Last year, as an archaeology undergraduate at the University of York, I was fortunate enough to give a presentation at the first ever ASA Conference, held within my department. I had just completed my dissertation and had given my final assessed lecture on the same subject (Wajdner 2013). The conference was a great opportunity to articulate my research in a more open and informal manner, but it also afforded a great platform for sharing my ideas directly to my contemporaries in the wider field. Today, as I once again begin that journey of thesis research for my postgraduate degree, I am buoyed by the prospect of the next ASA conference. My research this year will continue themes from the last, and will also aim to provide insight into larger theoretical ideas, which I feel are important to be understood via student conferences and journals. I strongly feel that there is something very special with this platform of dissemination, to be able to speak openly and frankly about research with others who are at the starting point, like myself, in their careers. Excited not only as all budding academics are when talking about intellectual matters close to their hearts, but also because I feel it can often give insight in an accessible, unrefined academic language to others grappling with big ideas and issues. This is why I have reproduced my presentation from last year to both re-engage the tone of discussion for my own research, and to hopefully prepare the ground for this debate prior to this year’s conference.

In my undergraduate thesis, I was interested in the theory transfer within the heritage sector in England, with the aims of examining the effectiveness of the bridge between the two and to assess whether its construct is effective or lacking. Throughout my research, I came to the observation that the current bridge within the heritage management framework in England is unable to act effectively according to modern critical perspectives of cultural heritage, and that to remain relevant to society, these shortcomings must be addressed and acted upon at all levels to provide meaningful future frameworks for cultural heritage. I realise that this is, in reality, nothing revolutionary. However, I do feel it is important, especially for those of us entering the heritage sector who will soon be tacking these very real issues head on. So I hope to simply equip us with this knowledge in advance.

But first let’s consider some definitions of what I will be talking about. The Faro Convention defines cultural heritage as follows: ‘a group of resources inherited from the past which people identify, independently of ownership, as a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions’ (Council for Europe 2005) (Fig 1). We might think that this is reasonably simple, and possibly universally acceptable, and in one sense that is correct. Those interested in the critical study of heritage matters would agree with this definition, and be motivated by the idea that people have a right to participate in cultural life. This continues in that they believe every single person should have a meaningful way of expressing that; expressing it for, and in, society. In addition, they would argue that people’s value should be at the centre. This definition of cultural heritage is quite broad, and potentially very useful, but it is also a little idealist. Enter then, the other side of heritage discussion: those more involved and concerned with the practice of heritage. Whilst they would arguably like to have this definition, ultimately it is quite detached from the real complexities faced in their professional role.

I argue then that there is a problem. There is, and always has been, a problem with definition for those in theory and those in practice to agree what cultural heritage is. However, I would like to take this a step further and say there is a problem with the current construct of heritage management in the UK. And, of course, if there is a problem, there needs to be a solution. If there is to be a solution, this requires people, and we are the people (those of us setting off on our careers into the heritage sector). Therefore this problem requires our attention.

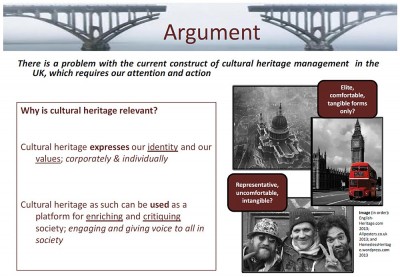

But, why is this important? Cultural heritage is relevant because it expresses our identity and our values (Fig 2). However, what if we are only seeing the forms which are elite – the celebrated, higher-end of heritage; the dictated, authorised forms of heritage? If this is the case, then this would not provide a very reflective demonstration of cultural heritage. Often we receive the idea that cultural heritage in the UK – what is perceived by practice – is the comfortable form of heritage, the corporate form which seems commonsensical. What about other forms of heritage; perhaps the more humble expressions of value and identity? I subscribe to the school of thought that heritage is a process, and its ‘management’ should be the directing of people to connect with their heritage, rather than merely being concerned with heritage as product (Smith 2006, 44-45). Our mission as professionals then should be to promote these meaningful connections; helping communities to understand themselves and listening to how they identify and what they value, regardless of where this takes us, which is why it is often an uncomfortable understanding of what cultural heritage is.

Now we must move on to the consideration of theory transfer. At an international level, there are organisations like the Council for Europe and UNESCO which are quite detached from the practical management of heritage. It is quite easy to see the transfer between theory and practice at this level, but what about at a national level? Things are more selective here as, for example, the UK government does not have to sign up to their charters – as is the case currently with the Faro Convention. They can disregard these if they find the proposed definition does not fit with their own perceptions of what heritage is, or methods for the management of cultural heritage. Immediately, a possible blockade for theory transfer can be recognised; it is very dependent on the existing policy framework. Because of this, at a local level there are problems, as the definition of cultural heritage for local practitioners is predominantly dictated by the government.

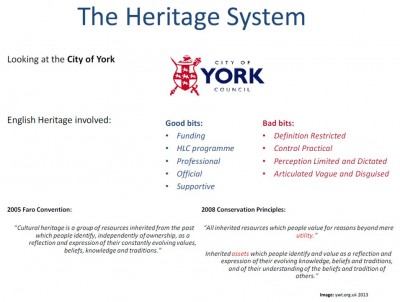

Local councils and communities utilise English Heritage frameworks. English Heritage helps councils such as at the City of York, deal with their cultural heritage which has many advantages. For example, they help to assist in conservation, funding, and professional support for York practitioners dealing with the many cultural heritage assets used within the city and its tourist industry. There is also the ‘Historical Landscape Characterisation’ programme, working to pinpoint significances and understanding of heritage values, and compiling these onto a GIS system showing various types of heritage, what it is, how it relates to others, and in what way it is important. This is important and useful, however it is interesting that the interpretation of heritage definition in this regard is slightly skewed. This is seen clearly when comparing the Faro definition of cultural heritage up against the English Heritage definition, in which two vital differences include: mere utility and heritage assets (English Heritage 2013a; English Heritage 2013b) (Fig 3). These terms invoke the idea of physical forms of heritage only; distinct, subtle differences whereby in order for heritage to be engaged with within the English Heritage framework of management, it must be something tangible, something that can be physically protected. As a result, any other form of intangible cultural heritage is essentially ignored as it cannot be officially acknowledged given the remit of English Heritage as practical protector. In reality, this makes complete sense as, given the above remit, heritage must be in some way controllable in order to be protectable.

It is not all good though as, due to the above, the definition is restricted. Perception of cultural heritage is given through the definition and therefore the form that the authorised heritage framework recognises. An example from York can be seen when considering the views of the city. In York, there are some amazing views. Whilst these views themselves are worth protecting, they are intangible. Their values cannot be expressed within the authorised discourse, so groups like the York Civic Trust, who have an interest in protecting these aspects of York, have to engage with debate revolving around the heritage management framework. Unfortunately, as promoters of something outside of the authorised definition, they must borrow terminology, ultimately compromising their message for protection due to the fundamental need to penetrate this authorised discourse, resulting in them masking their argument (Wajdner 2013a, 25-27). This leaves communities at grass root level floundering a little bit, as they are largely unsupported due to this language barrier.

I hope you will agree that there is a problem. This problem exists with English Heritage. The problem lies at a deep rooted, philosophical level of what English Heritage is for, i.e. to protect controllable, physical objects. It cannot deal with more fluid, conceptual ideas of what cultural heritage could be. It has to be a controlling framework, but this is at odds with the theoretical call for cultural heritage to be a democratic process of understanding, where everyone should have equal voices. If there must be a management framework, there cannot be complete freedom to express multiple forms.

I’ve brought you then to the point where traditionally the solution is suggested. Unfortunately, there isn’t really one to offer. But to be honest, this isn’t the take away message I want to share. The main point I hope to get across is the need to recognise this problem. I hope that, if anything, we take away the knowledge that, as we enter the heritage sector in our careers, there is an issue deeper than just difference of nature between theory and practice. We need to shift the intellectual landscape; this is the only way we are going to be able to provide a long-term solution. So let’s go through some options.

When a bridge doesn’t work, what do we do? We could dismantle it. However, the current bridge in place, English Heritage, does do something quite well – the protection of tangible cultural heritage. If we dismantle it completely, we end up throwing the baby out with the bathwater. But we have to do something as there are clear issues. What should we do?

There is an evolutionary change happening right now within the heritage sector, and this is something we can get on board with. However, just as it takes a great distance for a large, heavy laden ship to change direction, so too does it take time for the intellectual landscape to see significant change. In the very first instance for many of us, there are cultural heritage management training programmes: masters, general archaeology degrees, etc. We could be engaging with schools and local communities. Just getting involved and spreading this understanding and drive for new models of heritage awareness is vital. We need to be equipping ourselves with the correct tools, which is why this argument itself fits into raising awareness in the long term. In the short term, there is the need for academics to be employed by places such as English Heritage. An example of this is seen by Dr. Joe Flatman from UCL who was appointed to a position within English Heritage in 2012. This is a significant step as he has a wide range of research interests, but more importantly, a critical understanding of modern perspectives of theory.

So where have I led you? I’ve concluded that there is a problem with the system; it’s complicated, but it is worth us knowing at this stage in our careers that it is there and we need to appreciate that it is deeply rooted. Also, very importantly, we must have a cultural heritage that is effective. We cannot just sit hoping that someone comes around and makes a difference. Cultural heritage is our method of expression, but not everyone has the same opportunity to get involved and express themselves with this megaphone to the political arena. A useful way to think about it is like this: the political system works to represent us, but it is not on an individualistic basis. It is instead through community identities and ways in which we are represented in society. So it is okay for most of us, as we have a clear identity which can be heard and understood. But what about periphery groups such as homeless communities? They don’t have access to that voice. So we need to have cultural heritage that is relevant, effective and really connected.*

What can we do then? We have to firstly recognise this issue. We can also further educate ourselves, getting on board to equip ourselves with the tools necessary to be effective in our careers. It is not all doom and gloom, and I have not meant to discredit English Heritage because, in reality, they are doing a great job. There is set up within English Heritage, the ‘Heritage Intelligence Team’, which works quietly in the background, often snubbed by perhaps the old school heritage professionals in the wider sector, as they actively seek to move this debate forward. A part of their role is to develop links between heritage organisations and research groups, and they are truly doing a fantastic job. They are essentially sharing intelligence and influencing policy, a clear sign that change is happening at all levels.

Finally, I would like to make an additional suggestion. I myself have benefited greatly by having two incredibly strong mentors. These are individuals who play important roles, one as a key scholar within the theoretical and academic sphere, and the other who is a key player in the practice of heritage. Both have given me great insight, which leads me to advise that, as you seek to grow and be effective in your own career as the next generation of heritage professionals, do try and gain supervisors or mentors on either side of this bridge to guide and direct your learning, giving a vital dual perspective on real world issues.

(*I recommend reading about Rachel Kiddey’s work with homeless communities, demonstrating the powerful tool that archaeology can be in giving voice to periphery groups, and how their cultural heritage can inform and direct understanding across community groups: http://homelessheritage.wordpress.com)

Bibliography

- Council of Europe (2005) Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, CETS No.: 199.

- English Heritage (2013a) Definition: Heritage [Online] English Heritage, UK. Available at:

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/professional/advice/hpg/hpr-definitio... [Accessed on 18 March 2013]. - English Heritage (2013b) Definition: Cultural Heritage [Online] English Heritage, UK. Available at: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/professional/advice/hpg/hpr-definitio... [Accessed on 18 March 2013].

- English Heritage (2010) Draft Statement of Ambition: Historic Environment Objectives for the City of York. York: English Heritage.

- English Heritage (2008) Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidelines. Swindon: English Heritage.

- Smith, L. and Waterton, E. (2012) ‘Constrained by Commonsense: the authorised heritage discourse in contemporary debates’ in R Skeates, C McDavid and J Carman (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology, 153 – 171. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, L. (2006) Uses of Heritage. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Wajdner, B. (2013a) Cultural Heritage Theory and Practice: illustrating real world complexities using the City of York as a case study [Online] Academic.edu profile. Available at: http://www.academia.edu/4899946/Cultural_Heritage_Theory_and_Practice_il... [Accessed 21st February 2014].

- Wajdner, B (2013b) cultural Heritage Theory and Practice: raising awareness to a problem facing our generation – ASA1 Conference Presentation [Online] Academia Profile. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/6213430/Cultural_Heritage_Theory_and_Practice_r... [Access 26th February 2014].