Although insect-like animal figures form only a minor part of Olmec-style art, their significance to the Formative period inhabitants of the southern Gulf Coast lowlands, should not be underestimated. In this paper, I analyze all documented examples of insect-like forms in Olmec-style art, and detail their possible meaning in light of both contextual data and Mesoamerican analogs from the Classic and Late Post-classic periods. It is found that insectiforms may have symbolized transcendence or movement relative to an axis mundi.

Introduction

“Insectiforms”, a general term encompassing artistic representations of all types of terrestrial arthropods such as insects and arachnids, are not a common subject in Olmec-style art. Unlike felines (Coe 1972; Grove 1972; Joralemon 2007), crocodilians (Stocker, Meltzoff, and Armsey 1980), frogs and toads (Kennedy 1982), serpents (Otero 1975), and even sharks (Arnold 2005); insectiforms are found on only two known examples of Olmec-style art and writing. These representations are limited to the southern Gulf Coast lowlands of Mexico, in the area surrounding the major ceremonial centre of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. Although their restricted distribution and low frequency might lead to the assumption that insectiforms were not prominent features in the religious and political symbolic systems for which Olmec-style art is most well-known, these representations occur in contexts which suggest that insectiforms were potent symbols to the inhabitants of the southern Gulf Coast of Mexico during the Early Formative period (1200-900 BC).

In this paper, I attempt to clarify the significance of insectiforms in Olmec-style art and writing. To accomplish this task, I analyze all documented examples of insect-like forms in Olmec-style art and detail their possible meaning in light of both contextual data and Mesoamerican analogs from the Classic and Late Post-classic periods. This evidence suggests that insectiforms may have served as symbols of transcendence or movement in reference to an axis mundi in both Olmec-style art and writing.

As mentioned previously, the only two known examples of Olmec-style art with representations of insectiforms – San Lorenzo Monument 43 and the Cascajal Block – are from the southern Gulf Coast lowlands in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Both of these artifacts can be assigned to the late Early Formative period. San Lorenzo Monument 43 was discovered in the context of San Lorenzo B phase fill dated to approximately 900 BC (Coe and Diehl 1980, 352). The Cascajal Block was reportedly found in a gravel quarry near the community of Lomas de Tacamichapa. A majority of the ceramic sherds and clay figurine fragments from the same area also date to the San Lorenzo phase (1200-900 BC) (Rodríguez Martínez et al. 2006, 1611).

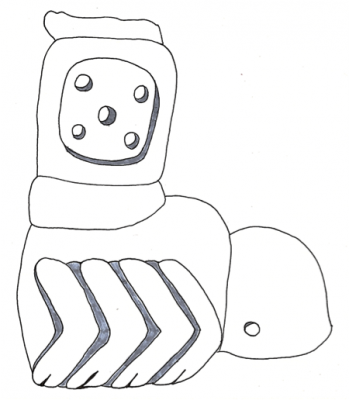

San Lorenzo Monument 43 (Figure 1) is a small three-dimensional basalt sculpture which measures 38cm in height, 36cm in length, and 24cm in thickness. It depicts an insectiform with a jointed body, consisting of a head, thorax, and abdomen, although several smaller segments adhere to the abdominal section, possibly forming a tail. Unfortunately, this portion of the figure also appears to have been damaged. More reminiscent of an arachnid, such as a scorpion, than an insect (see Cyphers 2004, 104-105; Medellín Zenil 1971, 42), the figure has eight segmented legs depicted in high relief descending from its thorax. The head is slightly pointed and has two eyes rendered as punctate circles towards the bottom of each side of the head.

Most notably, the abdominal section of San Lorenzo Monument 43 also contains a circular low-relief panel with five punctate circles organized into a quincunx design -- a common geometric symbol in Mesoamerican iconography consisting of five points arranged in a cruciform pattern, such that four of these points form a square and a fifth serves as its center (MacLeod and Stross 1990, 17, Fig. 1; Séjourné 1970, 90-91; Stross 1986, 283; Taube 2004, 76).

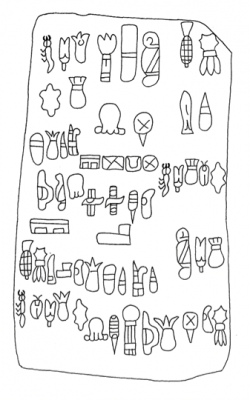

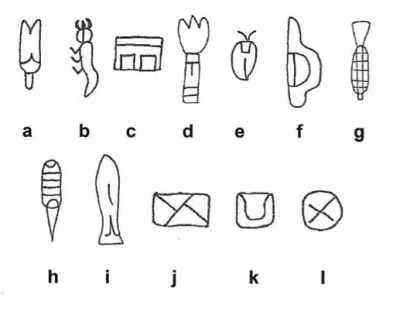

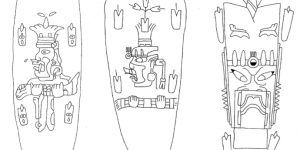

The Cascajal Block (Figure 2) is a serpentine slab measuring 36cm in length and 21cm in width. It is 13cm in thickness. The block is incised with 62 graphic signs (possibly glyphs). These signs make up a signary of 28 abstract and naturalistic designs (Rodríguez Martínez et al. 2006, 1612-1613). The abstract signs are common in Olmec-style iconography (Joralemon 1971) and include the crossed-band (Figure 3l) and the U-shaped sign (Figure 3k). Among the naturalistic signs, there are some which resemble plants such as corn (Figure 3g); others appear to be objects common in the iconography of Olmec-style art in the Gulf.

Among the possible animal forms depicted on the Cascajal Block, the most relevant to this study is Sign #4 (Figure 3b). This graphic sign occurs three times in the Cascajal Block and depicts an insectiform rendered in profile. These figures are reminiscent of San Lorenzo Monument 43, but are shown two-dimensionally with only three jointed legs, suggesting that they are not arachnids. Furthermore, the heads of each of these figures are bisected and decorated with mandibles. The bodies of these figures share the same general undulating form which is sometimes segmented, but not always.

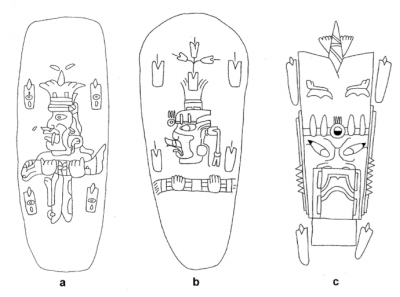

Although there has been some argument concerning the orientation and reading order of the signs on the block (compare Rodríguez Martínez et al. 2006; Magni 2008; and Mora-Marín 2009), their relationship to Olmec iconography of the Early and Middle Formative periods is clear. The general meaning of its incised signs however, remains elusive. To address at least part of this problem, i.e., the meaning of the insectiform in Sign #4, I would first like to draw attention to its placement in a repeated sequence in involving Sign #1 – a maize sprout design marked by a V-shaped cleft (Figure 3a). In another sequence, Sign #15 (Figure 3e), is situated between Signs #1 and #4. It is interesting to note that in other examples of Olmec-style art, such as a series of jade celts from nearby Río Pesquero (Figure 4), Sign #1 is often used to symbolize sprouting maize, and is frequently affiliated with representations of an axis mundi through the symbolism of the quincunx. This identification, in turn, suggests that the insectiform in Sign #4 is also related to Formative period conceptions of an axis mundi. Confirmation of this symbolic relationship exists in other examples of Olmec-style art, notably San Lorenzo Monument 43.

Insectiforms in the Mythologies of Mesoamerica

Like many societies around the world, the peoples of Mesoamerica did not classify insectiforms in a manner congruent with the Linnaean taxonomic system of Western science and entomology (Sutton 1995, 254-255). Rather, mythological narratives appear to have been the most salient sources for the conceptualization and classification of terrestrial arthropods (see Berlo 1983; Curran 1937; Kelley 1972; Taube 1983, 2003). Central among these myths were references to the axis mundi (Signaos 1985, 129-130).

For example, the Late Post-classic and Early Colonial period Mexica sources collected by the Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún, frequently mention insectiforms. In many of these sources, spiders, scorpions, and ants were depicted not only as poisonous adversaries, but their natural habitat of bushes and trees was also noted (Curran 1937, 196-197; 200-203).

The predatory nature of scorpions is also well documented in the painted manuscripts of the Post-classic Maya, such as the Madrid Codex (Tozzer and Allen 1910, 305-306). Thus, even though references connecting insectiforms to an axis mundi no longer appear salient by AD 1500, these ethnohistoric sources suggest that indigenous observations of the natural ecology of these insectiforms may have informed some of the symbolism present in the Olmec-style art of the Formative period. Indeed, such connections are much clearer in the Middle Classic period (AD 450-650) art of Teotihuacán.

Recalling the linguistic associations between spiders and mothers among contemporary Nahuatl, Otomi, and Huichol speakers (Kelley 1972), spiders also appear to have formed a significant part of Classic period religious and political symbolism. Karl Taube (1983), for instance, has analyzed the depictions of the so-called “Spider Woman” of Teotihuacán. In addition to her distinctive “fanged” nosebar suggesting the pedipalps of a spider, Taube has found that the Spider Woman had a number of iconographic associations including the “ollin” or intertwined tree in the murals of Tepantitla (Taube 1983, 151, Fig. 1) and quincunx signs in the murals of Tetitla (Taube 1983, 153, Fig. 3). Interestingly, the architectonic forms of this deity were also associated with agricultural bounty at Teotihuacán (Taube 1983, 152, Fig. 2). Thus, it appears that the Spider Woman was most closely related to the earth and underworld, water and creation and served to mediate and transverse these realms of the cosmos (Taube 1983, 140-143). Interestingly, a different insectiform, the centipede, appears to have served as a similar conduit between the underworld and the heavens among the Classic period Maya, although in this role centipedes seem to have been contrasted with serpents (Taube 2003, 437-438). While centipedes were primarily associated with death and the underworld, serpents were more commonly connected with bringing water from the underworld into the sky realm.

Taken together, these ethnohistoric and archaeological analogues further serve to highlight the relationship between various insectiforms and the concept of the axis mundi. However, they also point to the transcending aspects of insect-like figures relative to the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the cosmos. Not only are insects and arachnids masters of the land and trees, they are also capable of moving from the underworld to the celestial realm through these arboreal axes mundi (Siganos 1985, 130-133). It is therefore not surprising that insectiforms were simultaneously seen as harbingers of life and death, creation and destruction in ancient Mesoamerica. They transcended traditional categorizations of the world.

Conclusions

This paper has argued that the insectiforms present in Olmec-style art and writing are best interpreted as symbols of movement or transcendence relative to an axis mundi. Archaeological and contextual evidence has shown that these insect-like forms were related to maize agriculture, maize sprouts, and the axis mundi during the Formative period. An examination of Mexica ethnohistoric sources from the Late Post-classic and Early Colonial periods and Classic period archaeological materials from Teotihuacán, suggested that even though insectiforms such as ants and spiders took on new meanings during the ensuing millennia, they also maintained a symbolic relationship with the concept of the axis mundi which emphasized their ability to transcend many of the salient of conceptual categories (i.e., life and death / creation and destruction / the underworld and the celestial realm) of ancient Mesoamericans. Given the continuity of symbols such as the quincunx and the axis mundi affiliated with the insectiforms, it is very likely that similar notions informed the use of these figures in the Olmec-style art and writing of the Gulf Coast lowlands of the late Early Formative period (c. 900 BC).

Bibliography

- Arnold, P.J. (2005) The Shark-Monster in Olmec Iconography. Mesoamerican Voices 2: 5-36.

- Berlo, J.C. (1983) ‘Warrior and the Butterfly: Central Mexican Ideologies of Sacred Warfare and Teotihuacan Iconography’ in Berlo, J.C. (ed.) Text and Image in Pre-•Columbian Art: Essays on the Interrelationship of the Verbal and Visual Arts. 79-118. International Series, No. 180. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Coe, M.D. (1972) ‘Olmec Jaguars and Olmec Kings’ in Benson, E.P. (ed.): The Cult of the Feline. 1-18. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Coe, M.D., and Diehl, R.A. (1980) In the Land of the Olmec. Volume I. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Curran, C. H. (1937) Insect Lore of the Aztecs. Natural History 39:196-203.

- Cyphers G., A. (2004) Escultura Olmeca de San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. Mexico D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico.

- Grove, D.C. (1972) ‘Olmec Felines in Highland Central Mexico’ in Benson, E.P. (ed.): The Cult of the Feline. 153-164. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Joralemon, P.D. (1971) A Study of Olmec Iconography. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology No. 7. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

- Joralemon, P.D. (1976) ‘Olmec Dragon: A Study in Pre-Columbian Iconography’ in Nicholson, H.B. (ed.): Origins of Religious Art and Iconography in Preclassic Mesoamerica. 27-71. Latin American Studies Series, No. 31. Los Angeles: University of California /Latin American Center.

- Joralemon, P.D. (2007) Jaguars, Shamans and Rulers in Olmec Art. Arts & Cultures 8: 133-145.

- Kelley, G.P. (1972) Linguistic Observations for the Spider Concept in Mesoamerica. Katunob 8 (1):31-33.

- Kennedy, A.B. (1982) Ecce Bufo: The Toad in Nature and in Olmec Iconography. Current Anthropology 23 (3): 273-290.

- MacLeod, B., and Stross, B. (1990) The Wing-Quincunx. Journal of Mayan Linguistics 7: 14-32.

- Magni, C. (2008) Olmec Writing. The Cascajal Block: New Perspectives. Arts & Cultures 9: 64-81.

- Medellín Zenil, A. (1971) Monolitos Olmecas y otros en el Museo de la Universidad de Veracruz. Corpus Antiquitatum Americanensium, Volume 5. Mexico D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

- Mora-Marín, D.F. (2009) Early Olmec Writing: Reading Format and Reading Order. Latin American Antiquity 20 (3): 395-412.

- Otero, L. (1975) The Serpent as an Element in Olmec Iconography. Revista Mesoamericana 2 (1): 5-20.

- Reilly, F.K., III (1995) ‘Art, Ritual, and Rulership in the Olmec World’ in The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. 27-46. Princeton: The Art Museum, Princeton University, Princeton.

- Rodríguez Martínez, Ma. del C.; Ortíz Ceballos, P., Coe, M.D., Diehl, R.A., Houston, S.D., Taube, K.A., and Delgado Calderón, A. (2006) Oldest Writing in the New World. Science 313 (5793): 1610–1614.

- Séjourné, L. (1978) Burning Water: Thought and Religion in Ancient Mexico. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Siganos, A. (1985) Les Mythologies de l’Insecte: Histoire d’une Fascination. Paris: Librairie des Méridiens.

- Stocker, T.L., Meltzoff, S., and Armsey, S. (1980) Crocodilians and Olmecs: Further Interpretations in Formative Period Iconography. American Antiquity 45 (4): 740-758.

- Stross, B. (1986) Some Observations on T585 (Quincunx) of the Maya Script. Anthropological Linguistics 28 (3): 283-311.

- Sutton, M.Q. (1995) Archaeological Aspects of Insect Use. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 2 (3): 253-298.

- Taube, K.A. (1983) Teotihuacan Spider Woman. Journal of Latin American Lore 9 (2):107-189.

- Taube, K.A. (2003) ‘Maws of Heaven and Hell: The Symbolism of the Centipede and Serpent in Classic Maya Religion’ in Ciudad Ruiz, A., Humberto Ruz, M., and •Josefa Iglesias Ponce de León , Ma. (eds.): Antropología de la Eternidad: La muerte en la cultura Maya. 405-442. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas.

- Taube, K.A. (2004) Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Tozzer, A.M., and Allen, G.M. (1910) Animal Figures in the Maya Codices. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. Volume IV, Number 3. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University.