhythmic

actions, simulates cognitive procedures activated when creating patterns. However, there is

no evidence that Acheulean hominins had the capacity to create patterns, instead handaxes

indicate a precursor to this ability; a proto-aesthetic perception (Hodgson 2019, 244). The

cognitive surplus leads to a perceptual pleasure of reducing prediction errors and creates a

positive feedback from the aesthetic, symmetrical object, a reaction that is still observed in

modern humans from infancy (Hodgson 2019, 246).

Aesthetics, and the perception of aesthetics, are popular arguments for the symmetry in

Acheulean bifaces. The golden ratio is observed in a significant percentage of handaxes,

which shows that some proportions are highly controlled in bifaces and could be due to an

aesthetic sense (Gowlett 2011, 175). It has been shown through experimentation that if a

knapper only strikes at the most optimal platform, without considering future consequences,

an individual will create an elongated core with a bifacial edge. However, knappers invest

more time and energy to create an object that is pleasing, showing the ability for aesthetic

appraisal (Wynn and Berlant 2019, 283;293).

The development of spatial, aesthetic, or pattern perception may have evolved for

the success of early hominins in other aspects of their lives, but in the archaeological record

it is represented in the seemingly deliberate symmetry of Acheulean handaxes.

Social signalling

The most famous theory explaining the symmetry of Acheulean handaxes is the ‘Sexy

Handaxe Theory’. This model, conceptualised in Kohn and Mithen, 1999, posits that

handaxes were products of sexual selection and were used as reliable indicators of the

quality of potential mates for the opposite sex. Individuals who could create more

symmetrical handaxes were considered more suitable. This is one of many approaches that

relates symmetry to social signalling, often aligning more symmetrical handaxes with more

successful members of society.

Another of these theories is the ‘Trustworthy Handaxe Theory’, which argues that

instead of signalling for mating reliability, the production of handaxes indicated

trustworthiness to the group (Spikins 2012, 385). While the sexy handaxe theory relied on

the idea that handaxe production showcased the fitness of an individual, the trustworthy

handaxe theory instead suggests that production indicates a level of self-control required of

group members in early hominin societies (Kohn and Mithen 1999, 521; Spikins 2012, 385).

The basis for both theories is the concept of increasing group sizes in the Acheulean,

which require more scrutiny of their members in order to either choose a mate or root out

untrustworthy individuals. However, a broader perspective on how Acheulean handaxes

aided in larger groups is through the idea of social normativity.

Normativity refers to conventions and institutions within a human society, and often requires

prosocial behaviour (Shipton 2019, 155). Acheulean handaxes could be signals of

normativity as each assemblage seems to vary around an average type, with variability

between locale typology. This is exemplified by the handaxes found in Britain. The land was

abandoned and recolonised multiple times, with each occupational phase exhibiting distinct

biface types (Shipton 2019, 156). From this, it could be argued that each individual group

had their own slight variation of the handaxe in order to identify their members. When

looking on a global scale, the sexy or trustworthy handaxe theories are more appropriate, as

they explain the ubiquitous degree of symmetry, the abundance in the record, and the

unique outliers sometimes found (Mithen 2008, 766). However, on a local scale it is more

likely that, if these bifaces were social signals, they were signals for normativity and

indications of pro-social members of the group, due to their high cost and inter-site

variability.

Discussion and conclusion

The perspectives discussed above clearly apply to the concept of a handaxe that is most

familiar, one from the later Acheulean which is beautifully symmetrical and intentional. The

handaxes at Kokiselei 4 do not fit into this category. While they are more complex than their

Oldowan predecessors, and the precursors of intentionality and symmetry are apparent, they

may not be considered to have the intricacy to represent cognitive or social developments.

Cognitive developments are difficult to observe in the archaeological record and the

understanding of whether knappers at Kokiselei 4 had crossed a threshold of spatial and

aesthetic perception is limited by the lack of evidence. While the handaxe in Figure 1 does

meet the design features of an Acheulean biface, it is only vaguely symmetrical (Wynn and

Berlant 2019, 285), so it can be argued that the individuals at KS4 had not developed the

positive feedback from creating symmetrical visuals.

When examining them as possible social signalling devices, can it be argued that individuals

engage in high cost production processes that would indicate either fitness or self-control?

The fact that there is evidence for other large cutting tools at Kokiselei 4, such as picks and

unifacial axes (Lepre et al. 2011, 82), would indicate that there wasn’t necessarily a need for

the more complex symmetrical bifaces. This would show that they have social value, as from

a functional perspective they are more high-cost to produce than the pay-off, unless there

was a social reward for the effort. Therefore, even in their unrefined form, the Acheulean

handaxe could be used for social signalling, although in a more limited way than in later

examples. More experimental work would need to be done on the production cost of crude

handaxes compared to competent handaxes to further evaluate this hypothesis. It can be

argued that they were normativity symbols from their inception at KS4 and aided in

identification of group members as groups began to encompass non-kin members. There

would have been a distinction between Oldowan groups and Acheulean groups, and the

handaxe may have been used as a signaller of membership, and therefore prosociality, even

in its most rudimentary form.

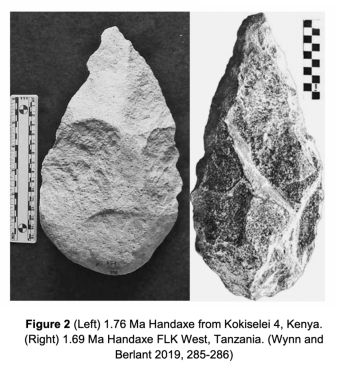

It is most likely that at this early stage in the Acheulean, when handaxes appeared alongside

Oldowan flake technologies, that they had a mostly functional purpose that then developed

into a social device at a later stage. Because of a lack of intentionality in shaping, the KS4

assemblage indicates only a technological advancement, with the use of a hammer and anvil

technique, and the bifaces found there are only a prototype for the fully socially and

cognitively integrated handaxes in the later Acheulean. When comparing this assemblage to

others in the area, there is a stark contrast between KS4 and FLK West, in Tanzania, which

is dated to only a few thousand years later at 1.69 Ma. The symmetry in the handaxe found

at FLK West is intentional and the knapping skills appear more advanced, as can be seen in

Figure 2 (Diez-Martín et al. 2015, 6; Wynn and Berlant 2019, 285). This demonstrates that it

did not take long for the handaxe to become artefacts that could have been used in the

social sphere, or that could be interpreted as having been subjected to aesthetic appraisal.

In conclusion, it is likely that Acheulean handaxe symmetry was not only functional, but also

a by-product of other cognitive developments, and used in the social sphere for signalling. It

is likely that the initial variability in tool form that gave rise to the acheulean handaxe was

due to the introduction of different tasks that required different tool functions. However, it

cannot be denied that there is likely a perceptual bias that caused the symmetrical shape to

be apparent even in its earliest form at KS4. It is more difficult to assess what social nature

that handaxe then adopted, but the normativity argument best explains how it could have

been used even in the proto-Acheulean. The earliest examples of handaxes at Kokiselei 4,

while not showing very high levels of intentionality, demonstrate that there is still an attempt

at symmetry, which would indicate that the symmetry of the handaxe has been a key

component of the tool type since its inception.

![Figure 1 ref: A, Lancaster. (nd.) Early Medieval Wales. Available at: viking-5-wales-vikings-on-the-coast.jpg [accessed 17/02]](https://theposthole.org/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/article_thumb/public/articles/506/Figure%201%20%281%29.jpg?itok=22FvdRE7)