In an incident dubbed by Tatiana Proskouriakoff as the ‘arrival of the strangers’ and known among Mesoamericanists as the entrada, Sihyaj K’ahk’ established a new dynasty at the Classic Maya site of Tikal which spanned at least 300 years and was responsible for the zenith of the Tikal’s influence in Mexico (Martin and Grube 2008, 42). The historical episode marks a crucial yet uncertain juncture in the formation of Maya civilisation and interaction between it and the lesser-known Central Mexican metropolis of Teotihuacán (Proskouriakoff 1984, 164). However, ambiguity in the retrospective epigraphic record and conflicting archaeological data has led to conflicting explanations of the entrada event. An epigraphic perspective attributes the brief florescence of Teotihuacán iconography and material culture to a foreign military incursion led by the obscure figure Sihyaj K’ahk’, who established the influence of the City of the GodsTeotihuacán throughout the Maya Lowlands (Coggins 1975, 8; Stuart 2000, 465). A revisionist viewpoint utilises empirical archaeological data to suggest that Maya dynasties emulated Central Mexican styles for political advantages, with the expansionist agenda of Early Classic Tikal being achieved through the adoption of foreign iconography and military technology (Braswell 2003b, 83). Both standpoints show a tendency to overlook changes outside the Maya Region, and are fundamentally limited by their near exclusive use of either epigraphic or archaeological evidence to support current explanations of the entrada.

By adopting a wider scope and using multiple lines of evidence, this article aims to present an alternative hypothesis for the ‘arrival of the strangers’ in AD 378 (Proskouriakoff 1993, 43). The sudden appearance of Sihyaj K’ahk’ at Tikal was likely the result of a series of causally linked socio-political developments at the Teotihuacán (Cowgill 1993a, 116). Exiled agents of the Feathered Serpent seem to have used military force to assert their newfound independence as dynasts of Tikal, a city on the periphery of the Teotihuacán hegemony. Having witnessed the success of these foreigners, Lowland Maya elites incorporated Central Mexican martial strategies and iconography into regional traditions for their own political gain, most dramatically during the conquest of Copán by Yax K’uk’ Mo’ in AD 426 (Fash and Sharer 1991, 180).

As a historical episode, the core primary evidence for the entrada of AD 378 is a group of five retrospective stelae from the Early Classic Maya sites Tikal and Uaxactún (Stuart 2000, 477; Figures 1 and 2).

|

Stela |

Location |

Date |

Presiding k'uhul ajaw Ruler |

Brief Description |

|

4 |

Tikal |

396 |

Yax Nuun Ahiin I |

Yax Nuun Ahiin I, the son of “Spearthrower Owl”, was installed as a y-ajaw “vassal” by Sihyaj K’ahk’ and then celebrated the k’atun ending date of 8.18.0.0.0. |

|

5 |

Uaxactún |

396 |

Sihyaj K’ahk’ ? |

A fragmentary text that describes the hul "arrival" 378 event of the Sihyaj H'ahk' to Uaxactún |

|

Marcador |

Tikal |

416 |

Sihyaj Chan K’awiil II |

A long and complex text that mentions the accession of a unknown figure named “Spearthrower Owl” over an undeciphered location in 374, the hul “arrival” 378 event of Sihyaj K’ahk’ to Tikal, and the death of “Spearthrower Owl” in 439. |

|

31 |

Tikal |

445 |

Sihyaj Chan K’awiil II |

A stela giving a partial history from the entrada to 445. The inscription describes the journey of Sihyaj K’ahk’ from an unknown starting point, stating suts-uy “it ended” followed by an unknown toponym and ok “foot, leg.” It also cryptically reveals that the ruler of Tikal Chak Tok Ich’aak I och-ha “entered the water” on the date of the entrada, a common expression for death among the Classic Maya. |

|

22 |

Uaxactún |

504 |

Ruler A-22 |

Ruler A-22 celebrated the six k’atun anniversary of the Hul “arrival” 378 event of Sihyaj K’ahk’ to Uaxactún, 9.3.0.0.0. |

Figure 1: The five primary stelae with Gregorian dates, ruling k’uhul ajaw and brief descriptions. While the inscriptions clearly indicate that Sihyaj K’ahk’ both lived at Uaxactún and commissioned Stela 5, it remains only implied that he was the presiding k’uhul ajaw. The Maya name of Ruler A-22 remains undeciphered and is temporarily named after his burial number by archaeologists excavating Uaxactún (Figure: author’s own, based on Stuart 2000, 477-479; Martin 2003, 12-13; Martin and Grube 2008, 30-35).

| (i) | Sihyaj K’ahk’ arrived from an undisclosed location in the west on 16th January AD 378, 11 Eb 15 Mak 8.17.1.4.12, traditionally assumed to have been from Teotihuacán. |

| (ii) | Chak Tok Ich’aak I suddenly died and Yax Nuun Ahiin I, the son of an ambiguous person named “Spearthrower Owl”, was invested as the k’uhul ajaw of Tikal by Sihyaj K’ahk’. |

| (iii) | On the same day, Sihyaj K’ahk’ also ventured to Uaxactún where he exerted newfound authority over the long-standing rival of Tikal. |

Figure 2: A generally accepted basic summary of the major events of the entrada in chronological order (Figure: Author’s own, based on Coe 2011, 102; Schele and Freidel 1990, 163).

However, the lack of impartiality by original Maya authors and limited understanding among modern scholars has led to subjectivity in epigraphic explanations of the entrada. For example, the Marcador proclaims that Sihyaj K’ahk’ arrived in the company of Chan Ajaw K’uh, “Sky Lord God”, and Ochk’in Waxaklajuun Ub’aah Kan, “Western Eighteen Snake Heads” (Estrada-Belli et al. 2009, 243). K’uhul ajaw was a universal title for Classic rulers and may refer to a local allied Maya lord, yet the name “Western Eighteen Snake Heads” bears no resemblance to any known royal titles. The identities of many characters mentioned in the epigraphic record remain ambiguous and do not necessarily reflect historical figures. Without emic clarity of the inscriptions, perspectives primarily constructed using the epigraphic record cannot easily hope to achieve detailed understandings of the entrada at Tikal and include significant speculation in proposed narratives.

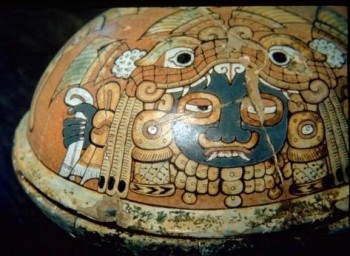

Evidence beyond the epigraphic record for political upheaval in the Petén draws from a brief adoption of Central Mexican styles and martial iconography by the new ruling elite of Tikal. Burial PTP-010, the tomb of Yax Nuun Ahiin I, was discovered beneath Temple 5D-34 of the North Acropolis (O’Neil 2009, 124). The funerary ceramic assemblage included a variety of Central Mexican elements, such as a balanza black cylinder tripod bearing the inscription “the drinking vessel of the son of Spearthrower Owl”; a thin orange lidded vessel painted with a decoration of the Feathered Serpent deity; and a fine creamy paste effigy covered in painted stucco, typical of high-status pottery decoration at Teotihuacán (Figure 3; Harrison 1999, 86-87; Orellana et al. 2008, 70).

Further foreign influence on local ceramic production is evident across eight of sixteen contemporary problematic deposits relatively dated to Manik 3A, which contained ceramics in Teotihuacán candelero styles and decorated using Central Mexican “coffee bean” appliqués (Ponce de León 2003, 182-183).

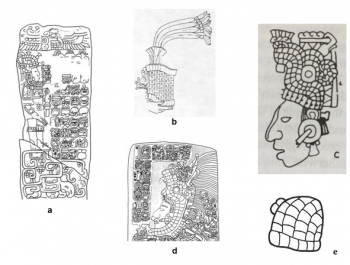

Both Yax Nuun Ahiin I and Sihyaj Chan K’awiil II also borrowed Central Mexican imagery for their portraits, rather than relying on Pre-classic Maya artistic cannons, to support the newfound authority of the k’uhul ajawob (Miller and O’Neil 2014, 121). Stelae 31 and 32 associated Yax Nuun Ahiin I with Tlaloc using characteristic goggle-eyes, common in murals throughout the apartment compounds of Teotihuacán, as well as depicting new instruments of warfare previously unseen in the Maya Area such as rectangular shields, atlatls and accompanying darts, and shell platelet helmets (Berrin 1993, 78; Slater 2011, 377). Contemporary monumental efforts focused on domestic dwellings in Group 6C-XVI and Structures 5C and 5D within the civic-ceremonial heart of Tikal, incorporating the foreign talud-tablero and stairway balustrade architectural forms into the renovations of key buildings dating to the previous dynasty (Laporte 2003, 201-204; Borowicz 2003, 217). Although neither archaeological nor iconographic approaches can adequately reveal details of historical actors, they remain essential in order to contextualise a partial, ambiguous, and self-serving epigraphic record, and testify to dramatic culture change among Early Classic elites at Tikal.

All interpretations of the entrada in AD 378 are inevitably entangled with broader discussions of Teotihuacán expansionism. Traditionally, the presence of Teotihuacán material culture across a host of Classic sites within prosperous regions, such as Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Central Mexico, were explained using economic models of imperialism which emphasised colonisation and resource appropriation (Ball 1974, 2; Coggins 1993, 150). Thus Alfred Kidder attributed Esperanza phase Thin Orange ceramics and talud-tablero architectural features of Mounds A and B at the Maya Highland site of Kaminaljuyú as the by-product of Teotihuacán interest in local obsidian sources (Kidder 1945, 74; Kidder 1961, 561). However, a revisionist archaeological perspective attributes the relatively low material presence of Central Mexican artefacts and architectural styles at Classic Maya sites such as Altun Ha, Escuintla, and Nakum to cultural exchange between various Mesoamerican groups (Braswell 2003a, 4). Talud-tablero architectural forms imply that foreign styles were adapted by local elites, for example Mounds A and B at Kaminaljuyú have a height ratio of 1:1 talud-tablero in comparison with the Teotihuacán range of 1:1.6-1:2.5 (Laporte 2003, 205; Cowgill 2003, 321). Empirical data has revealed that individuals interred with foreign goods were Maya rather than foreign elites: 87Sr/86Sr ratios from the teeth of Yax Nuun Ayiin suggest that the son of “Spearthrower Owl” was raised at Tikal, rather than at a Central Mexican site (Wright 2005, 97). Teotihuacán material culture in the Maya Area is interpreted as the result of a Pan-Mesoamerican exchange of goods, in which Maya elites adapted foreign styles to suit local tastes and political agendas.

An alternative hypothesis can be offered in which exiled agents capitalised on pre-existing trading and diplomatic relations between Teotihuacán and the Maya Area to fulfill their own interests. Foreign Barrios at Teotihuacán show that the city was a major trading player within the Mesoamerican world system (Blanton et al. 1992, 673). The Zapotec Barrio imported exotic resources such as lime, mica, and cochineal from Monte Albán, while potentially Maya occupants of the Merchants’ Barrio obtained jade, flint, amber, and ceramics from Belize (Manzanilla 2018, 94; Gómez Chávez 2018, 104). Diplomatic efforts by the state are visible in Burial 5, a primary interment consisting of three adult males at the centre of stage six of the Moon Pyramid relatively dated to AD 350 (Sugiyama and López Luján 2007, 132). Strontium and oxygen isotopes enter the human body through diet and are fixed into biogenic enamel layers, therefore can be used to gauge an individual’s movement between varying geological regions where food and water were sourced (White et al. 2007, 159). Analysis of first premolars yielded 87Sr/86Sr ratios very similar to values within the Motagua Valley, suggesting that all three males spent their early childhood within the Maya Area; only individual 5A had a bone δ18 O value that would indicate he had resided at Teotihuacán for a significant length of time (White et al. 2007, 168). The substantial quantity of accompanying jadeite and central position within the Moon Pyramid denote an honorific Maya-style interment of k’uhul ajawob, particularly given that no other clear burial of elites in any public context at Teotihuacán have yet been discovered. In sharp contrast with previous interments of executed war captives (Sugiyama and Cabrera Castro 2007, 115), both the “lotus” body positions, typical of seated Maya elites depicted on ceramics, and remaining fibers of a woven mat, symbolic of rulership (Spence and Pereira 2007, 152), suggest that the persons within Burial 5 were high-status foreigners who were granted an unprecedented elaborate funeral by the Teotihuacán state. As the only known source of jadeite in the Mesoamerican macro-regional exchange network was within the Motagua Valley (Houston 2014, 94), Burial 5 perhaps marked a diplomatic effort to secure friendly relations with local k’uhul ajawob in order to access to this prized and exotic resource. Previous interactions with the Maya Area as late as approximately 30 years prior to the entrada at Tikal apparently favoured a policy of trade and diplomacy, rather than far-reaching military incursions.

Approximately contemporaneous with Burial 5 was a rejection of the cult of the Feathered Serpent and the militaristic ideals that it had represented (Cowgill 1992, 108; Toby-Evans and Nichols 2016, 26). The façade of the temple was deliberately incinerated and a new adosada platform, that masked the previous structure, was constructed in an event relatively dated to AD 350 using ceramic seriation of Late Tlamimilolpa phase sherds (Cowgill 2015, 146). Surviving fibers indicate that most of the 132 complete bodies interred within the Feathered Serpent Pyramid were bound and gagged before being entombed with various obsidian blades and pyrite back disks diagnostic of captured warriors (Gazzola et al. 2016, 118; Carballo 2007, 179). The execution of at least 200 captives with at least four different 87Sr/86Sr ratios (White et al. 2002, 217) in a roughly 150-year time frame clearly shows that the temple was sanctuary to a militaristic faction, further supported by iconographic parallels between sculptures on its external façade and depictions of Xiuhcoatl, a Post-classic Central Mexican war deity (Taube 1992, 53). The denunciation of an aggressive militaristic cult must have had socio-political ramifications for its ostracised adherents, perhaps further antagonised by privileges granted to the Maya individuals within Burial 5. The entrada might have been a consequence of factionalism at Teotihuacán that culminated with independent agents using their martial proficiency to assert their authority within the Maya Area, beyond the reach of political adversaries in the City of the Gods.

Specific evidence connects the Feathered Serpent with the entrada at Tikal, for example Teotihuacán images associated with the cult, such as the shell platelet headdress, replaced Pre-classic Maya artistic canons that had previously emphasised themes of ancestry (Figure 4; Estrada-Belli 2011, 122).

The titles of Chan Ajaw K’uh and Ochk’in Waxaklajuun Ub’aah Kan mentioned on Stela 31 are possibly honorifics of the Feathered Serpent deity. Attention to repeated, ritually significant numbers in Feathered Serpent interments, such as 18 bodies in Graves 190, 17, 153, and 203, shows the significance of the tonalpohualli and other calendrical counts in Teotihuacán cosmology (Sugiyama 2005, 97; Spence and Pereira 2007, 151). Given its western direction from the Maya Area, calendrically prominent number, and the characteristic serpent heads that defined the façade of the monument, “Western Eighteen Snake Heads” might specifically refer to the Feathered Serpent Pyramid rather than a human actor. The Feathered Serpent deity developed into Quetzalcoatl, the Post-classic Central Mexican deity of wind and sky (Anonymous, Codex Borgia, Plate 36; Sugiyama 2005, 222). “Sky Lord God” matches Post-classic descriptions of Quetzalcoatl, indicating that Sihyaj K’ahk’ likely arrived at Tikal accompanied by the ousted Feathered Serpent cult.

The enduring impact of the entrada at Tikal upon the Maya Area was essentially bellicose. Classic Maya elites appropriated martial iconography and equipment familiar from the Feathered Serpent Pyramid for regional political gain (Grube and Schele 1994, 10). The lack of spondylus shell platelets in Maya elite burials prior to the Early Classic Period suggests that the Maya adopted this piece of military equipment after the entrada (Figure 5; Taube 2000, 282).

A conquest of Copán by Yax K’uk’ Mo’ in AD 426 shows Maya emulation of Teotihuacán martial strategies, with the previous dynasty disappearing from the epigraphic record, their monuments broken and buried (Manahan and Canuto 2009, 534). Dedicated in AD 776, Altar Q retrospectively portrayed the founder as a Teotihuacán warrior equipped with a Tlaloc shield and eye-goggles (Fash 2001, 89). Epigraphic texts similarly frame the foundation of a new ruling dynasty as a hul “arrival” event, for instance a commemorative step dating to AD 429 proclaims Yax K’uk’ Mo’ as “Lord of the West” and enigmatically mentions Sihyaj K’ahk’ as a potential sponsor of his military venture (Fash and Fash 2000, 446). Yax K’uk’ Mo’ was interred within the Hunal structure constructed in a talud-tablero style, and an 87Sr/86Sr ratio from his first molar matched approximate values of the Miocene limestone of the Petén, further suggesting significant contact with Tikal prior to his conquest of Copán (Sharer et al. 1999, 4; Douglas-Prince et al. 2008, 174). A Late Classic refounding of the city of Seibal by the Maya outsider Ah Bolon Wat’ul Chatel in AD 830 was also presented as a hul “arrival” event on Stela 11, rather than using either the ?-Ya “Star War” or Took’ Pakal “Flint Shield” glyphic conventions that indicate warfare without explicit dynastic usurpation (Schele and Mathews 1999, 183). Classic Maya elites clearly identified dynastic founding through conquest with Teotihuacán militarism. The entrada at Tikal acted as a catalyst for Maya elites adopting martial innovations and strategies, most likely due to the impression that Sihyaj K’ahk’ left on the area through his own military exploits in AD 378.

Neither epigraphic nor archaeological interpretations of the entrada adequately explain the ‘arrival of the strangers’ at Tikal (Proskouriakoff 1993, 43). Approaches that rely upon epigraphic texts are currently hindered by a lack of emic understanding. Perspectives utilising archeological data fail to account for contemporary socio-political change at Teotihuacán. This article has aimed to present an alternative hypothesis, in which the destruction of the cult sanctuary of the Feathered Serpent and privileges granted to foreign Maya k’uhul ajawob causally provoked independent Teotihuacán agents to assert their authority over distant Tikal. The enduring influence of this military venture was the adaptation of Teotihuacán technologies and strategies by Classic Maya elites to fulfill their own warlike interests, most explicitly during the conquest of Copán in AD 426. Perhaps as new evidence emerges, this hypothesis can be more rigorously tested and aspects contributing to the controversy of the entrada at Tikal better clarified.