This paper re-evaluates a rock painting from Oxtotitlán Cave in Guerrero, Mexico as a toponym (place-sign). The resulting analysis finds a close correspondence between this composition and toponyms from Middle Formative period greenstone objects. It also suggests that one possible interpretation of the toponym is as a reference to the nearby archaeological site of Cerro Quiotepec.

This report touches on an area of considerable interest in the study of ancient Mesoamerican writing systems: the development of emblems or graphic images, which join distinct elements into meaningful arrangements but do not directly codify any specific set of sounds, in Olmec-style art and writing. While the degree of phoneticism present in Olmec iconography is a fascinating question that remains unresolved (see Pohl et al. 2002; Rodríguez Martínez et al. 2006), several recent papers have discussed the ideographic nature of these signs, using numerals (Justeson 1986; Sedat 1992), various icons and synecdochic signs (Houston 2004; Justeson 1986, 1990) and toponyms or place-signs (Brotherston 1999; Houston 2004). This paper draws attention to the existence of another possible example of a Middle Formative period (900-500 BC) toponym from Oxtotitlán Cave in the state of Guerrero in Mexico (Figure 1).

Oxtotitlán is a limestone cavern located approximately half-way up a hillside situated to the east of Cerro Quiotepec and about 1 km from the town of Acatlán, to the north of the city of Chilapa. It consists of two large grottoes. To date, over a dozen black paintings have been found in the Oxtotitlán’s north grotto; two polychromatic murals have been documented on the cliff face between and above the two grottoes, and three panels of red paintings are known to exist in the cave’s south grotto (Grove 1968, 1969, 1970a, 1970b; Lambert 2012) (Figure 2).

Both the murals and the black rock paintings appear to depict images of rulers, felines and serpents using the iconography of Olmec-style art (Grove 1970a; Grove 1970b). Although some of the red paintings, such as Painting A-3, are reminiscent of Classic and Postclassic period depictions of rain gods (Grove 1970b, 26), the majority of the rock paintings in the south grotto form geometric designs. Only a few of the red rock paintings appear to have iconographic features frequently found in Olmec-style art, including the possible toponym, Painting A-1.

Known locally as “El Diablo”, Oxtotitlán Painting A-1 was first described by David Grove (1970a, 5; 1970b, 25). Based on his own observations and a later reconstruction painted by Felipe Dávalos (Grove 1970a, 68, Figure 20; 1970b, 25, Figure 25), Grove noted that this rock painting combined four distinct images or signs.

At the top, he observed a hand-like element followed by a series of curvilinear lines and a small X-shaped motif underneath. Below these elements, he found a larger circular design with four petaloid extensions and a negative X-shaped motif. Finally, at the bottom of the painting, Grove detailed a double-scroll motif. Interestingly, Grove was the first to perceive a connection between this aspect of Painting A-1 and the Late Postclassic “tepetl” (mountain) glyphs from codices of the Central Highlands of Mexico but did not pursue this line of inquiry. This is unfortunate since the number of Early-to-Middle Formative period ideographic signs and images attributable to an early or proto-writing system related to Olmec iconography are few and the recognition of a new example of a toponym from such an early date would be a welcome addition to the epigraphic work of Mesoamerican scholars.

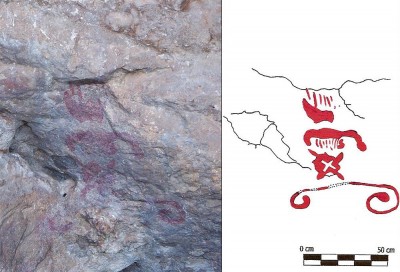

My own examination of Painting A-1 began in January 2010 with a visit to Oxtotitlán Cave. My analysis entailed a re-evaluation of the elements that made-up the rock painting since all currently used representations of Painting A-1 rely on the idealised reconstruction created by Dávalos and Grove (e.g. Joralemon 1971, 66, Figure 190). Several colour photographs were taken of the rock painting (Figure 3) using only the optical lens of a Kodak Z712 IS digital camera and a full-colour tracing was made from these photographs (Figure 4) to more accurately display the details of the composition.

Even with these efforts, the rock painting proved to be too badly eroded to get a clear sense of all of its elements. Nevertheless, enough details were revealed to permit a thorough comparison between Oxtotitlán Painting A-1 and other known Formative period toponyms to demonstrate how this rock painting functioned as a place-sign. Based on recent breakthroughs in the study of Mesoamerican place-signs (Brotherston 1999; Byland and Pohl 1994; Marcus 1983; Whittaker 1993), further comparisons with the Postclassic period and historical place-signs and place names from Guerrero will also be attempted in an effort to offer a plausible reading for this toponym. I will begin with a new description of Painting A-1 based on my photographic re-examination of the rock painting.

Oxtotitlán Painting A-1 as an Early Toponym

Painting A-1 consists of at least three, possibly four, different images painted in red pigment and organised in a vertical manner (see Figure 4). At the top of the rock painting, there are two badly eroded elements. The first is a triangular motif with six linear projections extending upwards. Directly underneath this element there is a large comb-like design which is broadly shaped like an upside-down “U”. Beneath this U-shaped element, there are at least eight linear projections pointing downwards next to a small curvilinear S-shaped element. This comb-like design is followed by the floral image consisting of a rounded design with four points and an additional four petaloid projections. Within this design, there is a negative X-shaped element. At the bottom of the rock painting, there is a scroll-like element. It consists of a straight line ending in two inward-facing curls on each side.

By themselves, each of these elements may have correspondences to motifs found elsewhere in Olmec-style art (Joralemon 1971, 14-15). For example, the triangular element may be an example of motif #97 in Joralemon’s classification system, or miscellaneous vegetation; while the X-shape is suggestive of motif #99, or the crossed band; and the scroll-like element is reminiscent of motif #136, or a bar with curled ends. However, when compared to the two known examples of Formative period Olmec-style place-signs from Guerrero (Houston 2004, 285, Figures 10.4a and 10.4b), an incised greenstone celt from an unknown provenience (Figure 5a) and an incised tablet from Ahuelican (Figure 5b), the structural and iconographic similarities are striking.

All three examples contain a scroll motif at the bottom of each design. Although sometimes referred to as a representation of the surface of the earth (Reilly 1995, 35), I believe it is more likely that, like its Postclassic counterparts from the Codex Mendoza (see Figures 5h and 5i), the scroll-like motif may have served to symbolise the base of the mountain as a cave opening. The intimate relationship between the scroll-like motif and the mountain theme is best demonstrated in the tablet from Ahuelican where a stepped design similar to the mountain signs of Monte Albán (Figure 5f), Cacaxtla (Figure 5d) and Xochicalco (Figure 5e) is directly attached to the scroll. A similar relationship is made quite explicit in Chalcatzingo Monument 1 albeit from a slightly different angle (Figure 5c). Here, a zoomorphic mountain (covered with plants) opens its giant maw thereby creating a large cave.

In addition, all of the Formative period place-signs under consideration organise their component images or signs in the same manner. Interestingly, this structural sequence is repeated in many later toponyms. The scroll motif or mountain sign is located at the bottom of the place-sign and serves as a general locative. Based on a standardised image of a mountain in profile, the mountain sign (glossed as “tepetl” in Nahuatl and “yucu” in Mixtec) typically features a triangular shape, often stepped, with either a flat or curvilinear scroll-like base (Brotherston 1999; Pohl 2004). Its exact identification is then specified by other images or signs representing relevant geographic information specific to the locale being portrayed by the toponym, such as rivers, flora, or fauna. Depending on the place-sign, these can be situated above the mountain sign, inside it, or both (compare Figures 5d and 5h). In the case of Painting A-1, the elements are arranged vertically, one on top of the other. This is not the situation with the incised tablet from Ahuelican. Here, there appears to be a salient image inside of the mountain sign.

Clearly, “reading order” can have an effect on the meaning of the individual signs in Formative period toponyms. However, it is also important to note that these images or signs may, in turn, represent truncated versions of larger entities. Take the greenstone celt from Guerrero as an example (Figure 5a). This place-sign contains a mountain sign along with representations of part of a leg and a headdress. Using the principle of synecdoche (pars pro toto), it is probable that these images represented a larger concept such as “lord” or “royalty”. To help decipher these synecdochic signs, it is crucial to consider the overall context of each element in a place-sign. For instance, in both Painting A-1 and the greenstone celt, the scroll-like motif appears without the rest of the mountain sign, but its structural position in the overall composition of the toponym suggests that it stood for the entire mountain sign.

Putting all three of these observations together, it is now possible to identify Oxtotitlán Painting A-1 as a compound toponym or place-sign which consisted of at least three distinct images, each a common motif in Olmec iconography. The scroll-like design at the bottom of the rock painting is a synecdochic representation of a generic mountain sign. On top of this sign is located a floral design decorated with a crossed band. This sign is surmounted by a badly eroded set of triangular and comb-like designs which may also have had some vegetal connotations (Joralemon 1971, 66). Given the structural similarities between Painting A-1 and other recognised Formative period toponyms from Guerrero, it appears that these signs may have served to specify the location based on geographically relevant features. The question remains, however, which location is being identified by the toponym in Painting A-1?

When examining possible readings of Painting A-1 as a place-sign, two different methodologies may be used. The first and most commonly used method to identify the place referenced by a toponym is to compare it to place-signs from the same region whose names have been transcribed and to compare their constituent signs. Most often the Aztec and Mixtec codices of the Late Postclassic period and Early Colonial period present the best sources of information for establishing and cross-checking possible readings.

Although there is some potential for disjunction or variances in the meaning or construction of a place-sign over time and between cultures (Whittaker 1993, 14-20), several scholars have noted that Mesoamerican toponyms have been incorporated into a variety of phonetic scripts since the Formative period without significant changes in their constituent parts (Brotherston 1999, 53-57; Marcus 1983, 107) (compare Figures 5f and 5g with Figures 5h and 5i).

In a case where historically-known toponyms are not available for comparison, a second method may be used to relate place-signs to a specific location. Pioneered by Bruce Byland and John Pohl in the Nochixtlan Valley of northern Oaxaca (Byland and Pohl 1994; Pohl and Byland 1990; Pohl 2004), this approach relies on matching archaeologically-known ruins discovered through site surveys and locally-known place names with the imagery of unidentified toponyms. To narrow down the parameters of such a search, this methodology presumes that unidentified toponyms juxtaposed next to known toponyms in a codex, or other source, may refer to sites found in close proximity to those associated with known toponyms (Pohl 2004, 226-232).

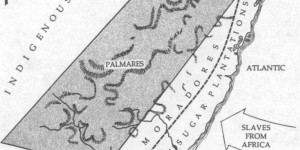

Although Late Postclassic and Early Colonial period codices such as the Matrícula de Tributos offer a plethora of place signs for Guerrero (see for example Barlow 1949), from Tlapa to Tlaxco and from Quiyahteopan to Cihuatlan, only one, Tepecoacuilco, has a mountain sign, but does not have any other signs that correspond to those found on Painting A-1. Given the lack of comparable place-signs from nearby regions of Guerrero, I believe that it may be worthwhile to examine local place names as a possible source for the toponym in Painting A-1. One option that readily comes to mind is Cerro Quiotepec (Figure 6).

Located a few hundred metres to the east of Oxtotitlán Cave, Cerro Quiotepec contains a large number of surface sites with Middle and Late Formative period ceramics, some with an estimated population of 300-500 people (Schmidt 2005). It has also been noted that surface ceramics dating from the Formative period through the Postclassic period are present throughout the valley between Oxtotitlán and the sites on Cerro Quiotepec, suggesting that these two locales formed part of a single community over several millennia. If this is the case, it is possible that the place names used today may be similar to those that were employed by local inhabitants over 2500 years ago, and that these may have been reflected in the Middle Formative period place-sign depicted in Painting A-1.

Originally identified as “Cerro Quiatepec” and transcribed as the “the hill or mountain of rain” from the Nahuatl words QUIAHUITL (“rain”) and TEPETL (“mountain”) (see Grove 1970b, 31), the correct toponym “Cerro Quiotepec” (see Schmidt 2003, 2005) means something quite different in Nahuatl. It is can be transcribed as QUIOTL or QUIYOTL (“the flowering stem or stalk of the maguey plant”) (Gates 2000, xxxiv; Siméon 1977, 430) and TEPETL (“mountain”) or “the mountain where the flower of the maguey plant grows.” Following this description, the key to attributing the toponym in Painting A-1 to Cerro Quiotepec would be the presence of secondary signs within that place-sign which pertain specifically to maguey, flowers or stems.

A significant degree of resemblance between the place name and the place-sign can be seen in the floral design which serves to qualify the scroll or mountain sign in Painting A-1. The identification of the badly eroded elements on top of the rock painting is much more difficult and must be regarded as extremely tentative. Nonetheless, it is possible to view these designs as references to a maguey by cross-checking them with depictions of these plants in transcribed toponyms from historical sources.

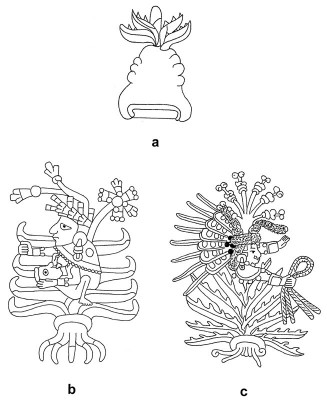

One probable cognate occurs both in the Early Colonial period Mapa de Cuauhtinchan, Núm. 2 (Yoneda 2005, 44-45) and on page nine of the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt 1992) in reference to a town in the state of Mexico known as “Metepec” or “the mountain of maguey”. In these examples, the maguey plant is realistically shown with its fleshy leaves and marginal spines pointed upwards (Figure 7a), recalling the triangular design with its upward-projecting elements in Painting A-1.

Similar depictions of maguey are also found in portrayals of Mayahuel, the Aztec goddess of maguey, in some of the Late Postclassic codices of central Mexico. For instance, on page 28 of the Codex Fejéváry-Mayer (1971) (Figure 7b) and on page six of the Codex Borbonicus (1974) (Figure 7c), Mayahuel is pictured in the midst of a maguey plant which has features comparable to the eroded design in Painting A-1. It is characterised by fleshy leaves, sometimes with marginal spines, pointed upright and has a series of roots emanating from an opening with inward curled ends which is reminiscent of the comb-like motif in the rock painting. Moreover, in both images, the maguey is depicted with quiotes or flowering stems while the illustration of Mayahuel in the Codex Fejéváry-Mayer (Figure 7b) clearly shows an X-shaped flower similar in overall form to the floral design from Painting A-1.

Although far from conclusive, when taken together these various strands of evidence offer strong circumstantial support for the interpretation of Painting A-1 as a place-sign for Cerro Quiotepec whose components signify the following concepts (in order from top to bottom): maguey – flower – mountain.

Conclusions

The recognition of a toponym from Oxtotitilán Cave adds to the corpus of known place-signs from the Middle Formative period (900-500 BC) in Guerrero, Mexico. At the same time, it suggests that this cave was more than just a ritual centre associated with agricultural fertility and rainfall (Grove 1970b, 31). Indeed, the presence of a toponym at Oxtotitlán opens up the possibility that there may have been a historical component to the rituals enacted in the cave. These ritual practices may have involved the recitation of dynastic histories, origin myths, stories of migration, or other narratives requiring a perception of place that persisted over long periods of time.

Although the reading of the place-sign in Painting A-1 as referencing Cerro Quiotepec is somewhat tenuous given the poor preservation of parts of the rock painting, the iconographic correspondences, comparisons with Nahuatl place names, and archaeological associations are quite suggestive; thereby making a strong case for the importance of clarifying the archaeological context of all early examples of writing in Mesoamerica whenever possible.

Notes

- Figure 5 - (a) an incised greenstone celt from Guerrero (redrawn after Coe et al. 1995, 231); (b) the incised tablet from Ahuelican, Guerrero (redrawn after Coe et al. 1995, 234); (c) Chalcatzingo Monument 1 (Morelos, Mexico); (d) Cacaxtla mountain glyph (Tlaxcala, Mexico) (redrawn after Piña Chan 1998, 44, Figure III.2.d); (e) Xochicalco Stela 2, Structure A (Morelos, Mexico) (redrawn after López Luján 2001, 132); (f) Monte Albán II Tototepec place-sign from Building J (Oaxaca, Mexico) (redrawn after Marcus 1983, 108, Figure 4.15); (g) Monte Albán II Ocelotepec place-sign from Building J (Oaxaca, Mexico) (redrawn after Marcus 1983, 108, Figure 4.15); (h) Tototepec place-sign from the Codex Mendoza (redrawn after Marcus 1983, 108, Figure 4.15); and (i) Ocelotepec place-sign from the Codex Mendoza (redrawn after Marcus 1983, 108, Figure 4.15).

- Figure 7 - (a) the tepetl place-sign for Metepec from the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt 1992); (b) Mayahuel, the Aztec goddess of maguey, from the Codex Fejéváry-Mayer (1971); and (c) Mayahuel from the Codex Borbonicus (1974).

Bibliography

- Barlow, R. (1949) The Extent of the Empire of the Culhua Mexica. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Berdan, F. and Anawalt, P.R. (1992) Codex Mendoza. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Brotherston, G. (1999) ‘Place Signs in Mesoamerican Inscriptions and Codices’, in W. Bray and L. Manzanilla (eds.) The Archaeology of Mesoamerica: Mexican and European Perspectives. London: British Museum Press. 50-67

- Byland B. and Pohl, J.M.D. (1994) In the Realm of Eight Deer: The Archaeology of the Mixtec Codices. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

- Codex Borbonicus (1974) Codices Selecti. 44. Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck-u, Verlagsanstalt

- Codex Fejéváry-Mayer (1971) Codices Selecti. 26. Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck-u, Verlagsanstalt

- Coe, M.D., Diehl, R.A., Furst, P.T., Reilly, F.K., Schele, L., Tate, C.E. and Taube, K.A. (1995) The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Harry N. Abrams

- Gates, W. (2000) An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552. New York: Dover Publications

- Grove, D.C. (1968) ‘Murales Olmecas en Guerrero’. Boletín del Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia. 34. 11-14

- Grove, D.C. (1969) ‘Olmec Cave Paintings: Discovery from Guerrero, Mexico’. Science. 164 (3878). 421-423

- Grove, D.C. (1970a) ‘Los Murales de la Cueva de Oxtotitlán, Acatlán, Guerrero. Informe sobre las investigaciones arqueológicas en Chilapa, Guerrero, noviembre de 1968’. Serie Investigaciones. 23. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia

- Grove, D.C. (1970b) The Olmec Paintings of Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero, Mexico. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology. 6. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks/Trustees for Harvard University

- Houston, S.D. (2004) ‘Writing in Early Mesoamerica’ in S.D. Houston (ed.) The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. 274-309. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Joralemon, P.D. (1971) A Study of Olmec Iconography. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology. 7. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

- Justeson, J.S. (1986) ‘The Origin of Writing Systems: Preclassic Mesoamerica’. World Archaeology. 17 (3). 437-458

- Justeson, J.S. (1990) ‘Evolutionary Trends in Mesoamerican Hieroglyphic Writing’. Visible Language. 24 (1). 88-132

- Lambert, A. (2012) ‘Three New Rock Paintings from Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero’. Mexicon. 34. 20-23

- López Luján, L. (2001) ‘Xochicalco: El Lugar de la Casa de las Flores’, in L. López Luján, R.H. Cobean and A.G. Mastache de Escobar (eds.) Xochicalco y Tula. Milan, Italy: Jaca Book. 14-141

- Marcus, J. (1983) ‘The Conquest Slabs of Building J, Monte Albán’, in K.V. Flannery and J. Marcus (eds.) The Cloud People: Divergent Evolution of the Zapotec and Mixtec Civilizations. 106-108. New York: Academic Press

- Piña Chan, R. (1998) Cacaxtla: Fuentes Histórica y Pinturas. Mexico City: Fondo Cultura Económica

- Pohl, J.M.D. (2004) ‘The Archaeology of History in Postclassic Oaxaca’, in J. Hendon and R.A. Joyce (eds.) Mesoamerican Archaeology. 217-238. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing

- Pohl, J.M.D. and Byland, B. (1990) ‘Mixtec Landscape Perception and Archaeological Settlement Patterns’. Ancient Mesoamerica. 1. 115-131

- Pohl, M.E.D., Pope, K.O. and Von Nagy, C. (2002) ‘Olmec Origins of Mesoamerican Writing’. Science. 298. 1984-1987

- Reilly, F.K. (1995) ‘Art, Ritual and Rulership in the Olmec World’, in M.D. Coe, R.A. Diehl, P.T. Furst, F.K. Reilly, L. Schele, C.E. Tate, and K.A. Taube (eds.) The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Harry N. Abrams

- Rodríguez Martínez, M.C., Ortíz Ceballos, P., Coe, M.D., Diehl, R.A., Houston, S.D., Taube, K.A. and Calderón, A.D. (2006) Oldest Writing in the New World. Science 313: 1610-1614

- Schmidt, P. (2003) Surface Archaeology in the Chilapa-Zitlala Area of Guerrero, México, Season I. FAMSI Grantee Report. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. Available at http://www.famsi.org/reports/02009/index.html [Accessed 7th June 2010]

- Schmidt, P. (2005) Surface Archaeology in the Chilapa-Zitlala Area of Guerrero, México, Seasons 2 and 3 (2004-2005). FAMSI Grantee Report. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. Available at http://www.famsi.org/reports/03015/index.html [Accessed 29th December 2012]

- Sedat, D.W. (1992) ‘Preclassic Notation and the Development of Maya Writing’ in E.C. Danien and R.J. Sharer (eds.) New Theories on the Ancient Maya. 81-90. University Museum Symposium Series, No. 3. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, University Museum

- Siméon, R. (1977) Diccionario de la Lengua Náhuatl o Mexicana. Mexico City: Siglo XXI Editores

- Whittaker, G. (1993) ‘The Study of North Mesoamerican Place Signs’. Indiana. 13. 9-38

- Yoneda, K. (2005) Mapa de Cuauhtinchan, Núm. 2. Mexico City: Editorial Miguel Angel Porrúa