Is it just me or has there been a lot of archaeology in the news lately? Taking the BBC News website as one example, during the past month there has been a variety of articles on archaeological discoveries, from ‘Desert finds challenge horse taming ideas’ to ‘‘Amazing’ treasures revealed in Dartmoor Bronze Age cist’.

I suspect this change is due to the recent announcement that human remains found beneath a car park in Leicester have been concluded to be those of Richard III. If it is true that this particular discovery has encouraged the media to turn greater attention to other findings in the world of archaeology, I believe it is far from commendable but actually rather sad.

Most archaeologists have long acknowledged that linking the public with the past is highly beneficial to communities and the academic profession. However, there has never seemed to be a definite conclusion as to the best ways of enabling that to happen. My opinion is that ‘post-Richard III’ media interest in archaeology will pass almost as quickly as it arrived in Leicester last year. The articles in this issue of The Post Hole should remind us that it is local people - including students, lecturers and museum curators - who play the greatest part in linking the public with the past.

Flo Laino reports about her experiences of re-establishing the toy exhibition in the York Castle Museum as a side-project to a blog she maintained for a Visual Media module in her undergraduate archaeology degree. Laino provides a fascinating insight into the balance between family engagement and intellectual insight that archaeologists and museum curators aim to reach in museum exhibits. It is encouraging that York Castle Museum actively encouraged the contribution of other people’s ideas in improving their exhibition. Laino convinces us that more museums should follow a similar strategy to improve their impact on visitors.

Navid Tomlinson, Sarah Drewell and Rachel Mills review a small selection of the papers from the Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG) conference at the University of Liverpool last December. The papers that they review reinforce Laino’s own observation that a lot of archaeology is as involved with the local community as it is with understanding the past. At the end of his review, they ask us whether TAG conferences are becoming less theoretical. I would suggest that it is archaeologists’ growing realisation that people are central to the acquirement and utilisation of information about the past that is of prime interest to archaeological theorists today. In part, it requires theory for archaeologists to understand the implications of people on the academic discipline.

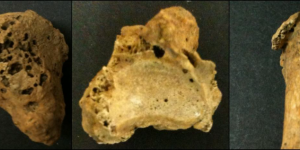

Tatiana Feuerborn explores the influence that people’s subjective definitions of arbitrary classifications can have on osteological analysis of archaeological remains. Through analysing the demographic of people with degenerative joint disease in medieval Malmesbury for her undergraduate dissertation, Feuerborn explains how she has been exposed to the limitations in the typical classification of remains exhibiting this disease. Feuerborn calls on osteoarchaeologists to follow a more precise framework in identifying degenerative joint disease to allow the exact severity of its symptoms to be found more consistently.

Katie Rawlinson guides us through the ethics of primatology studies and encourages us to contemplate on whether existing procedures in this academic field are truly of benefit to archaeological interpretations and the welfare of the animals that are studied. Rawlinson examines the relationship between people and animals in primatology and concludes that the influence of the former group on the behaviour of the latter group may make interpretations about human evolution inherently flawed.

Finally, in a special feature, Nicky Milsted, Communications Officer of the Young Archaeologists’ Club (YAC), a youth organisation run by the Council for British Archaeology (CBA), explains the academic and community benefits of various initiatives of the CBA for archaeology in the UK. This follows an article in Issue 26 by Emily Hellewell who introduced us to the contribution of University of York students and the Young Archaeologists’ Club in delivering activities which familiarised children with what life may have been like in the Mesolithic period.

It is important that further collaborations occur between students, organisations, museums and other people and bodies with an interest in the past. If they do not, the public’s connection with archaeology will be at stake and what a terrible shame that would be, both culturally and academically.

That summarises Issue 28. Most of the team have spent very little time working for The Post Hole lately because of imminent dissertation and essay deadlines. We look forward to paying much greater attention to advertising the journal to more students, academics and members of the public over the coming months as our schedules start to become clearer once again.

We are especially keen that students at universities across the UK and indeed the world continue to share their innovative research and views on the past through The Post Hole. If you are interested in writing for The Student-Run Archaeology Journal, please contact Alison Tuffnell at submissions [at] theposthole.org for enquiries and submissions. For the latest news about The Post Hole, including Issue 29, follow us on Facebook and Twitter (see back cover).

Enjoy reading!

David Altoft

(Editor-in-Chief of The Post Hole - david.altoft [at] theposthole.org)