Amy works as a small finds specialist working for the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS). She specialises in metal artefacts. It is her role to liaise with the public, especially metal detectorists, identify their finds, and record them onto the online PAS database (available at www.finds.org.uk). The database will soon have 1 million objects recorded!

How did you get involved in your current role?

I studied archaeology at the University of York, and at the same time, I worked as a demonstrating archaeologist at ARC (now Jorvik DIG) and at St Leonards Archaeology Live excavations as a Finds Assistant for York Archaeological Trust, and as front of house at York Museums Trust. This gave me a good background in explaining archaeology to the public. It also allowed me to apply as an internal candidate for a job at the Yorkshire Museum, digitising the Jim Halliday Archive, a huge collection of record sheets and digital images of metal-detected finds, so they could be integrated with the PAS database. This experience led to me being the only paid member of staff at Malton Museum for 6 months, where I recorded the actual finds from the Jim Halliday Archive. I also volunteered for the PAS in York, and with the Young Archaeologist’s Club. Now, with a good grounding in metal-detected finds, and experience of the PAS, I was able to apply for the Finds Liaison Officer job in South and West Yorkshire, and I was successful.

Working as a Finds Liaison Officer for the Portable Antiquities Scheme, could you explain what this scheme aims to do?

The PAS is a department of the British Museum. It aims to record the archaeological finds discovered by chance, by members of the public. We identify, describe and record the finds onto the PAS database.

What does this involve?

Most of the finds we record are discovered by metal detectorists, so we liaise closely with the local metal detecting clubs and provide out reach in museums to meet the independent detectorists. This involves a lot of evening work. There are nine clubs that I visit regularly. I also cover nine council districts in South and West Yorkshire, so I visit a lot of museums and run ‘Finds Afternoons’. These are drop-in sessions when people can bring in finds for me to examine. This is also the way I meet non-detectorist finders – people who might have spotted an artefact in a mole hill or in their garden, for example. Another part of the FLO role is helping with the statutory declaration of ‘Treasure’ objects under the 1996 Treasure Acts. We advise finders and help complete the declaration forms for the coroner, as well as identifying and writing reports on the finds. I occasionally have to give evidence in Treasure inquests, or organise an excavation of a particularly special discovery.

How does the PAS work to create links with the local community?

We try to outreach to groups in addition to metal detectorists, but after 15 years of increasing numbers of finds being recorded, we are now working at absolute capacity, and recording finds has to take priority over giving talks and manning stalls at local history fairs. That is a shame, as part of our role is to encourage greater public connection with archaeology, but we have only limited funding and no spare capacity at all.

What is the most exciting artefact you've found?

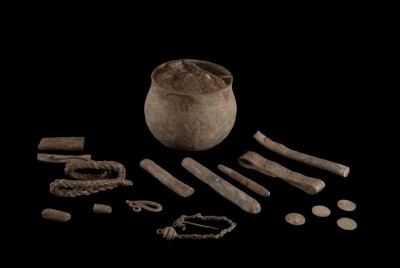

Not being a field archaeologist, I have never found any artefacts myself, except for spotting pottery lying on the surface of a field at a Deserted Medieval Village. (As it was a Scheduled Ancient Monument, I left it there untouched!). However, one great perk of my job is that I get to handle thousands of archaeological finds. Last week I recorded a Bronze Age socketed knife (database number SWYOR-CAF110), and this week a copper alloy beaded torc has been handed in. The most famous find I dealt with was probably the Vale of York Hoard (SWYOR-AECB53), which became known as the “most exciting Viking hoard discovered in the last 150 years”. It was my responsibility to deliver it safely to the British Museum, all £1,000,000 worth of it! However, the most exciting artefact was probably the Roman erotic knife handle (SWYOR-374234) which is very rare, and is particularly difficult to research on the internet!

As part of your role, you must have come into contact with some metal detector enthusiasts. What is your experience of them, and their affect on archaeology?

Metal detectorists get bad press, but the vast majority of the ones I meet are enthusiastic about archaeology, and responsible about the way they pursue their hobby. It’s worth remembering that most of their finds are from the topsoil, where objects are very much at risk of damage from farming. The finds are usually already out of context, and detectorists rescue them from further damage or destruction. The data being produced from recording detected finds does have the potential to change our understanding of archaeology. For example, the Roman coin data we are generating is amazing (our Finds Advisor Philippa Walton has recently published her PhD on this subject).

You have been involved with the ‘Castleford Youth Inclusion Project’, which provided after school sessions for children at risk from being excluded. How important do you think it is for children to engage with archaeology from a young age?

Children love archaeology and it is very good for them. It is a wonderful way to engage children who are not particularly interested in traditional subjects, and it provides a great way in to an amazing number of skills and topics. The abundance of transferable skills is one of the reasons I chose to study archaeology, and I wasn’t really expecting to get a job in the sector!

What qualifications do you have and where did you study?

I was home educated until I was 17, and then I went to sixth form college with just 2 GCSEs. I have A-levels in English Language, Psychology and Dance, and an AS in Archaeology. I then got my BA at York, and was lucky enough to find employment in archaeology straight away. Perhaps the most important qualification I gained early on, was passing my driving test – it’s a vital skill for a lot of archaeology jobs.

As a graduate of the University of York, what do you think was the most important skill you gained from your undergraduate degree that has helped in your career?

The degree gave me a good grounding in British Archaeology, as well as in techniques and theory, which has enabled me to develop my knowledge into my chosen specialism. However, I learnt a lot of the artefact-related skills I use in my work through my volunteering and paid work.

What projects are you currently working on?

My work is not project-based – it is a constant stream of artefacts to record, ‘Treasure’ cases to administer, enquiries to answer, and ‘Finds Afternoons’ or meetings to attend. I am currently training a new volunteer, and whenever I have time, there is data-cleansing work to be done on old database records.

Any tips for those interested in archaeology reading this interview who want to work in the same kind of role?

Practical experience is vital. We get hundreds of applicants for every paid role with PAS, no matter how short term it is, so if you do not already have experience working with finds and with the PAS database, you do not stand a good chance of being successful. It is also a role that only suits certain kinds of people. Although we work with lovely finds, we do not usually have time to do research – if you want to study artefacts, stay in academia. If you like record keeping, databasing, and being really organised, then PAS might be your natural home. Do as much volunteering as you can, and learn to drive!

For further information on Amy, visit: http://finds.org.uk/contacts/staff/profile/id/68

To access the PAS, follow: http://finds.org.uk/