Abstract

Many historic house museums in the United Kingdom have had a long and tumultuous history before coming into the public realm. This essay argues that the majority of approaches to interpretation taken at these properties represent variations along a similar theme, that of ‘telling the story of the house and its occupants’ through the material culture of objects, furnishings and where possible, the records. What is often missing is the social and political relevance of these houses and their stories to the world today, how their links to (often deeply controversial) past practices are reflected in contemporary society. Using case studies from the United States, and in line with Sandell’s (2007, 5) view that museums have the “potential to function as an agent of social change”, I argue that these properties are uniquely situated to probe and explore these issues. Therefore curators have an obligation to their communities and the public at large to develop their offering and to act as agents of positive change in society.

Historic house museums - a rich and unique resource

Historic house museums, as all museums, have an obligation to serve their public in all its forms (Benton and Watson, 2010, 129) which presents curators with a plethora of challenges and opportunities as they strive to meet this responsibility. The premise of this essay is that historic house museums, in particular, have an obligation to drive contemporary social change. As Tilden (2007: 35) argued, “the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction but provocation”. Many historic house museums, due to the nature of their histories, represent a uniquely fitting environment in which to encourage dialogue and the exchange of ideas around associated contemporary subjects that are often controversial and sometimes emotionally challenging. Raising social awareness through critical engagement with the subject matters covered in the interpretation should play a central part in the role of historic house museums.

By their very nature as a former place of dwelling, house museums are instantly intelligible to visitors on the most primal level (Donnelly 2002: 3) and thereby enjoy an innate advantage over many other types of museums. This is of fundamental importance and imbues historic house museums with a rich emotional connection on which to draw. However, the curators of historic house museums have been traditionally conservative in their approach to interpretation. The majority of their efforts have focused on telling heteronormative narratives of the male socio-elite in a way that at best minimises and at worst ignores the social history of whole segments of society, nullifying the complex web of influences and relationships between them all (Oram, 2011). This bias in interpretation focus is what Smith (2006: 30) identified as the Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD).

Defining the interpretive approach to take in these properties however, is by no means a straightforward procedure, as Hughes (2008: 897) explains:

“These are spaces which have evolved and continue to evolve in response to successive inhabitants, rather than museum objects removed from their context, and great sensitivity is required to acknowledge and address these intensely personal values within the pluralist framework of culturally constructed heritage values”.

The approaches taken by historic house museums can be grouped into two main categories; traditional and theme based presentation and interpretation.

Traditional approaches to interpretation

Young (2007: 59) has identified a range of genres of historic house museums that fall within the broad category of ‘traditional approaches’: “Houses become museums as monuments to heroes, monuments to collectors, monumentalized specimens of design or innovation, monumental commemoration and/ or interpretation of historic events and associations”. It could be said that on the whole, the majority of historic house museums in the U.K. today are presented through one of these traditional genres. These approaches have been criticised by Smith (2006: 30) for reinforcing the AHD through the emphasis on the preservation of the buildings, objects and stories of the elite social classes over that of vernacular architecture and the stories from those of lower socio-economic groups. Consequently, the picture of the white, male head of the house as a historical figure of leadership has become the standard national heritage identity in England (Smith, 2006: 115).

More recently the AHD has begun to be challenged by an increase in the number of vernacular properties being preserved, restored and opened to the public as house museums, a good example of which are the Birmingham back-to-back terraced houses, built around a central communal courtyard. Here the interpretation focuses solely on the working class people who lived there using a ‘stop the clock’ approach to present the homes and shops frozen as time capsules ranging from the 1840s through to the 1970s (National Trust, n.d.). However, with the majority of historic house museums in the U.K. still squarely concentrated on the properties and past lives of the social elite, there is clearly an imbalance of representation.

An argument can be made that these more traditional approaches to presenting historic houses, whether applied to properties of the social elite or of the vernacular kind, are based predominantly on the practice of transferring knowledge from the museum to the visitor. The house museum is visited to learn about history, rather than through history. The experience, by its very nature, is constructed in a way that does not easily promote a deeper level of learning or engagement beyond the appreciation—in the case of the house museums of the social elite—of a fine building full of fine things and set in a fine landscape. While appreciation of this sort can be a goal in itself, the lack of critical engagement with the issues raised through the interpretation represents a missed opportunity to explore wider themes.

Theme-based Interpretation

In contrast to these more traditional approaches, the core of the interpretive emphasis of theme-based interpretation surrounds the ideas, issues and actions connected with the person or people associated with the house. Crucially, the effect their lives had on contemporary society and the influence on our lives today. The interpretation is more an exploration, dealing in conflicts and controversies and in so doing, paving the way for ongoing dialogue.

Such an approach is favoured at Down House, the former home of Charles Darwin. Here, only a handful of rooms downstairs have been returned to the way they were at the time that Darwin inhabited the house, including his study, complete with specimens. These rooms provide the necessary background information on Darwin as a scientist and family man (Hems, 2006, 193) and help to contextualise and facilitate understanding of the themes presented in the rest of the museum. The upstairs of the house is dedicated to exploring Darwin’s scientific discoveries and covers the implications of the publication of the sensational On the Origin of Species, which caused a tsunami of outrage and public outpourings of all kinds, in all sectors of society at the time, the ripples of which can still be felt today. Importantly, the museum also provides space for temporary exhibitions exploring the significance of Darwin’s findings to contemporary research (Hems, 2006: 194).

(Image: Fletcher6, Creative Commons, 2012).

Taking it further – the historic property as an agent of social and political change

More recently there has been a shift towards the concept of ‘useable pasts’ where historical issues are explicitly linked to the present (Christensen, 2010). In order for this to be most effective as a learning experience, the museum visitor needs to not only be presented with the opportunity to explore the multivocality surrounding the issues presented, but also actively encouraged to critically engage with the materials (Paul, 1990: xvi).

In 1998 the International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience was formed and subsequently issued the following statement:

“We hold in common the belief that it is the obligation of historic sites to assist the public in drawing connections between the history of our site and its contemporary implications. We view stimulating dialogue on pressing social issues and promoting humanitarian and democratic values as a primary function.” (Abram, 2005, 38)

A member of this coalition is the East Side Tenement Museum in New York (Figures 1 and 2). This site, once an apartment block housing nearly 7000 working class immigrants from a wide range of countries, has been transformed into a museum exploring both the personal stories of individual immigrants, and the complex web of issues surrounding the subject of immigration, past and present (Tenement Museum, 2015). The museum operates on a guided tour system, where visitors are shown around a series of apartments reconstructed to reflect those of various families. However, it is the programme of ‘Kitchen Conversations’, operating since 2004, which made the Lower East Side Tenement Museum the first historic site in the United States to offer “ongoing public dialogue on immigration” (Abram, 2007). In these conversations, integral to the tour, visitors discuss ideas, opinions and experiences of immigrants and immigration over tea and biscuits.

(Image: Seelie, T. 2014).

The discussions are often challenging, and the facilitators are trained to maintain a neutral stance, acting only to encourage open and respectful dialogue between participants (Abram, 2007). Participants may not leave with a consensus of belief, but this is not the point. The value of such a programme lies in its ability to meld historically accurate interpretation with the provision of both the physical and the intellectual space to foster debate surrounding this often divisive issue, in a contextually relevant environment.

Also in New York, The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation was created in 2000 and is “dedicated to educating current and future generations about Gage’s work and its power to drive contemporary social change” (The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation 2009, author’s emphasis). The purpose of the museum is explicit: to continue Gage’s work in human rights and be proactive in enabling social change. In the house itself, only one room reflects the domestic life of the Gage family and the rest of the property is themed to reflect Joslyn Gage’s work. The museum includes rooms dedicated to the separation of church and state, Native American sovereignty and women’s rights. These are all issues which continue to be both of crucial importance and highly controversial today.

The museum’s drive for social change comes from the ‘Girl Ambassadors for Human Rights Programme’, run by the Foundation. This nationally recognised programme supports young women between the ages of 15 and 17 to actively build links with other girls across the world, connects with NGOs working in the field of women’s rights while also focusing on women in politics (The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation, 2014). An alumna of the programme explained the impact the experience has had on her:

“The Girl Ambassadors for Human Rights program has indubitably changed my life...While I learned a tremendous amount from girls internationally, I also learned from our own girls in Syracuse. We learned from each other, taught each other, and formed strong relationships with each other… Learning about gender inequality on a global scale impacted me tremendously; I knew I wanted to do everything I could to fight injustices in our society.” (Miller, 2009)

(Image: Daily Telegraph 2009).

These two examples illustrate museums dedicated to their role as agents of social change and represent a snapshot of the potential stored in the tangible and intangible collections of historic house museums. Using bold and imaginative approaches to embracing difficult histories, these museums drive both vital debate and social action.

Potential applications of this approach in the United Kingdom

Historic house museums in the United Kingdom represent a rich resource that could, and should, provide visitors with opportunities to engage critically with past and contemporary issues. Four possible sites are outlined below.

Properties such as Harewood House in Yorkshire and John Pinney’s town house in Bristol were built and maintained with profits derived directly from the use of slave labour (English Heritage, n.d.), yet this incredibly important part of British history is either largely ignored, or at best given minimum attention in the interpretation at these properties. This represents a significant and disturbing omission in the histories being told at these museums. There are increasing calls from heritage professionals and archaeologists for the links between the past and the present at such sites to be candidly stated and thoroughly explored through public engagement (Christensen, 2010). Embedded in the bricks, soaked into the rich textiles and ingrained in the exquisitely carved furniture of these magnificent properties are the blood, sweat and tears of slaves. In these surroundings lies an exceptional opportunity not only to explore the past, but also to confront and examine the faces of modern-day slavery and indentured working practices, both in the UK and across the world.

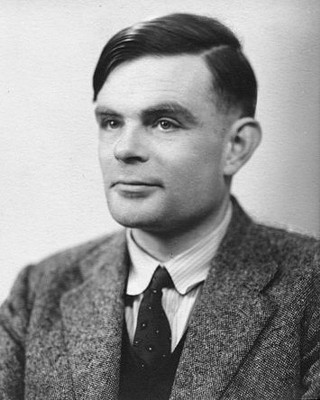

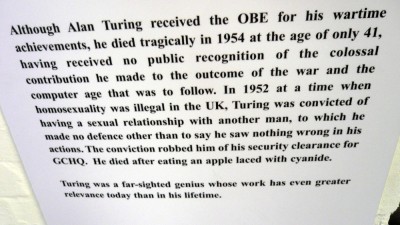

An opportunity to explore issues surrounding sexuality and discrimination is presented at Bletchley Park, the location of secret codebreaking activity during World War 2 and now a museum which includes information on Alan Turing (Figures 3 and 4). Turing was a genius mathematician and is now recognised as the father of computer science and artificial intelligence. His actions in developing a computer to crack the Nazi encryption device, the Enigma machine, saved countless lives, but he was later convicted of ‘gross indecency’ for homosexual acts which, at that time, were illegal. He chose chemical castration over imprisonment and two years later he committed suicide. Turing was granted a posthumous royal pardon in 2013 but another estimated 50,000 homosexuals, also charged under the same law, remain criminals (BBC, 2013). Bletchley Park, once the site of an intellectual battle to preserve Britain’s freedom from outside oppression, represents a unique environment in which to open and facilitate dialogue around modern matters of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights.

Using the Lower East Side Tenement Museum as a model, a similar programme could be implemented at the Birmingham Back-to-Backs museum (Figure 5), with facilitated discussions centering on class issues in contemporary Britain. As one of a minority of vernacular house museums dedicated to telling the stories of the working classes, the back-to-backs represent an exceptional opportunity to explore such a complex and multi-layered issue which resonates so strongly through life in Britain today. With a thoughtful and dedicated marketing and outreach programme, visitors from lower socio-economic groups within the United Kingdom—traditionally under-represented in heritage audiences—would perhaps be more likely to visit and take part.

Some factors to consider

Transforming a historic house museum from a place that merely interprets history to one that also promotes contemporary social change will require in-depth research and careful planning. A fundamental decision needs to be taken on what kind of approach or combination of approaches will be utilised. These could range from the addition of a layer of interpretation to existing resources aimed at encouraging critical engagement and reflection, through to organised sessions of discussion between visitors or developing a programme aimed at engaging a specific demographic group. The museum will also need to decide whether visitors can choose to engage or whether engagement forms an integral part of every visit. Some of these decisions may come down to practicalities such as available space and of course, funding. The need for committed and well trained staff is crucial to the success of any programme where controversial and challenging themes are explored or public dialogue is encouraged. Well trained staff are also more likely to be or become supportive of the programme as they feel secure in their capabilities to deal with potentially difficult situations that may arise.

Change can be a difficult process, especially if the museum initiates a radical alteration to what they normally offer to the public. This can lead to disparity between the visiting public’s expectations and their experiences, with the potential to impact negatively on the site. Strong leadership and effective communication is a key factor in preventing this and seeking advice from those museums that have been successful in running such programmes is of fundamental importance. Similarly, advice should be sought to enable a balance to be struck between exploring these sensitive and often emotionally engaging issues and the potential to cause empathy fatigue in visitors. The tone of the interpretation or programme can help achieve this balance. The neutrality of the facilitating staff of the East Side Tenement Museum is no doubt a key factor in the positive reception the programme has received from visitors. This is not the traditional authoritative voice of the museum presenting facts to be taken as read, but a historic site, with a relevant history, providing space and resources for debate and discussion on important issues.

Conclusion

This essay has argued that, due to their historical significance and unique ability to connect with visitors as places of dwelling, historic house museums should, where appropriate, introduce interpretation or programmes aimed specifically at linking their pasts with contemporary experiences. This will often involve groups who are routinely marginalised or discriminated against, both in society in general and explicitly within the heritage sector. This includes, but is not limited to, women, immigrants, members of the LGBT community, lower socio-economic groups and indigenous peoples. Implementing such an approach would represent a fundamental shift from traditional exhibition content and delivery and challenge the hegemony of the AHD by introducing more dissonant heritage.

The United Kingdom has a long, complicated and often unsettling history, much of which can be explored in historic house museums and their stories. Contemporary society presents challenges that are inextricably linked to our past and these narratives. These sites have an obligation to operate as agents of social change by actively encouraging and facilitating open and informed critical engagement around the contemporary manifestations of the historical issues they present.

Bibliography

- Abram, R. (2005). History is as history does. In R. Janes, and G. Conaty (Eds.). Looking Reality in the Eye: Museums and Social Responsibility. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, pp. 19 - 42.

- Abram, R. (2007). Kitchen Conversations: Democracy in Action at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. The Public Historian, 29(1).

- BBC. (2013). Royal pardon for codebreaker Alan Turing. [Online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-25495315 [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- Benton, T. and Watson, N. (2010). Museum practice and heritage. In S. West. (Ed.). Understanding Heritage in Practice. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 127 - 165.

- Christensen, K. (2010). Ideas versus things: the balancing act of interpreting historic house museums. [Online]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.541068 [Accessed 10 February 2015].

- Donnelly, J. F. (2002). Introduction. In J.F. Donnelly (Ed.). Interpreting Historic House Museums. Oxford: AltaMira Press, pp. 1 -17.

- English Heritage. (n.d.). The Slave Trade and Plantation Wealth. [Online]. Available at: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/discover/people-and-places/the-slave... [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- Hems, A. (2006). Thinking about interpretation: Changing perspectives at English Heritage. In A. Hems and M. Blockley, (Eds.). Heritage Interpretation. London: Routledge, pp. 189 - 200.

- Hughes, H. (2008). Your monument … temple, my castle, my home: a theory for historic interiors research and conservation. [Online]. Available at: http://www.helenhughes-hirc.com/pdf/new_dehli_helen_hughes.pdf [Accessed 4 December 2014].

- Miller, L. (2009). Reflections from Girl Ambassador Alumni. [Online]. Available at: http://www.matildajoslyngage.org/about-the-center/girlambassadorsforhuma... [Accessed 10 March 2015].

- National Trust. (n.d.). Birmingham Back-to-Backs. [Online]. Available at: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/birmingham-back-to-backs/ [Accessed 6 March 2015].

- Oram, A. (2011). Going on an outing: the historic house and queer public history. Rethinking History, 15(2).

- Paul, R. (1990). Critical Thinking. What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world. California: Sonoma State University.

- Sandell, R. (2007). Museums, Prejudice and the Reframing of Difference. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of Heritage. Oxon: Routledge.

- Tenement Museum. (2015). A Landmark Building, a Groundbreaking Museum. [Online]. Available at: http://www.tenement.org/about.html [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation. (2009). Mission and History. [Online]. Available at: http://www.matildajoslyngage.org/about-the-center/mission-and-history/ [Accessed 10 March 2014].

- The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation. (2014). Girl Ambassadors for Human Rights. [Online]. Available at:

http://www.matildajoslyngage.org/about-the-center/girlambassadorsforhuma... [Accessed 10 March 2014]. - Tilden, R. (2007). Interpreting our Heritage. In R. Craig (Ed.). North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Young, L. (2007). Is there a Museum in the house? Historic houses as a species of Museum. [Online]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09647770701264952. [Accessed 15 February 2015].

Image Bibliography.

- Figure 1: Creative Commons. (2013). Exterior of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. [Online]. Available at: http://iyftc1oqf704bytwz45ub151.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploa... [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- Figure 2: Seelie, T. (2014). Cramped quarters of a tenement. [Online]. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2886995/Immigrant-lives-frozen-t... [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- Figure 3: Daily Telegraph. (2009). Alan Turing. [Online]. Available at: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/01373/Alan-Turing_1373122b.jpg [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- Figure 4: Doctorow, C. (2008) Turing’s Suicide Notice. [Online]. Available at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/doctorow/2686877562/ [Accessed 9 March 2015].

- Figure 5: Creative Commons. (2014). Birmingham Back to Backs exterior. [Online]. Available at:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/Birmingham_Back... [Accessed 5 March 2015].