Throughout ancient Mesoamerica, caves were perceived as important features of the sacred landscape (Brady and Prufer 2005). Caves were accompanied by a rich set of images and mythic narratives, detailing acts of creation and the emergence of human beings from the underworld (Heyden 2005). Although the origin of these narratives has often been associated with the cave symbolism present in the Olmec-style art of the Formative period (c. 1500-500 BC) Gulf Coast lowlands (Grove 1973; Scott and Brady 2005), the human use of caves in Mesoamerica extends well into the Archaic period (c. 8,000-2,000 BC) (Smith 2005). Archaic period rock art in Mesoamerica, however, is attested at only a handful of sites: the Cauadzidziqui rock shelter (Guerrero, Mexico), Santa Marta cave (Chiapas, Mexico), Loltun cave (Yucatan, Mexico), the El Gigante rock shelter (Honduras), and the Espirito Santo cave (El Salvador). This identification is based on the presence of hand prints, rudimentary anthropomorphic figures, and the presence of abstract geometric art (Gutiérrez 2008; Gutiérrez and Pye 2008; Haberland 1972; Künne and Strecker 2003; Velázquez Valadez 1980).

In this brief report, I present evidence for the existence of cave imagery among some of the non-Olmec, possibly Late Archaic period (c. 2000 BC), rock paintings of Oxtotitlán cave in Guerrero, Mexico (Figure 1). The use of cave symbolism at Oxtotitlán, is comparable to the images of caves found on art works from later periods of Mesoamerican history, suggesting that these rock paintings may be one of the earliest portrayals of this common trope in Mesoamerican art.

Archaic Period Rock Art and the non-Olmec Rock Paintings of Oxtotitlán Cave

As noted previously, there have been relatively few examples of Mesoamerican rock art attributable to the Archaic period (Gutiérrez 2008; Künne and Strecker 2003). Most archaeological work has been concerned with the content and technique of Archaic rock paintings due to the lack of direct chronological measures, and the ambiguity of archaeological associations to cultural materials with established chronologies (Coladán 1995). In eastern Guerrero, however, the situation has been somewhat ameliorated by the recognition of an Olmec-style painted mural superimposed on top of much simpler monochromatic rock paintings at the Cauadzidziqui rock shelter, near the Oaxaca-Guerrero border (Gutiérrez 2007). Since the Olmec-style rock paintings of eastern Guerrero have been dated to the Middle Formative period (900-500 BC), based on iconographic comparisons with the sculptures of La Venta, Tabasco (Grove 1970a, 1970b), it has been convincingly argued that the abstract geometric paintings that were superimposed by the Olmec-style paintings probably date to the Late Archaic period (c. 2000 BC) (Gutiérrez and Pye 2008). Similar monochromatic paintings occur at both Oxtotitlán cave and Juxtlahuaca cave in central Guerrero (Gutiérrez 2008, 80), suggesting that they can be stylistically associated with the Late Archaic rock art of Cauadzidziqui.

Although it is best known for its array of Middle Formative period Olmec-style black paintings and polychromatic murals (Grove 1970a, 1970b; Lambert 2012), Oxtotitlán also boasts a number of red rock paintings in its south grotto that are not as easily attributed to the Formative period. These figures have typically been divided into three panels, known as the Area A, B, and C paintings respectively (Grove 1970a, 1970b). The Area A rock paintings are composed of a number of geometric elements including curvilinear lines, triangles, cruciform motifs, and concentric circles (Figure 2). While it is likely that the majority of these simple red figures date to the Late Archaic period, as do their counterparts at Cauadzidziqui, some of the compositions in this panel, such as Painting A-3, contain elements – e.g. goggle-shaped eyes and protruding fangs – reminiscent of Classic and Post-classic period depictions of rain gods (Grove 1970a, 77, 1970b, 26). Only one of these red cave paintings, Painting A-1, appears to date to the Middle Formative period, and may have served as a tepetl place-sign (Lambert 2013).

Located to the right of the Area A rock paintings, the Area B rock paintings appear to consist of a series of zigzag lines, triangles, arrows and other linear elements (Grove 1970a, 75-77, Fig.24) (Figure 3). Very little attention has been paid to these red geometric figures. One exception is the naturalistic portrayal of a deer identified as Painting B-2. The deer in this rock painting is rendered in a leaping stance and is accompanied by a series of red lines forming a box around the head of the deer. To the left of the deer, there appears to be a very weathered human figure. Grove (1970b) claims this scene might have served as the basis for rituals associated with hunting magic.

Situated to the right of the Area B panel, the Area C rock paintings are found primarily in the crevices near the ceiling of the cave, towards the centre of the south grotto (Grove 1970a, 76-77, Fig.25). This cluster of rock paintings consists of simple geometric designs, such as curvilinear elements, comb-like motifs, and a schematic, possibly avian, figure formed by several triangles (Figure 4).

The Cave Imagery in the Area B Rock Paintings of Oxtotitlán

Despite their apparent randomness, a careful examination of the geometric and zoomorphic designs that comprise the Area B rock paintings reveals that this group of images forms a cohesive picture. Using cave symbolism in later Mesoamerican art works as points of comparison, I suggest that the Area B rock paintings of Oxtotitlán portray the cave as a place of emergence and a source of fertility.

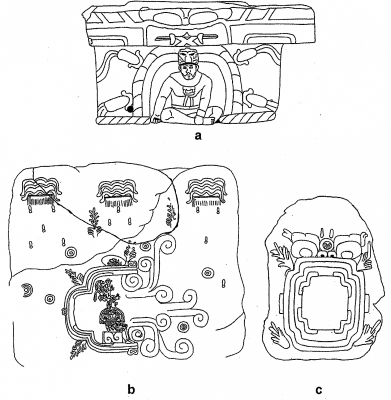

In terms of their overall appearance, the Area B rock paintings seem to be organised along two bands of triangular designs (Figure 5). The top band of triangles appear to delimit the relatively flat top of the mountain on which Oxtotitlán is located; while the other band of triangular motifs form a baseline, possibly portraying the cliff face of the cave. Similar bands are found on thrones in Olmec-style art, such as Altar 4 from La Venta, Tabasco, and are used to represent the surface of the earth in relation to cave-like openings in the sculptures (Grove 1973, 131) (Figure 6a). Highly stylized versions of such bands are also observable in the quadripartite depictions of the underworld as a cave in the low-relief carvings of Chalcatzingo. (Figures 6b-c).

A small semi-circular opening indicating the cave itself, is represented on top of the baseline formed by the lower band of triangular motifs. The negative space representing the opening is bordered by diamond-shaped designs, and features the outline of an anthropomorphic figure in the centre of the space. This manner of representing caves is quite common in ancient Mesoamerican art, and is seen in the quadripartite imagery of Chalcatzingo Monument 9 (Figure 6c). The diamond-shaped designs may also be precursors to portrayals of the earth as a turtle-like zoomorph in Maya art (Stone 1995, 24-27). Among some of the more well-known examples of this trope are the Late Formative monuments designated as Tak’alik Ab’aj Altar 48 (Figure 7a) and Izapa Stela 8 (Figure 7b), as well as Late Classic codex-style polychrome vessels depicting the resurrection of the maize god from a turtle carapace (Quenon and Le Fort 1997, Figs. 12, 27, 28, and 30) (e.g. Figure 7c). Above this putative cave opening, there are a series of diagonal meandering lines and a large conglomeration of red paint. These may represent some of the geological features found near the cave, such as the exposed travertine cliff-face above the cave opening (see Figure 1). Underneath the baseline of triangles, the “slopes” of the mountain leading up to the cave are likewise portrayed in the form of zig-zags and meandering lines. At the bottom of the rock painting, two animal figures are recognizable on these “slopes”, and one appears to have antlers or horns. While more commonly addressed through depictions of foliage in later Mesoamerican art (see Figures 6 and 7), it is possible that the representation of caves as sources of water and food was achieved through the portrayal of fauna during the Late Archaic period at Oxtotitlán.

Conclusions: Oxtotitlán and Cave Imagery in Mesoamerica

This paper has argued that the non-Olmec geometric designs found among the Area B rock paintings of the South Grotto of Oxtotitlán represent a Late Archaic period portrayal of a cave. If this interpretation of the imagery in these rock paintings is correct, then the non-Olmec rock art at Oxtotitlán may represent one of the earliest depictions of a cave in Mesoamerican art, and could provide scholars with a better understanding of one of the most potent motifs in Mesoamerican mythology. Previous research on the Mesoamerican cave trope has demonstrated that these geological features were associated with a number of closely related cosmological relationships linking agricultural production, rainfall, and ancestor veneration with important mythological events (e.g. the earth’s creation, the origin of humanity, the residence of the gods, and the origin of the sun and moon) (Heyden 2005). Over time, the meanings linked to Mesoamerican cave imagery were expanded to include references to ancestral rulers and important lineage members, and caves became important places of worship and pilgrimage (Brady and Prufer 2005). This study of the non-Olmec rock paintings from Area B at Oxtotitlán, however, indicates that the portrayal of caves as places of emergence and as sources of food and water may be some of their earliest symbolic associations, and may form the cosmological foundations of later Mesoamerican views of caves.

Bibliography

- Brady, J.E., and Prufer, K.M. (2005). ‘Introduction: A History of Mesoamerican Cave Interpretation’ in Brady, J.E., and Prufer, K.M. (eds.) In the Maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican Ritual Cave Use. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 1 -18.

- Coladán, E. (1995). La gruta del Espíritu Santo (El Salvador). Tendencias. 3 (45), 40-42.

- Grove, D.C. (1970a). Los Murales de la Cueva de Oxtotitlán, Acatlán, Guerrero. Informe sobre las investigaciones arqueológicas en Chilapa, Guerrero, noviembre de 1968. Serie Investigaciones, * * * Núm. 23. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia.

- Grove, D.C. (1970b). The Olmec Paintings of Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero, Mexico. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology, No. 6. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks/Trustees for Harvard University.

- Grove, D.C. (1973). Olmec Altars and Myths. Archaeology. 26 (3), 94-100.

- Grove, D.C., and Angulo, J. (1987). ‘Catalog and Description of Chalcatzingo’s Monuments’. In Grove, D.C. (ed.) Ancient Chalcatzingo. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 114-131.

- Gutiérrez, G. (2007). Catálogo de Sitios Arqueológicos de las Regiones Mixteca-Tlapaneca-Nahua y Costa Chica de Guerrero. Mexico: CIESAS.

- Gutiérrez, G. (2008). ‘Four Thousand Years of Graphic Communication in the Mixteca-Tlapaneca-Nahua Region’. In Jansen, M., and van Broekhoven, L.N.K. (eds.). Mixtec Writing and Society. Amsterdam: KNAW Press, pp. 67-103.

- Gutiérrez, G., and Pye, M.E. (2008). El graffiti estilo olmeca del abrigo rocoso de Cauadzidziqui, Ocoapa, Guerrero. Oxtotitlán 3, 20-26.

- Haberland, W. (1972). The Cave of the Holy Ghost. Archaeology 25 (4), 286-291.

- Heyden, D. (1975). The Cave under the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan. American Antiquity. 40 (2), 131-147.

- Heyden, D. (2005). ‘Rites of Passage and Other Ceremonies in Caves’. In Brady, J.E., and Prufer, K.M. (eds.) In the Maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican Ritual Cave Use. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 21-34.

- Lambert, A. (2012). Three New Rock Paintings from Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero. Mexicon 34, 20-23.

- Lambert, A. (2013). A Possible Place-Sign (Toponym) from Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero, Mexico. The Post Hole, 27, 17-28.|

- Norman, V.G. (1973). Izapa Sculpture, Part 1: Album. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 30. Provo, Utah: New World Archaeological Foundation, Brigham Young University.

- Quenon, M. and Le Fort, G. (1997). ‘Rebirth and Resurrection in Maize God Iconography’. In Kerr, N. and Kerr, J. (eds.). The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases by Justin Kerr, Volume 5. New York: Kerr Associates, pp. 884-902.

- Schieber de Lavarreda, C. and Orrego Corzo, M. (2009). ‘El descubrimiento del Altar 48 de Tak´alik´ Ab´aj’. In Laporte, J.P., Arroyo B. and Mejía, H. (eds.). XXII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2008. Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, pp. 456-470.

- Scott, A.M. and Brady, J.E. (2005). ‘Formative Cave Utilization: An Examination of Mesoamerican Ritual Foundations’. In Prowis, T.G. (ed.) New Perspectives on Formative Mesoamerican Cultures. British Archaeological Reports, International Series, No. 1377. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 147-158.

- Smith, B.D. (2005). Reassessing Coxcatlan Cave and the early history of domesticated plants in Mesoamerica. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (27), 9438-9445.

- Stone, A.J. (1995). Images from the Underworld: Naj Tunich and the Tradition of Maya Cave Painting. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Stone, A.J. and Künne, M. (2003). ‘Rock Art of Central America and Maya Mexico’. In Bahn, P.G. and Fossati, A. (eds.). Rock Art Studies: News of the World 2. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 196-213.

- Velázquez Valadez, R. (1980). Recent Discoveries in the Cave of Loltun, Yucatán, Mexico. Mexicon, 2, 53-55.