When given the opportunity to review The Contemporary and Historical Archaeology Conference (CHAT) 2012, I decided I wanted to do more than simply describe this unique conference. The pervasive theme that struck me throughout the three days was the direct importance and relevance each talk had to modern day societies, ranging from discussions about roundabouts through to the Chernobyl disaster, and the material study of artefacts in charity shops. This was a unique conference, delivering an inescapable and striking analysis of certain aspects of modern day society, and asking poignant questions about the very manner in which we conduct archaeology. It is this relevance and uniqueness that I hope comes through in this review, which is by no means a comprehensive rhetoric of what was spoken about (a full timetable is available here http://tinyurl.com/ckgdjwj), but rather a brief overview of particular talks which stood out from what was overall a wonderful conference.

CHAT being held in York for the first time in its ten year history, allowed myself and fellow University of York students to listen to some of the greatest academics in Contemporary and Historical archaeology, for a mere £20. The conference was kicked off by York’s very own Kate Giles, with members of the CHAT 2012 organising team, led by York PhD student Hilary Patterson. From the off the conference was fun and lively, with Dr. Gabriel Moshenska using his enigmatic sounding “uncle benny” to reveal the value and importance of understanding that much of archaeology has close ties with the process of Reverse Engineering, where archaeologists investigate how and why objects have been made. Understanding that archaeology involves a process of working backwards from the final result, and that these steps are fraught with difficulty, emphasises the need to ask the right people the right questions. When deciphering the more recent past, which involves complex technologies, understanding these construction methods can often only be done through oral histories; talking to those who have knowledge and experience in this area (Moshenska 2012).

The archaeology of our relationship with the internet was the focus of the next talk. Much of our lives are spent online and there will be very few of those in the world of higher education who do not go online at least once a day, therefore it is essential to ask how can we understand the way in which this major presence in our lives changes the way we think and act about the world? Dr. Ross Wilson gave a presentation on evaluating the way online coding changes how consumers interpret the information being portrayed; the idea that one subtle change in coding can alter the way a website is perceived. We all use the internet, and I for one don’t think twice about the way information is being given to me, or the way that this changes my perception of it. Web analysis is not a new concept, however, little to no work has been done on evaluating the coding used to provide the information we rely on. This work encourages us to question “why is information being portrayed in this way?” and to contemplate the impact of unseen words on our everyday lives (Wilson 2012).

Outside this virtual world there are other constants that we all experience and yet barely ever consider, and Dr. Matt Edgeworth’s talk on the wonders of roundabouts discussed one of them. Ever since having a picnic on what is claimed to be the UKs first roundabout in Letchworth (Figure 1), I have held a soft spot for roundabouts, and my excitement was therefore palpable when given the opportunity to listen to Dr. Edgeworth and the notion of roundabouts as ‘Non-Places’; areas which are more often than not, devoid of activity (excluding the odd picnicker). Yet conversely, roundabouts are centres, which we revolve around. We have all experienced these places, yet never for themselves. We can see further examples of this notion such as motorways, hotel rooms and escalators, all of which are areas that we have experienced but never with an emotional link or significance. The question as to why these areas are not considered in this way are complex and it was not Dr. Edgeworth’s aim to answer these within his talk (for those interested, Marc Agué’s 2008 book Non-Places: An introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity is considered an excellent introduction), but rather to increase our awareness that when we view both our past and present landscapes, the way in which we interpret and understand space is by no means simple (Edgeworth 2012).

As well as observing roundabouts, most of us have discovered the sheer joy of charity shops, where you can find truly remarkable purchases for absurdly low prices. To this day the greatest purchase of my life remains a £2.99 coffee maker. It does however require an original perspective to take a charity shop and turn it into an archaeological site, this being exactly what Mr. Ralph Mills has done and what he presented to the audience in the second afternoon session of the conference. Mills is studying the materials left behind in charity shops and the purchases of shoppers, with fascinating results. The items that are bought from charity shops have undergone a remarkable change in perceived value over their lifetime. At one point they were considered valuable enough to be bought, then of little enough value to be given away for free, but not so worthless as to be thrown away. Yet they are still important enough to be displayed and valued by charity shops and valued enough by another to be purchased again. The importance we place on different items changes depending on whom we are and our experience with those items, but to what extent are these universal?

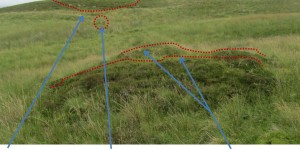

Mills has looked at the stock of charity shops (Figure 2) from varying socioeconomic areas and shown that there seem to be trends developing in certain areas as to the nature of materials being bought and sold. Mills has revealed how the study of artefacts in order to determine social status and social groups is as relevant today as it is to the past, even with the advent of mass production. It also allows us to understand regions on a different cultural level compared to that of the numerically driven system, such as average wage or house pricing. Understanding our current relationships with objects is an area of research that I would suggest has the potential to reveal much about the world we live in today, and the work here by Mills takes us a significant step closer towards this understanding (Mills 2012).

The final talk in this review was one of the most moving and interesting talks of the session; Robert Maxwell’s work on the Chernobyl exclusion zone provided a unique insight into possibly the most emotive region on earth. Maxwell’s field work has taken him to this unique part of the world to evaluate what physical changes have occurred to the town surrounding the nuclear power plant since its evacuation in April 1986. Understanding how the site has been used by graffiti artists, looters and those coming to perform remedial and observation work on the site all help to build up a picture of the way in which this now deserted town is being used. An understanding of the physical condition of the Chernobyl exclusion area, arguably the site of one of the most important events in the late 20th Century, gives us a unique insight into what happens when this form of disaster strikes (Maxwell 2012).

A review of a conference would not be complete without mention of the social joys that a conference such as this affords. The cheese and wine reception at Barley Hall led to some fantastic archaeological discussion, which possibly left me more confused than when we began, but was wonderful all the same; as was the opportunity to go for a meal with many of the delegates and speakers.

Whilst the purpose of this review is not to persuade people to come to next year’s CHAT, nor truly to win people over to the ‘side’ of Contemporary and Historical Archaeology, I nevertheless hope that it has shown the breadth offered within such a conference; from analysis of areas, including the use of space and the study of disaster zones, and things that we use every day, to a view on the way archaeology operates across many periods. This conference has allowed an insight into the present and the past that is relevant on a great number of levels, as well as simply being huge amounts of fun.

Bibliography

- Edgeworth, M. (2012) ‘Hubs of Super-Modernity: Roundabouts as Places and Non-Places’. [CHAT 2012]. University of York. 17th November 2012

- Maxwell, R. (2012) ‘An uncommon Horror: Dissonance and Decay in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone’. [CHAT 2012]. University of York. 17th November 2012

- Mills, R. (2012) ‘£0.99 Archaeology: Small Things Considered’. [CHAT 2012]. University of York. 17th November 2012

- Moshenska, G. (2012) ‘Reverse Engineering the Human Environment’. [CHAT 2012]. University of York. 16th November 2012

- Wilson, R. (2012) ‘Surveying New Sites: Archaeologies and Landscapes of the Internet’. [CHAT 2012]. University of York. 16th November 2012

Recommended further reading

- anon. nd. ‘CHAT 2012: The CHAT Olympiad - celebrating 10 years of contemporary and historical archaeology’. http://www.york.ac.uk/archaeology/news-and-events/events/conferences/cha... [Accessed 18th November 2012]

- Augé, M. (2008) Non-Places: An introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity (2nd Ed.). London: Verso