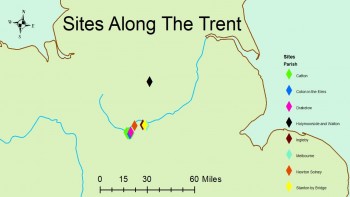

The 9th century in England was a particularly turbulent period of its long history which saw successive Scandinavian raids evolve from hit and run incursions, to an organised invasion with the objective of acquiring Anglo-Saxon land for settlement (Hadley et al. 2016, 24). This article builds on the dissertation research of Ben Hume which discovered new artefactual evidence of the Viking Great Army in Derbyshire through use of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) database (Hume, 2020). Through this research, it became apparent that the river Trent was an extremely significant artery into the heart of the kingdom of Mercia. Seven sites (Figure 1) located along its course provided artefactual evidence which bore the archaeological ‘signature’ of the Viking Great Army as identified by Hadley and Richards in their 2018 article (Hadley and Richards 2018). Previously studied sites such as Heath Wood cremation cemetery (Richards et al. 2004), Foremark (Jarman: Britain’s Viking Graveyard, 2019) and most famously, Repton (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle 2001) are also located along the course of the Trent which suggests that the river itself is the key to recognising interconnectivity between sites bearing the archaeological signature of the Great Army.

The Use of LIDAR in Derbyshire

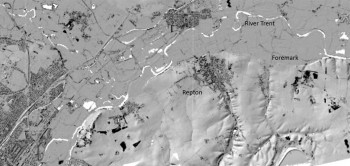

First of all, when analysing sites along the course of the Trent, it is important to acknowledge that its course will have changed over time as it is noted for its high channel mobility throughout the Holocene (Stein et al. 2017, 114). However, LIDAR surveys provide an extremely useful insight into the palaeochannels of the river and evidence how, despite its mobility, the course has not altered significantly enough to invalidate the analysis as the sites are still located close to the river. Figure 2 clearly demonstrates the course of the Trent and also provides potential for targeted archaeological investigation in the palaeochannels. Waterlogged, anaerobic conditions are favourable for the preservation of dateable organic materials such as wood, which can then be investigated through radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology (Carver 2009, 269) in order to corroborate typological dating of PAS finds.

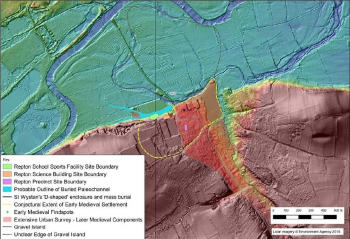

As well as survey data from the Lidarfinder website, the Environment Agency (Figure 3) also provides data of the area around Repton as utilised by Davies in his 2019 article (Davies 2019) which investigated the landscape surrounding the site. Through this analysis, it was suggested that a former palaeochannel of the Trent flowed eastwards into a channel to the north of St Wystan’s church which makes up part of the Repton fortifications (Davies, 2019, 6). This channel would have been filled seasonally rather than accessible all year round, suggesting that there are different site types related to the activities of the Great Army, as the launching of ships was a priority for attack and defence. Furthermore, the size of the defensive church enclosure has also been called into question as 0.4 hectares would have been too small to accommodate the Army and its ships (Jarman, 2019), suggesting that Repton may have been a landing site allowing for further expansion along the Trent. The seasonal nature of the palaeochannel therefore parallels with other ‘island’ sites such as Torksey in Lincolnshire which is now well known as a winter camp for the Viking Great Army and was situated within a multichannel fluvial system on the Trent (Hadley et al. 2016, 32).

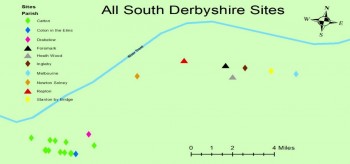

After considering the LIDAR data and also the artefactual evidence from the PAS, it is possible to demonstrate a clear correlation between the location of the sites and the course of the river Trent (Figure 4), confirming it as an essential highway into the heart of Mercia; Scandinavian settlers relied heavily on the movement of people and supplies on their ships which was vital for overwintering in a hostile environment (Carroll et al. 2014, 15).

Viewsheds and Semiotic Analysis

As well as examining the landscape and spatial distribution of sites along the Trent, it is also possible to use viewsheds through digital elevation models in order to examine intervisibility between sites. Research conducted by Gustavsen (2000) has suggested that both Repton and Foremark would have been visible from the ridgeline on which the barrows of Heath Wood are located. Heath Wood itself is a unique site in Britain as it is the location of the only known Scandinavian pagan cremation cemetery and has been dated to the late 9th century, suggesting it was the war cemetery used by the Viking Great Army (Richards et al. 2004, 99). A cemetery overlooking the settlement it serves is not unique to Repton and is paralleled at the site of Lindholm Høje in Denmark where the cemetery overlooks the Limfjord (Johansen 1996, 7). This implies that there is a spiritual rationale behind this as conducting cremations on the top of the ridge would have been impractical. In order to analyse this relationship, a useful source is The Prose Edda which, despite being written a few centuries later, is the primary source for information regarding Norse cosmology (Byock 2005). The Prose Edda states that Valhalla was where many battle-slain warriors found their afterlife. This is significant as Valhalla is located within Asgard, the realm of the gods, and is found at the top of the world tree named Yggdrasil which overlooks the rest of the realms (Gylfaginning Saga, 39). When analysed semiotically, the juxtaposition of the specifically pagan Heath Wood and the Christianised Repton suggests that the former is indexical of Valhalla (the realm of the dead) and the latter, indexical of Midgard (the realm of the living). Spatial analysis of sites in Derbyshire is therefore extremely useful for producing interpretations and when paralleled with written sources, theories can be furthered as many aspects of religion and belief are archaeologically invisible.

Conclusions

When considering the movements of an army which was predominantly used to moving by sea or river, it is clear why the Trent was such a significant artery into the heart of the kingdom of Mercia. Moreover, it is important to consider these individual sites in their broader context and how they related to one another instead of simply in isolation. LIDAR surveys coupled with artefact distribution presents a compelling case to suggest that Viking Great Army sites were intentionally located along the Trent to provide access to ships. Furthermore, semiotic analysis suggests a ritualised rationale based on the intervisibility of Repton and the barrows of Heath Wood which would have stood as a spiritual beacon on the ridgeline above. Further research into the wider context of the river would be beneficial to test whether the site location pattern is also repeated outside of Derbyshire.

![Figure 1 ref: A, Lancaster. (nd.) Early Medieval Wales. Available at: viking-5-wales-vikings-on-the-coast.jpg [accessed 17/02]](https://theposthole.org/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/article_thumb/public/articles/506/Figure%201%20%281%29.jpg?itok=22FvdRE7)