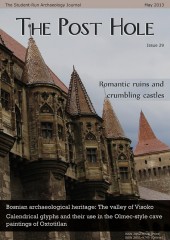

I have always had a great love of the Romantic Movement in late-eighteenth century literature. With its predictable but stirring plot motifs of fleeing virgins and avaricious, wanton patriarchs, crumbling castles and secretive ruins with many a subterranean tunnel that lead to who knows where, and the mellifluous nature of the writing itself, like a stream of panoramic landscape description in an age before cinematic camera angles, all build up to make a school of writing known as the Gothic. There were, however, facets of this vital part of the canon of literature that I had not previously considered; its impact upon antiquarian studies into medieval architecture for one, and the impact these studies had upon it for another.

Without trying to draw too complicated a picture, we might imagine the social milieu of the late-eighteenth century as a cooking pot. Into this we add the growing interest in British medieval history and its concomitant architecture, an aesthetic appreciation for natural and man-made landscapes divided into the picturesque and the sublime, the resurgence of the antiquarian order, and the growing availability of books to the new middling social class. In this pot it stands to reason that each ‘ingredient’ would have an impact on the other, moulding it and changing it accordingly, and that it, in turn, would experience transformations as it came into contact with other ‘ingredients’.

If this metaphor is not too far-fetched, the theory that the contemporary antiquarian study of medieval ruins and castles – with its engravings of man-made structures crumbling into nature, giving rise to feelings of melancholy awe and a wondrous rapture for the heritage of these buildings, its fixation on the secretive and neglected form of ruins, and the defensive attributes of castles against the dangerous and dramatic landscape of the medieval period – shared much with the fiction of the day seems more than reasonable. Similarly, the fact that ruins and castles feature in so many Gothic romances, from Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto and Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho, to Walter Scott’s Kenilworth and Edgar Allan Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher, makes the mutual influence of these factors undeniable.

It might seem a bit of a stretch to consider this link, yet the evidence is clear and, unfortunately, has been neglected in scholarly research. The use of contemporary fiction is a part of this research that forms a new and interesting debate on the veracity of certain written sources. While historical texts are taken explicitly as the truth, literature is not even considered, despite the fact that it reveals so many cultural themes from the time in which it was written.

Ann Radcliffe’s novels are set in Europe during a time in which many middle-class intellectuals travelled abroad for the Grand Tour; she sets her characters in ruins and castles from the medieval period just as antiquarians are beginning to study these structures in earnest; and her use of victimised women in her books speaks of the new political freedoms for women in Britain at the time. These are not coincidences; they are the considered implementation of social themes into a palatable and popular format, and academics ought to consider fiction as such.

It is not only fiction that has experienced the avoidance of archaeologists, but also the eighteenth century as the birth of the discipline. Many consider the scientific, systematic school that emerged in the nineteenth century to be the beginning of archaeology as we know it, but the links between modern scholarship and antiquarian pursuits in the eighteenth century would prove otherwise.

Studies of castles from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, though clearly different in approach, are equally fixated upon the defensive attributes of these structures, implying the danger of the period and thereby establishing a link not only to eighteenth century scholarship, but also to fiction. Similarly, the modern appraisal of ruins as picturesque scenes of an unknown past has gone unchanged since this early time of Romantic appreciation.

This research is ambitious in its scope, yet it amounts to a reconsideration of the discipline of buildings archaeology in light of new approaches and new considerations. The eighteenth century cannot be written off as a time of little or no influence merely because it was a time of Romanticised views; and the use of contemporary fiction as a useful tool for cultural study ought to be taken up by historical archaeologists seeking the views and beliefs of the people who inhabited the past.

It is vitally important to take a chance on original, unique views, for in doing this we can challenge the accepted history of all of us, and make scholarship what it was always meant to be – subject to debate and opinion, and reinforced by evidence that is there to be considered, not ignored.