What is the Portable Antiquities Scheme?

The Portable Antiquities Scheme (often referred to as PAS) is a government-funded project intended to encourage members of the public to voluntarily record any artefacts they might find. Many of these finds come from metal detectorists, and a large part of the PAS’s job has been to engage this part of the community; but people also find objects when walking the dog, digging the garden, or in a host of other activities. The result is that thousands of artefacts are recovered annually, and these may now be recorded on a central database, accessible online (www.finds.org.uk) not only to professional archaeologists, but also to students, researchers, and interested members of the public. The PAS has been running since 1997 and, having started out as a pilot study of a small number of counties, today covers the entirety of England and Wales and has recorded over 800 000 individual objects.

I should declare an interest at this point. I am an ex-employee of the PAS, and very much an advocate for their work. Working with metal detectorists is not an uncontroversial business, and neither is it always easy, but it is rewarding, and most of all it is important. PAS data is changing the way we understand the archaeology of the country, and arguably in the last 10 years has had a greater impact on archaeology than any other innovation or organisation.

Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs) are locally based archaeologists who are the points of contact for members of the public and undertake recording on the database. Working as a Finds Liaison Officer within the PAS is a wonderful opportunity to work with local communities, get to grips with the archaeology of a region, and gain familiarity and experience with an extraordinary range of portable material culture (Figure 1). It also trains you to think on your feet, and provides an opportunity to become involved in some of the UK’s biggest archaeological news stories (cases such as the Staffordshire and Vale of York hoards put FLOs in newspaper articles across the country).

However, I said that it wasn’t always easy. Working with metal detectorists can be challenging, as there is often a mutual lack of trust which needs to be addressed. I have been called a liar, I have been threatened, and I have been undermined and cheated. But I have also met some of the most honest, hardworking and genuinely interested heritage enthusiasts you could care to meet. Some even see themselves as protectors of archaeology, rescuing material ahead of development. This diversity is important to understand; to paint all detectorists as troublemakers or thieves is a massive injustice.

So where does this mutual mistrust come from? There is a growing body of literature concerning this (see for example papers in Thomas and Stone 2008), but many of the problems come out of mistakes made in the past (on both sides) and a lack of communication. It is these issues that the PAS seeks to address. For many archaeologists, metal detecting should be illegal or heavily controlled by licenses, and the PAS is seen to somehow legitimatise illegal activity. However, in other countries, where more restrictive legislation is in place, detecting has remained difficult to control.

The twofold approach taken in England and Wales, then, is beneficial, as the vast majority of finds are recorded with the PAS on a voluntary basis, drawing on the diplomatic skills of the scheme’s FLOs, while a much smaller number of finds – referred to as ‘treasure’ – are subject to mandatory recording and must be reported to the coroner. These finds may eventually find their way into local or national museums.

Treasure

So what constitutes treasure? Any object that is made substantially of gold or silver and is over 300 years old is legally counted as treasure. Collections of coins (hoards) and prehistoric base-metal objects also qualify, and finders of such objects and assemblages have a legal obligation to report them under the Treasure Act 1996. The legal process is orchestrated through the national network of locally-based coroners, but in practice FLOs fulfil an invaluable service as go-betweens.

The PAS also offers advice on the treasure process, to finders, landowners, and archaeologists (gold and silver found on professional archaeological excavations is also subject to the requirements of the Treasure Act). It is also important to note that the situations in Scotland and Northern Ireland are very different to the situation in England and Wales. In Scotland, for instance, all archaeological objects must legally be recorded as Treasure Trove. This is undertaken outwith the PAS, though there is a close working relationship between the Scheme and its colleagues north of the border.

Archaeological Research

Whether we are talking about the elaborate jewellery, weaponry and hoards that make up the most famous treasure cases, or the more mundane artefacts of the everyday (which are very much the archaeologist’s bread and butter), the Scheme’s purpose is to record artefacts found by members of the public, in order that they might enhance archaeological knowledge.

This means that the data has to be recorded and stored on a database in such a way that it is useful for research, whether that is research on the distribution of settlements and other activities in the landscape, or on the detail of artefacts themselves. Therefore, we need to record artefactual detail precisely, comprehensively, and efficiently. For this task, FLOs are offered extensive training from experts in their respective fields, from prehistoric flints to post-medieval pottery, and with particular attention paid to metalwork and coins.

However, it also means that we need reliable findspot data. Data obtained from metal detecting is often said to be without context, but it is not without use, we just need to know how to treat it. We do not, for instance, argue that antiquarian finds are useless, and yet, thanks to the PAS, the data we have on metal-detected finds is often much better quality than this. Of course, we have to take care when working with this data, but over the years FLOs have been able to build up close working relationships with detectorists they can trust, meaning that high resolution grid-reference data is often available. Indeed, a key role of the FLO is to educate detectorists as to best practice, and to explain why good findspot data is so important to us.

The PAS database is available to the public, but privileged access to further information can be gained for those working on research projects (including undergraduate and postgraduate dissertations). Indeed, over the years a number of important studies into PAS data have been undertaken. Early on, the key concern was to establish the degree to which PAS data could be considered robust: did it really reflect patterns of settlement and activity in antiquity, or was it biased by the areas in which people went detecting, or the clubs to which FLOs had access (see Robbins 2011 for an up-to-date survey of these issues)?

Once successfully completed, these studies allowed more focused cultural, social, and economic questions to be addressed, and we are now beginning to see the full fruits of this (see papers in Worrell et al. 2010). Key studies include Brindle’s (2011) study of Roman finds and sites in England, Walton’s (2010) study of Roman coin loss (see also Walton and Moorhead 2011), and the VASLE project, carried out under the direction of Julian D. Richards (Naylor and Richards 2005, Richards and Naylor 2009, Richards et al. 2009).

More recently, Jane Kershaw has undertaken research on Viking-Age gender, migration, and culture contact, using PAS records of female jewellery (Kershaw 2009; Kershaw forthcoming), and is now working on the Viking-Age ‘bullion economy’. We have also started to build a team of researchers working on early-medieval data at the University of York: Alison Leonard is using PAS data to consider patterns of settlement in Viking-Age Lincolnshire; Rob Webley is working on an project funded by the Arts and Humanties Research Council (AHRC) to characterise the material culture of the Anglo-Norman transition; and the Torksey project, spearheaded by Julian D. Richards and Dawn Hadley (see http://www.york.ac.uk/archaeology/research/current-projects/torksey/) also draws heavily on PAS and other metal-detected data in characterising the site of a supposed Viking winter camp.

Engaging Communities

As we have seen, the PAS has a remit to record the public’s finds for the particular purpose of enhancing archaeological knowledge. However, it also has the important effect of bringing members of local communities into contact with museums and archaeologists, and helping them to understand and engage with their own local heritage. Indeed, the PAS was originally thought of as Britain’s largest community archaeology project, though it now tends to be considered more in terms of a gateway to public archaeological knowledge.

Nonetheless, the PAS continues to provide opportunities for volunteers to work with finds, as well as providing a mechanism whereby its employees can play a role in education, whether through events such as those planned as part of English Heritage’s Festival of History, through visits to schools, scout meetings, working men’s clubs, local societies and retirement homes, or through more informal channels.

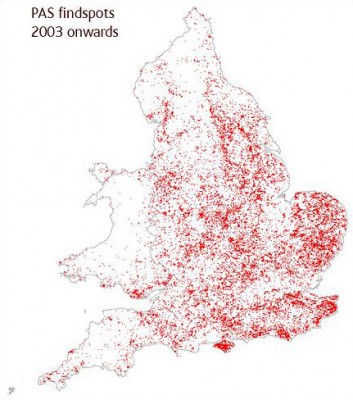

Despite its relative youth, the potential of the PAS is already being realised. Thus far, much work has been done on Roman material; though recent years have seen an increasing focus on the early-medieval period (staff and students at York have played a large part in this drive). This work has begun to demonstrate just what is possible; distribution maps of early-medieval finds look radically different before and after PAS; all of a sudden we have data from the countryside, rather than just relating to urban excavations and road building schemes (see Figure 2 for a taste of just how much the PAS has ‘opened up’ England’s rural past). A large number of research projects already draw upon PAS data (see http://finds.org.uk/research/projects/index/level/3/), but there is still plenty of opportunity for further work, particularly with late medieval and post-medieval finds.

If you would like to find out more about the PAS, as a provider of volunteering and employment opportunities, as a resource for research, or even just as a way of investigating the heritage of your local area, please visit www.finds.org.uk.

Bibliography

- Brindle, T. (2011) ‘The Portable Antiquities Scheme and Roman Britain: an assessment of the potential for using amateur metal detector finds to study the past’. PhD Thesis, Kings College London

- Kershaw, J. (forthcoming) Viking Identities: Scandinavian Jewellery in England. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Kershaw, J. (2009) ‘Culture and gender in the Danelaw: Scandinavian and Anglo-Scandinavian brooches’. Viking and Medieval Scandinavia. 5. 295-325

- Naylor, J. D. and Richards, J. D. (2005) ‘Third party data for first class research’. Archeologia e Calcolatori. 16. 83-91

- Richards, J. D. and Naylor, J. (2009) ‘The Real Value of Buried Treasure. VASLE: The Viking and Anglo-Saxon Landscape and Economy Project’, in S. Thomas and P. Stone (eds.) Metal Detecting and Archaeology. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer

- Richards, J. D., Naylor, J. and Holas-Clark, C. (2009) ‘Anglo-Saxon landscape and economy: using portable antiquities to study Anglo-Saxon and Viking Age England’. Internet Archaeology. 25

- Robbins, K. (2011) ‘An analysis of the distribution of Portable Antiquities Scheme data’, PhD Thesis, Southampton University

- Thomas, S. and Stone, P. (2008) Metal Detecting and Archaeology (Heritage Matters). Woodbridge: Boydell

- Walton, P. (2010) ‘Analysis of coin use and loss in Roman Britain based on PAS data’, PhD Thesis, University College London.

- Walton, P. and Moorhead, S. (2011) ‘Roman coins recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme: a summary’. Brittania. 42. 432-437

- Worrell, S., Egan, G., Naylor, J., Leahy, K. and Lewis, M. J. (2010) ‘A Decade of Discovery. Proceedings of the Portable Antiquities Scheme Conference 2007’. British Archaeological Reports, British Series. Oxford: Archaeopress. 520