Today, modern humans seem to have lost an integral factor which formerly influenced sociality. In the primate and ethnographic records, we find that the availability of certain seasonal resources opens up opportunities for aggregations and can greatly influence proclivities towards both social tolerance and hierarchies (Hare and Wrangham 2017). Given the influence that the environment can have upon hunter-gatherer and primate sociality, it would be interesting to explore the role the environment played in sociality during the Palaeolithic.

With the use of the ethnographic, primate and prehistoric record, the role of seasonal aggregation in opening up social opportunities will be highlighted. Further, the impact the environment can have upon how communities organize themselves will be assessed. It is the aim of this paper to illustrate that the environment not only impacted a networks’ social dynamics, but with the fluctuating availability of resources, it offered social flexibility.

Bringing the group together

The opening up of seasonal resource availability likely played a role in establishing inter-group networks and opening opportunities for socialization. It is perhaps all too easy to forget about seasonal movement since we ourselves rely heavily upon resource concentrated spots within our own modern landscape. However, when looking at the ethnographic record it is surprising to see how frequently hunter-gatherers must move in order to obtain resources that are seasonally available. For example the Ju/’hoansi of the Kalahari occupy ripened summer food spots between 3 weeks to 3 months in the rainy season, then move to seasonal pans rich with berries and mongongo, and then move to more permanent waterholes in the winter (Lee 2013, 32). Of significance is the fact that seasonal change provides some degree of structure to social gatherings.

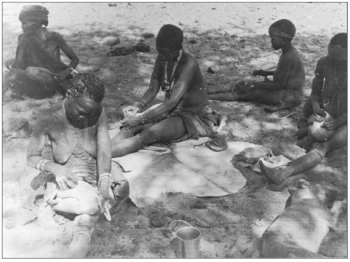

During the winter period, prior to over depletion of the resources, the locale surrounding the permanent pan offers the Ju/’hoan heat with its nearby firewood and different roots and bulbs (Lee 2013, 32). With this large groups can meet friends from across the landscape, form new friendships, through hxaro trading and dance without over depleting resources (Lee 2013, 134). Like many hunter-gatherer groups, the Ju/’hoansi function in a fission-fusion society in which the main group of 20-50 people following aggregation in the dry season will subdivide into smaller groups during the rainy season (Lee 2013, 127). This is a similar behaviour to chimpanzees of the Gombe forest who aggregate into large parties when ripe fruit is plentiful and potential for competition is low (Gilby et al. 2006, 170; Goodall 1986, 155).

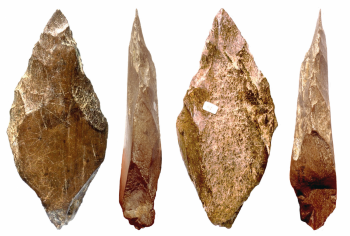

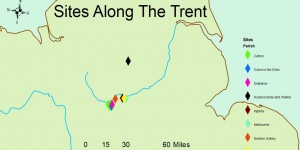

Our understanding of seasonal movement is obviously more detailed in the ethnographic and primate record than the prehistoric. However, glimpses into such a lifestyle can be obtained by the potential use of the sites of Pavlov I and Dolní Věstonice I for seasonal aggregation spots for Gravettian modern human groups during a period when the glaciation process created cold and dry climates in northerly latitudes (Maier and Zimmermann 2017, 574; Djindjian 2015, 1). Here sites are suggested to have offered groups advantageous low altitude spots within the river valleys overlooking migrating megafauna (Svoboda et al. 2005, 210). Significantly in bringing together communities, the elaboration of complex symbolic material culture and performances of creative burials could occur. For example, at Dolní Věstonice in Moravia, burials consisted of elaborate headdresses, whilst furs and marine shells were exchanged on central Russian plain sites (Soffer 1985, 442-443). Again such complex social behaviours has also been afforded to modern hunter-gatherers such as the Mbendjele of the congo who, following a sporadic elephant hunt, will call distant groups together to feast and perform spirit plays which also require trading, particularly of the right to perform the play (Lewis 2015, 6). In this way the emergence of rare resources within the landscape is important to sociality for both primates and modern humans. Ultimately, the collation of an abundance of resources provides the venue for aggregation in which complex social interaction and creativity can occur. It is possible to hypothesize that such aggregations had early origins during the lower Palaeolithic when early humans, potentially H. erectus/ergaster, processed carcasses of megafauna like proboscideans in East Africa. Whilst highly speculative, intriguing non-functional Acheulean handaxes made of elephant have been located suggestive of some sort of socio-cultural membership or elaboration, perhaps resulting from large groups aggregating to share this large, hard to obtain prey (Barkai 2019, 163). The value of the environment is perhaps being overemphasized in this paper, it does nevertheless unlock opportunities for extending social connectivity and productive elaborations with otherwise distant social groups. Thus far, the fluidity in the behavioural changes with ebbs and flows of the availability of resources have been highlighted. With different resources to exploit and climatic challenges to face, it is worth investigating the way social organization was influenced.

Resource availability and its influence on friendliness and social order

Social orders and intra-group sociality were likely highly intertwined with the environmental pressures and exploitation opportunities. In the primate record this is especially notable in the social behavioural and environmental differences between chimpanzees and bonobos. Whilst bonobos and chimpanzees both consume leaves of terrestrial herbs as fallback foods, chimpanzees must compete for this with gorillas whilst bonobos can forage in peaceful parties (Hare and Wrangham 2017, 159). There are thus more selection pressures upon chimpanzees for hierarchical, competitive cognitive adaptations, whilst bonobos show a higher propensity for social tolerance and reduced male-male competition (Hare and Wrangham 2017; Tokuyama et al. 2019, 11; Wobber et al. 2010). Figure 3 provides an illustrative example of the extent to which bonobos tolerate the presence of others whilst feeding.

Similar environmental concerns and opportunities also likely have had some impact upon the social order of Homo of the Upper and Middle Palaeolithic. As noted previously, the glacial processes of the Last Glacial Maximum created a bitter climate for most Gravettian sites, which seemed to occupy regions with winter temperatures below 0 degrees Celsius (Davies 2003, 140). Interestingly, alongside these harsh conditions, the Gravettian humans seem to have adopted ‘delayed-return’ lifestyles and economies. This economic system is used by some modern hunter-gatherers for organizing their subsistence economies, and involves the usage of storage devices, mass-production facilities and dwellings (Woodburn 1982, 432-433). Against this deteriorating climatic backdrop, groups constructed dwellings and storage facilities in Slovakia, Moravia and Russia (Pettitt 2018, 140; Pryor 2008, 170-1). Potentially there were social organizational implications to this. Two case studies illustrate the dramatic effect resource dispersal can have upon social organization and social dynamics. The Twana of the Coast Salish, an indigenous group from the Pacific Northwest Coast, experience greater pressures at work during the productive salmon season and thus adopt a delayed return system and become more territorial and hierarchical (Rowley-Conwy and Piper 2016, 4-5). In contrast, despite possessing storage facilities, the Netsilik of Pelly Bay, another indigenous group reliant on fishing in the Canadian arctic, rely on unpredictable and scattered resources and thus are neither hierarchical nor territorial (Rowley-Conwy and Piper 2016, 4-5). With this the role the environment can have in influencing social dynamics and organization is notable. As noted previously the seasonal movements contribute some sort of fluidity to sociality. Indeed, the Eskimos exhibit such “social plasticity” as they are communalistic in the winter, and territorial in the summer (Wengrow and Graeber 2015, 597, Mauss and Beuchat 1979, cited in Wengrow and Graeber 2015, 606-7). It is therefore possible that early humans’ social order and group dynamics was not only affected greatly by the seasons but that it could have brought about social behavioural change.

Conclusion

Overall, the environment seems to have considerable influence over sociality of not only extant mammalian groups but also likely of prehistoric human groups. Whilst it unlocks opportunities for social connectivity amongst inter- and intra-group by allowing the meeting of distant and new groups, it can also deter socialization and trigger territorial and hierarchical tendencies. Whilst it has been suggested in this paper that modern human sociality today is set apart from our environment since we no longer need to follow seasonal resource patches, we might have retained some form of connection to our prehistoric sense of seasonality. Some connection to our prehistoric seasonal movements remains with us perhaps today during the winter “seasons of collective effervescence” in the form of Christmas and New Year (Wengrow and Graeber 2015, 18).

![Figure 1 ref: A, Lancaster. (nd.) Early Medieval Wales. Available at: viking-5-wales-vikings-on-the-coast.jpg [accessed 17/02]](https://theposthole.org/sites/theposthole.org/files/styles/article_thumb/public/articles/506/Figure%201%20%281%29.jpg?itok=22FvdRE7)