Context

A number of metrics for the archaeological sector are recorded in ‘Profiling the Profession’, a series of reports produced at five-year intervals on behalf of the CIfA – most recently in 2012/13 by Landward Research Ltd (Aitchison & Rocks-Macqueen, 2013). These surveys identify the archaeological workforce, their roles, salaries, qualifications, the status of skills in the workforce, and the availability of training through employers. What these reports fail to capture is what commercial units and other employers expect when hiring for an ‘entry-level’ position - a job for which candidates with no previous paid employment in archaeology are considered.

This survey was conducted ahead of a workshop at Durham University in May 2015. It was designed to provide data, rather than anecdotal evidence, to help current undergraduates understand how to maximise their employability. When reading the results, the importance of changing economic and governmental circumstances on the employment market must be remembered.

The survey instrument

The survey format facilitated comparison between responses from different parties, while also allowing for more extended, detailed answers. Primarily, it assessed the degree to which certain skills, qualifications, or experiences would influence the chance of the applicant being hired for an entry-level position. A Likert-scale was used, by which responses were translated into a score from 0 to 10, with higher ratings representing a more positive impact on the application. This was supplemented by open response questions providing an opportunity for explanation and further detail.

The areas investigated in the survey were academic experience, including specialist skills such as osteoarchaeology; fieldwork experience; professional experience, including work outside archaeology; application skills; qualifications and memberships; and other knowledge and skills related to the heritage sector. The survey’s final questions established the company’s size, frequency of hiring over the last three years, willingness to hire recent graduates, and availability of training.

130 archaeological employers, drawn principally from the British Archaeological Jobs Resource, were contacted in March 2015. These were mainly commercial fieldwork units, as well as County Council teams, archaeological trusts, research companies, and prospection companies. Employers from museums and educational services were not contacted. The survey was offered initially over the telephone, and this proved to be the preferred method of response for those employers that took part. However, in several cases, units requested a written version of the survey, which was sent via email. This format was also sent to those employers who could not be reached by telephone; these responses from the written format were not distinct from those received by telephone.

Two companies declined to participate as a matter of company policy, while three were no longer trading. Ten companies had no entry-level archaeological employees, with no intention to hire any in the foreseeable future, and were excluded. In total, 40 employers returned surveys, of which 39 were in a suitable format for analysis, giving a rate of return of 30%. This exceeds the 10% sample size normally required to draw meaningful conclusions about a population, as well as the expected minimum of 30 cases.

The survey included several questions aimed at establishing the size of the current market for hiring entry-level staff, and the frequency at which these positions become available. This was also intended to permit investigation of whether hiring priorities are linked to either the size or hiring frequency of the company.

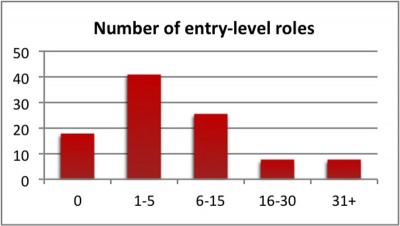

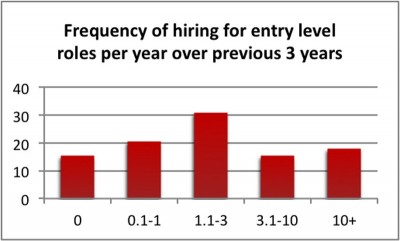

The average number of entry-level positions with each company at the time of the survey, including casual staff, was 11.14, although this varied widely between units. The largest proportion of units, 41%, had between 1 and 5 entry-level positions, while 18% had none at all (see figure 1). Recruitment for these positions averaged 10.06 staff per year between 2012 and 2015, including casuals. 36% of units hired less than once per year, with another 31% recruiting between 1 and 3 new staff annually (see figure 2).

Results of the research: Likert-scale responses

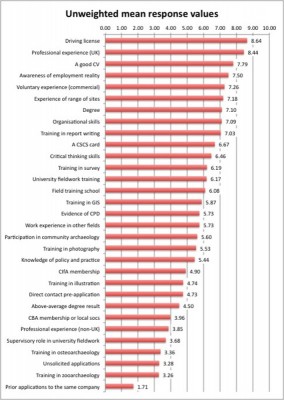

Overall, the respondents rated non-academic skills and experiences significantly higher than academic ones. Four of the six most highly valued qualities related to experience and understanding of professional archaeological employment in Britain, as shown in figure 3. Previous experience in professional archaeology was rated highly at 8.44, followed by an awareness of the reality of work in commercial archaeology. Voluntary experience with a commercial unit, and experience of a range of archaeological sites were also valued above 7.00. The remaining two top qualities were possession of a driving license – the most highly rated quality of all – and submitting a good resume, the third most influential factor.

Holding a degree in archaeology was considered important – scoring 7.10 overall, and ranked as the seventh most helpful quality for finding employment. However, having a grade above 2:1 was not seen as significant. Undergraduate training in specific skills was given lower ratings – with five scores below 6.00. This reflects the expectation that new applicants will require company-specific training regardless of the content of their undergraduate course. The exceptions to this were training in report writing (7.03), and survey and prospection techniques (6.19). Training in GIS applications and photography were rated as helpful skills which were not expected in candidates.

Fieldwork in non-commercial environments was generally rated poorly. While gaining a university degree in archaeology was considered important, experience of university fieldwork training was rated at 6.17. Some respondents commented on the variability of this training between institutions, although several suggested that this experience was considered more valuable if they were familiar with the staff or department involved. Holding a supervisory position during university field training would not greatly improve the strength of an application. University training did score more highly than other schemes, such as participation in a field training school, or community project. Perhaps surprisingly, experience of professional archaeology outside the UK scored only 3.85.

Factors associated with a candidate’s application, other than the presentation and content of their CV, were not considered influential. Having made previous applications to the company was the lowest rated of all the factors, at 1.71. Making speculative applications for employment was considered somewhat advantageous, as was contacting an employer to discuss an advertised position or ask for further information.

Holding a CSCS (Construction Skills Health and Safety) card was rated as a valuable quality, if not an essential one, scoring 6.67. Membership of archaeological societies was rated somewhat lower, with the CIfA at 4.90, and the CBA or local societies at 3.96. Transferrable professional skills were received well, however, with both organisational skills and critical thinking rated highly if demonstrated with evidence in a CV or covering letter. Having a record of continuing professional development or knowledge of policies and practices in heritage management were not expected but were considered beneficial. Finally, having employment experience in general, even if outside archaeology, was rated at 5.73.

Open responses

25 of the employers felt able to quantify the length of non-commercial fieldwork experience they expected candidates to have gained before applying, with an average of 12-13 weeks of fieldwork experience. Six companies reported a variation of ‘quality over quantity’, and indicated an interest in where the experience was acquired, the reputability of the body organising the fieldwork, and the range of experiences gained. Several of these companies identified referees as a way of assessing this. Five companies considered non-commercial fieldwork to be largely irrelevant, beyond showing interest and physical capability, while two more simply stated ‘as much as possible’.

Unsurprisingly, a number of units identified the value of experience in construction or engineering (6 citations), museum work or work with a historical theme (4 citations), and especially work related to geographical or geological survey (10 citations). Four units made references to the army, outdoor, or physical occupations. Other sectors referenced included education, outreach, communicative or creative industries, computer-based work, photography, environmental work, accounting, research, and data handling.

Another open-response question was included to expand on the question ‘How important is a good CV’. 16 different features of a ‘good CV’ were listed between the 39 units, although a small number were cited frequently. 22 employers defined a good CV as, ‘concise’, or ‘succinct’, containing enough detail without becoming wordy, with 17 wanting a structured CV. 15 employers noted that CVs should be tailored to the job advertised, by focussing on relevant skills and referring directly to the specification. Other qualities expected were accuracy of spelling and grammar (11 citations), the highlighting of key skills (8 citations), honesty and accuracy (6 citations), and the inclusion of sufficient detail to give a meaningful understanding of the applicant’s experience (6 citations).

Finally, suggestions were requested for other important factors that had not been listed in the survey. Several of the responses to this question related to CVs, and were merged into that data. The range of responses was again broad, with 18 different categories of answer, and none being given by more than four different employers. These were having good references, demonstrating a sense of humour, and living in the local area or specifically showing willingness to move for the position. Willingness to learn and physical fitness each received 3 mentions. Other qualities mentioned as those employers might look for in an application included intelligence, a willingness to work away, sector-specific knowledge, and social media skills.

Training Schemes

This section of the survey was included at the request of the CIfA, and asked respondents to state whether they offered training to staff in entry-level positions, and if so, whether that training was through a formal programme, informal but with identified targets, or informal without targets.

Only 5 of the 39 companies offered no training for entry-level staff. These five were smaller than average, and four were also less active, or not active at all, in the hiring market. Among the 34 employers offering training, the vast majority provided informal schemes, with only four stating that they also provided access to some formal graduate training alongside this. However, more respondents organised some or all of their informal training with identified targets or outcomes (20) than without (14).

There was some correlation between the size of the company and the formality of training provided, with smaller companies (0-5 entry level staff) generally offering informal training without targets, or no training at all. Larger employers (6+ entry level staff) all provided some form of training, with 75% providing formal training, or informal training with identified targets. Three of the four employers offering formal training fell into the 6-15 entry-level staff category.

Weighted results

The survey showed significant variation between employers in the number of staff taken on per year in entry-level positions, with some taking on no new staff in the last three years, and one hiring approximately 150 times per year. Consequently, weighting each employer equally does not accurately represent the job market perceived by applicants. To counteract this, the data was weighted according to the hiring frequencies of each company, using the categories they self-selected.

The weighted results, shown in figure 4, were broadly similar to the unweighted results, with nine of the same qualities selected in the top ten. The tenth, evidence of organisational skills, was replaced by undergraduate training in GIS applications. However, there were some noticeable changes in both the absolute rating for each skill, and their relative rankings.

Professional experience continued to dominate the most highly rated qualities, with all three (professional experience, voluntary experience, and awareness of the realities of employment) even being rated slightly more highly. However, experience of a range of site types was considered less important. This, together with having a good CV, was overtaken by having a degree.

Undergraduate-level training in GIS applications, photography, and survey techniques were rated somewhat more highly in the weighted results. However, undergraduate training in illustration, zooarchaeology, and osteoarchaeology were given noticeably higher ratings, although they remained lower in the relative ranking of skills and qualifications. Having a good degree was rated more strongly, at 5.57.

Membership of the CIfA was seen a more positive light in this data, at 6.17, while contacting the advertising company to discuss the position also gained noticeably (5.72).

Experience outside professional archaeology was markedly less valuable – university fieldwork training was ranked 11 places lower in the weighted data, with community projects regarded similarly. Work experience in other fields was also rated significantly lower, at 4.03.

Interpretation

The weighted results reflect to a greater extent the priorities of employers that hire more frequently. These employers seem to place less significance on participation in university fieldwork, community archaeology projects, and work experience outside archaeology – although still acknowledging that they have a positive influence on a candidate’s employability. At the same, modules offering training in specific skills at undergraduate level are received more positively, as are both holding a degree in archaeology, and gaining an above average degree result.

Taken together, this suggests that those employers who hire more frequently prefer skills and experiences that can be clearly identified from a CV, in particular, those which have a measurable outcome, and which are comparable with those of other candidates. This may be because the increased recruitment rate reduces the time these units can spend investigating and assessing the quality of fieldwork training. In contrast, academic results and the ability to pass a given training module represent a readily comparable measurement of candidates, while skills-based modules are easily identified from a CV or application form. This interpretation is supported by the comments from participants that university and community projects vary in the quality of experience and training provided. Unless they were personally familiar with the projects or the staff involved, these respondents assumed that the impact on the candidate was minimal.

In contrast, submission of a well-presented CV saw a relative drop in position. This may be due to the use of application forms in many companies, which require statements assessing skills in relation to the job specification, reducing the importance of the CV. Finally, the importance of references should not be underestimated in showing how effectively the candidate has learned from the experiences listed on a CV. Respondents indicated that they felt able to judge the value of references that came from an employer who was known to them.

Conclusions for current undergraduates

The results emphasise the value of practical experience with professional companies. The majority of undergraduate archaeology courses require 2-6 weeks attendance at a training dig, but placements with commercial units are rare. Gaining this experience therefore requires effort on the student’s part, but the survey suggests it significantly increases employability.

Academic success, beyond completing a degree, was not considered as helpful, and skills generally associated with specialist staff, such as osteoarchaeology, are not expected in entry-level positions. However, it should also be noted that taking these modules may be useful for access to postgraduate courses that lead to work in those specialist roles.

Having a driving license was considered important by most employers, and can be undertaken alongside degree studies. Similarly, most universities offer training in CV and application writing skills.

Finally, several employers mentioned that they pay special attention to applications from archaeologists they have personal experience of working with, including as temporary or voluntary staff. Attending voluntary projects gives students the chance to experience a range of different site types, meet potential future employers and demonstrate their fieldwork proficiency – as well as their general character, considering that 10% of the responding companies value a good sense of humour.

Conclusions for recent graduates

Working voluntarily with commercial units is a good way to gain experience, and is rated by employers almost as highly as paid employment, although this may not be a financial possibility for recent graduates. Furthermore, the use of volunteers has wider implications for the number of paid positions available in the job market, as recognised by several respondents.

Working outside of archaeology increases employability, over those with no work experience at all, which is helpful for graduates who need to earn while looking for work. Several companies identified a need for applicants to show a continuing interest in the field, suggesting that at least some voluntary involvement in archaeology, such as in evening or weekend activities, is a good idea. Courses in specialist skills, although sometimes expensive, may also be worthwhile.

Lastly, one area where graduates can improve their employability is in their application skills – producing a good CV, and tailoring their application to the job specification. Respondents also recognised contacting the company to discuss the position as a positive trait, provided that the candidate had a meaningful question to ask.

Useful resources

The British Archaeological Jobs Resource – www.bajr.org

BAJR is an indispensable source for information on jobs and training courses, not only for those aiming to work in archaeology, but those already employed. Run by a professional archaeologist, BAJR also has an interest in workplace conditions and professional development. The group has an active Facebook presence.

The Council for British Archaeology – www.archaeologyuk.org

The CBA is a major piece in the mosaic of regional and specialist societies, and amateur archaeology organisations across the country, and also produces the ‘Archaeology’ periodical. The website has contacts for a range of training courses and volunteer experiences, as well as funding opportunities. The CBA also organises a series of workplace training schemes that are an alternative route into professional employment.

The Chartered Institute for Archaeologists – www.archaeologists.net

The CIfA is the most widely recognised professional body representing archaeologists in the UK, and sets targets for both employers and employees in professional training and standards, and employment conditions. The CIfA produces a fortnightly jobs bulletin for members, also covering heritage management and academia.

References:

- Aitchison, K and Rocks-Macqueen, D. (2013). ‘Archaeology Labour Market Intelligence: Profiling the Profession 2012-13’, available at <http://www.landward.eu/Archaeology%20Labour%20Market%20Intelligence%20Profiling%20the%20Profession%202012-13.pdf> Page consulted 21/04/2015

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Dr Sarah Semple for editing the report, and Kate Geary for reviewing the survey instrument. This report will also be made available on BAJR.org.