Django Unchained has been nominated for five Oscars. However, the significance of the film goes beyond its technical and visual triumphs. It was a powerful intervention in what is probably the most resilient anxiety of slavery discourse: what is the appropriate way to represent the people and events involved in the era?

This representational malaise is unsurprising. Danielle Allen, in a thought-provoking analysis of the dynamics of American racism since the 1950s, discusses the ‘fossilized boundaries of difference’ that create interracial distrust in the United States today (Allen 2004, XIII). These boundaries are of the dead hand of history, the ‘solidification of the ideas of majority and minority’ that continue to put ethnic groups into a position of permanent ‘reduced political power’ (Allen 2004, 162). This has created levels of interracial distrust that hinders the functioning of American democracy.

Such arguments are now quite common among academics and it is precisely this disquiet that makes the question of the relationship between the representation of slavery and contemporary thinking so important.

The Haitian Revolution

Django Unchained is set in 1858, just before the US Civil War, a fact that the film reminds viewers of in the opening credits. In fact, the impending war between North and South seems to take on its own character in the film. The German dentist-assassin repeatedly advises Django that he would be better off getting to the North as soon as he can as opposed to, say, Mexico, which is geographically closer to Mississippi (where most of the film is based). Mexico had been free of slavery since 1829 (Agorsah 2010, 340) and Django would have been in no danger of legal harassment. A powerful counter-study to this providentialism is the case of the Haitian Revolution and its subsequent treatment by imperial powers.

In 1791 a slave insurrection began a conflict that lasted until the proclamation of independence in 1804 (Trouillot 1995, 89). This conflict was intertwined with the long war in Europe that ended at Waterloo; and yet, the Haitian Revolution was not a periphery struggle: Napoleon lost nineteen generals, including his brother-in-law, and both France and England lost more men in the fight for imperial control of the island than they did at Waterloo (Trouillot 1995, 99). Moreover, the Haitian Revolution ended French hopes for an American empire, forcing them to sell Louisiana to the United States in 1803 (Trouillot 1995, 100).

Despite this, the treatment of the revolution has been marginalising and trivialising. Even Eric Hobsbawm, a historian notable for his politically-informed studies, was able to write a book ‘entitled The Age of Revolutions: 1789-1843, in which the Haitian Revolution scarcely appears’ (Trouillot 1995, 99). Trouillot explains this as a consequence of the limited reach of Enlightenment categories, suggesting that this highly progressive revolution which made concrete steps towards the liberty of even Africans (who made possible the prosperity of white elites) was ‘the ultimate test to the universalist pretensions of both the French and the American revolutions’ (Trouillot 1995, 88). Trouillot’s close interrogation of contemporary literature exposes how the notion of a right to a modern black state was almost unthinkable. The slave uprising must be the consequence of ‘Royalist, British, mulatto, or Republican conspirators’ (delete to preference) and, of course, if black leadership was imposed temporarily it would lead only to chaos (Trouillot 1995, 93).

It would be offensively romantic to assume that a perfect order was created in Haiti, but the degree to which even a modest space of freedom was mentally disavowed and physically attacked is vital to understand the representation of slavery and liberty. This is best encapsulated by the fact that fifty years after independence Haiti was only able to gain international recognition by agreeing to pay France a very substantial indemnity. This was a debt paid to France so that the latter could acknowledge its own military defeat, itself a powerful testimony to the extent that imperial powers were able to de-legitimise ‘free states’ through the traumatic legal system of international recognition (a theme taken up by legal anthropologist Mieville in his thorough 2005 book Between Equal Rights).

This ideological context is similar to the one excavated in Leone’s (1984) paradigmatic account of the William Paca Garden. Paca was a notable American revolutionary whose name can be found on the Declaration of Independence (Leone 1984, 33). However, Paca’s wealth derived from slaves (of which he ‘owned’ over one hundred). The tension between the republican philosophy of independence and the actual treatment of non-white people was a recurring force in early American politics (see Guyatt 2009).

Leone posits that the geometry of the Paca garden served to naturalise the ‘arbitrariness of the social order’ by creating an illusion of fluidity and free movement while in reality controlling movement through carefully calculated pathways and sight-ways (Leone 1984, 33-34). In Leone’s study, if you find yourself walking through the Paca Garden then you will internalise the assumptions behind the design; that there is a natural order, a mathematical hierarchy, to the world of man.

New archaeologies

Yet, there is something about Leone’s study that jars; it feels very jaundiced and one-sided. If ideology were truly so efficient there would be no social unrest and no political shifts. Archaeologist Mary Beaudry (1990, 118) has produced a critique of Leone’s work in a review of a co-edited book on historical archaeology, criticising his reliance on a ‘Dominant Ideology’ narrative which displaces other approaches to the past. This criticism chimes with the work of postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak, author of the pivotal paper ‘Can the subaltern speak?’ from which this article quite crudely takes its title.

Spivak, broadly speaking, argues that intellectual production is ‘complicit with Western international economic interests’ (Spivak 1988, 271). Particularly interesting is her analysis of the tendency towards what she calls ‘catachresis’, here meaning an inappropriate usage of master categories such as ‘worker’ or ‘woman’ (Spivak 1988, 271). These tend to be derived from Eurocentric analytical models, and usually end up internalising ‘Asia’ or ‘Africa’ into a singular broad sweep path of development that mirrors that of Europe. Hence, even while the ‘benevolent intellectuals’ seek to use Marxist tools of analysis to liberate the subaltern they act to silence them.

This analysis of imperialist intellectual discourse is also present in a less developed form in Trigger’s (1984) perceptive article which refers to the practice of archaeology directly. Most importantly, what results from both of these analyses is that the subconscious concern for the preservation of the Western subject is a symptom of a global hierarchy, as opposed to personal inadequacy on the part of intellectuals. Consider Spivak’s (1988, 308) final passage:

‘There is no virtue in global laundry lists with “woman” as a pious item… The female intellectual as intellectual has a circumscribed task which she must not disown with a flourish.’

What special role can archaeology as a discipline play in this circumscribed task, the difficult process of teasing out better and better representations of the subaltern? One answer is exemplified by Ann Stahl (2008) in her work on taste in the Banda area of Ghana. She looks towards the ‘embodied forms of practical knowledge’, evident in shifts in style and context of material culture to understand how taste shapes and is shaped by economic and political factors (Stahl 2008, 827). The empirical focus here is on objects as opposed to structures, the theoretical focus on process rather than abstract ‘meaning’ as such. This critique of meaning relates to Spivak’s (1988) critique of intellectual catachresis, it is a criticism of logocentrism – a ‘scholastic fallacy’ which Bourdieu unpacks:

‘Projecting his theoretical thinking into the heads of acting agents, the researcher presents the world as he thinks it… as if it were the world as it presents itself to those who do not have the leisure (or the desire) to withdraw from it in order to think it’ (Bourdieu cited in Stahl 2008, 829).

A knowledge that is practical and patched together through changing social habits and practices is prioritised over a less mobile sense of meaning. The focus on practice theory seems to demand the following of archaeology:

- A re-appreciation of the ‘small things forgotten’ that might be situated in the ongoing Material Turn.

- A rejection of logocentric accounts that privilege has a singular and catachretic ‘meaning’ (for example, “this coat symbolises Christian values” is logocentric as opposed to “this coat is handed by Christians to the colonised to instil a sense of morality in them, where it is re-contextualised as embodying warrior prowess by the colonised who wear them in place of their original garments when marching to war”).

- An appreciation of the construction of context-specific knowledge as a locus of study.

Maroons forgotten, a fragmented freescape

I would be tempted to suggest that these new theoretical focuses are an attempt by archaeologists to personalise theory, to make it adapt to the characteristics of the subject rather than the other way around. Even with the advent of contemporary archaeology, which is able to utilise the thoughts of observers, it is clear that our expertise lies in materiality. Practice theory strikes me as being a quite conscious re-orientation towards this. One area where we can play to our strengths is with the everyday lives of the constituents of slavery.

From the early days of Hispaniola until after the Civil War the New World economy was structured around the slave trade and its offspring. This is a well known fact, one that most commentators are willing to decry and judge, and yet the surprising facts of uprising and resistance are not much discussed. Kofi Agorsah (2010, 333) has provided an overview of these ‘partnership-in-arms for freedom’ which range from the United States to Brazil, Jamaica to Mexico.

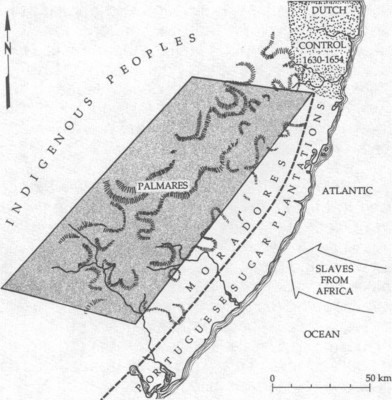

The first, obvious point to make is that there was no archetype maroon. Perhaps a typology of sorts might be fleshed out, but like all typologies of dynamic societies it is likely to prove to be a conservative force when new evidence and new thinking challenges previous conceptions. Instead, writers like Charles Orser (1994, 5) have rightly emphasised their position in the global political economy, a level of connectedness to ‘other’ societies which has been brought out by the evidence (and see Figure 1).

These were not merely groups of runaways that became isolated, and so a culture-by-culture typology would be too blunt. On this point the documentary evidence is quite interesting. Although many of the contemporary accounts were indeed trivialising or just generally incorrect about the motives and actions of the Marooners – for example, lying about the size of settlements and claiming to have destroyed them (Orser 1994) – there is evidence of a number of treaties between the free communities and European powers (see Agorsah 2010, 337-342).

Beyond treaties and trivialisation, the archaeological evidence has started to splash down a portrait of a general organisational form quite unique to maroons. Many of these maroons were in fact significant polities. Palmares in northern Brazil is the most excavated, with the evidence suggesting a population of around 20,000 in the late 17th century, a population that rivalled the greatest settlements of the region and included around a third of the slaves in the colony (Funari 2010, 367).

To add more to this landscape perspective, excavations show that where they were not ‘guerrilla’ forces (which are more problematic to study, see the challenges faced at St. Croix in Norton 2007) the Maroon people militarised the landscape, making it a defensive cultural artefact, as with stone fortifications at Nanny Town in Jamaica (Agorsah 2010, 341).

The numerous villages that made up Palmares are all consciously oriented towards the River Mundau, which colonial troops would have sailed upon to launch attacks on the capital (Funari 2010, 366). Still, Maroons were not merely survivalist camps. The choice of location would have been influenced by a number of factors, for example the stratigraphy of the Nanny Town site previously mentioned suggests that it was located on a more ancient native settlement, with the post-Indian phases dated by the presence of Spanish pieces of eight in the relevant contexts (Funari 2010, 348).

One recurring feature of these excavations is on the level of material culture, the level of everyday practice. The Palmares excavation yielded an assemblage largely made up of ceramics. These included coarse earthenware of different varieties, similar to the wares used by the Dutch and Portuguese (Funari 2010, 364). The fact that these European-style artefacts were coarse is significant, indicating that they were utilitarian and therefore that their presence can be attributed to exchange with non-elite colonists.

As such, a class component must be factored into the Maroon/coloniser relations. Furthermore, a very large amount of Aratu ware was discovered as well as some similar to the Tupinamba red slipped ware of local native Brazilians (Funari 2010). The relation is made more complex by the fact that the Tupinamba ware was adapted to be similar to the Ovimbundu African pottery, ‘probably indicating a convergence of African and native traditions’ of a type that has not been identified elsewhere (Funari 2010).

This example suggests a remaking of culture at Palmares; a more hybrid form of living where perhaps the conjunctures of history (class differences amongst the Europeans, contingent groupings with local ‘natives’) helped form a new workable knowledge and a flourishing of social (not just military) activity. In fact, these Creole manifestations are also evident at other sites (see Agorsah 2010, 333; Funari 2010, 370).

Conclusions

The discourse on slavery often seems to ignore the idea of a slave voice, even one only approximated at through layers of dirt and representation. Trouillot (1995) provided a thorough analysis of both the Haitian Revolution and how it has been silenced by intellectuals and imperialists alike. But the revolution was not merely an Event, a counterpoint to the depoliticised non-event. It was born of a long history of resistance and survival.

Gerard Vizenor brings these terms together to create his notion of survivance: a survival that is also resistance, based on an idea of succession and a flourishing vision of sovereignty even in the face of extreme violence or oppression (Kroeber 2008, 25). The point of this is not to overplay some notion of squeezing the best out of the worst situations. Vizenor is writing of new hybrid forms of organisation made by the hammer of colonialism against the anvil of colonised communities. I feel that the practice-focused approaches to archaeology can be useful here, emphasising the essential mobility of the processes of production and ideology.

Theoretically, in the way of Spivak (1988), Django cannot speak. The enormous condescension of posterity is part and parcel of a hierarchical academic discourse, and is written into the fabric of the international law (Mieville 2005, 236) which even today traps Haiti in poverty. But it is always possible to improve the histories of the subaltern, to make them more holistic and less one-dimensional, and the material focus of archaeology is most appropriate to this.

I found Django Unchained exhilarating. I also think it is interesting to think of the production as an intervention. In some ways the film was more truthful than the most intense documentaries, the artistic license allowing the makers to go outside the strictures of the Just So story and play about with the idea that a black slave might actually have done something extraordinary. We saw a vision of freedom, perhaps not the most realistic vision but certainly one that went beyond the norm of the slave merely observing their lot in life. What is the appropriate way to represent slavery? It must surely be one that does this in some way, which attempts to do justice both to the horrors of history and to the humanity of those oppressed.

Bibliography

- Agorsah, K. (2010) ‘Scars of Brutality: Archaeology of the Maroons in the Caribbean’, in A. Ogundiran and T. Falola (eds.) Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African diaspora. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 332-354

- Allen, D. (2004) Talking to strangers: anxieties of citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education. Chicago: Chicago University Press

- Beaudry, M. (1990) ‘Review: The Recovery of Meaning’. Historical Archaeology. 24 (3). 115-118

- Funari, P. (2010) ‘The Archaeological Study of the African Diaspora in Brazil’, in A. Ogundiran and T. Falola (eds.) Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African diaspora. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 355-371

- Guyatt, N. (2009) ‘‘‘The outskirts of our happiness”: Race and the lure of colonization in the Early Republic’. The Journal of American History. 95 (4). 986-1011

- Kroeber, K. (2008) ‘Why it’s a good thing Gerard Vizenor is not an Indian’, in G. Vizenor (ed.) Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. 25-38

- Leone, M. (1984) ‘Interpreting ideology in historical archaeology: using the rules of perspective in the William Paca Garden in Annapolis, Maryland’, in D. Miller and C. Tilley (eds.) Ideology, power and prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 25-35

- Mieville, C. (2005) Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law. Leiden: Brill

- Norton, H. (2007) ‘The challenge in locating Maroon refuge sites at Maroon Ridge, St. Croix’. Journal of Caribbean Archaeology. 7. 1-17

- Orser, C. (1994) ‘Toward a Global Historical Archaeology: An Example from Brazil’. Historical Archaeology. 28 (1). 5-22

- Spivak, G. (1988) ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, in C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (eds.). Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. 271-313

- Stahl, A. (2008) ‘Colonial entanglements and the practices of taste: an alternative to logocentric approaches’. American Anthropologist. 104 (3). 827-845

- Trigger, B. (1984) ‘Alternative Archaeologies: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist’. Man. 19 (3). 355-370

- Trouillot, M. (1995) Silencing the past: power and the production of history. Boston: Beacon Press