The study of vernacular buildings has long since drawn the attention of academics, though best practice is a contention which continues to plague the discourse. While indebted to his heavily descriptive, functionalist antecedents, Matthew Johnson challenges the lack of explicit theoretical frameworks hitherto applied to the study of traditional architecture (see Gilchrist 2009). Johnson’s emphasis on human action and interaction sets the stage for an interpretation that moves beyond the purely functionalist, typological and economic paradigms used to read traditional buildings (Gerrard 2003, 173). He proposes that “material things are more important than simply tools for coping with the environment. Artefacts are social products…they are produced and have meanings assigned to them in a social milieu” (Johnson 1993a, 12). Johnson convincingly demonstrates that as these social meanings change, so too do the houses in which they are embedded. His explicitly termed ‘closure’ expresses the closing of the open-hall hearth area in Suffolk houses, and more subtly, the reciprocal structured and structuring nature it had on day-to-day communications. Johnson’s (1993a) contextual approach attempts a ‘case study’ in the post-processualist style advocated by Hodder (1986, 118–45), and has been heavily influenced by American vernacular discourse.

This essay seeks to evaluate Johnson’s theoretical approach, firstly, by focussing on the legacy of the ‘Great Rebuilding’ (Hoskins 1953, 44), and why Hoskins’ thesis still endures. In doing so, we may judge the extent to which it has influenced both current vernacular discourse, and Johnson’s subsequent work. Secondly, we will shed light on Matthew Johnson’s (1990, 245-259; 1993; 1997, 13-19; 2010, 1-20) theoretical approach to the study of traditional architecture. Simplistic economic explanations (Johnson 1990, 248-250) are rejected and proximal answers are sought in the changing social and cultural meanings of the ‘open’, ‘transitional’ and ‘closed’ houses of Western Suffolk. By appraising his structuralist intention we may be thrust into a position to assess whether his theory of ‘closure’ presents a profitable perspective on traditional architecture and the wider landscape (1996, 44-70). Finally, in looking to the work of Nat Alcock (1993) we may move beyond Johnson’s ideas, developing the approach to domestic architecture through changes to material possessions. Roberta Gilchrist (2012) achieves the same approach, though more theoretically informed than Alcock. By considering Alcock (1993) and Gilchrist’s (2012) work alongside Johnson’s (1993a), we may therefore assert both a highly important and persuasive approach to interpret vernacular architecture.

In 1953 W. G. Hoskins published “The Rebuilding of rural England, 1570-1640’. Hoskins used both archaeological and documentary evidence to argue for a substantial rebuilding of houses at a socially ‘middling’ level (King 2010, 54). Hoskin’s thesis, expressed in a typically flamboyant style, proposed that ‘between the accession of Elizabeth I and the outbreak of the Civil War, there occurred a revolution in the housing of a considerable part of the population…There was, first the physical rebuilding and substantial modernisation of medieval houses…and there was almost simultaneously a remarkable increase in household furnishings” (Hoskins 1953, 44). He focussed his attention to the rural landscape of Suffolk, where he believed this transformation was “inescapable” (Hoskins 1953, 34). Hoskins ascribed his building “revolution” (1953, 44) to the rising demand for privacy, and ultimately the economic influence of the Renaissance. He sought this economic impetus from “the bigger husbandmen, the yeomen and the lesser gentry” (Hoskins 1953, 50; Dyer 2006, 26), identifying the means for the “Great Rebuilding” (Johnson 1993b, 118), in the wider economic context, and the effect it had on population increase.

Despite criticisms (Alcock 1983; Ryan 2000, 20-1), Hoskins’ thesis (1953) became an orthodoxy in vernacular architectural studies. The “Great Rebuilding” was often used as an analogy for contemporary shifts in other spheres of social and economic history (Spufford 1984). The argument, however, was not assessed on a national, rigorously quantified basis until later reassessment by Robert Machin (1977, 33-40), and Chris Currie (1988). Hoskins acknowledges that his suggested population rise is an unprovable phenomenon, noting “the historian should not [ignore a convincing argument] because he sees little chance of proving his case statistically” (Hoskins 1953, 45, 46, 47 & 55; Johnson 1993a, 121). Despite more recent developments in this field, this attitude has survived in vernacular architecture discourse to the present day. Peter Smith’s ‘Houses of the Welsh Countryside’ (1988) was based on selective recording with no discussion of the biases this might involve. Additionally, Colum Giles in ‘Rural houses of West Yorkshire’ (1985, xix) uses the phrase ‘fairly random’ to describe his sampling methods. In any case, pointing these out is not to vilify Hoskins’ achievement, but rather emphasise the historical pervasiveness of his work. As a result, the ‘Great Rebuilding’ has remained one of the few broader concepts of historical significance of the ‘vernacular threshold’ (Johnson 1997, 17). A stronger reason for its acceptance was that it fitted the contemporary fashions in social and economic history, as well as Hoskins’ new ‘landscape history’ (Dyer 2006, 24). Hoskins himself identified the changing values of the Renaissance as the primary cause of the ‘Great Rebuilding’ (1953), though he failed to question the underlying reasons for the consequent rise in privacy (Johnson 2002, 176-183). According to Johnson the ‘Great Rebuilding’ was accepted on the grounds of its excellent coherence (Johnson 1993a, 121). However, it is often assumed that past cultural meanings are only accessible via documents, and that therefore the study of traditional buildings remains dry and technical; ‘the production of an inert form into which only texts can breathe life’ (Johnson 1993a, 124). In the words of Hoskins “the students of vernacular buildings…remain woefully ignorant of the documentary side of their field of study” (1967, 94). Behind the text and the artefact lie human thoughts, something that Hoskins fully appreciated.

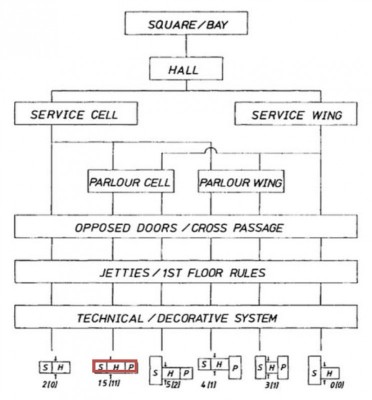

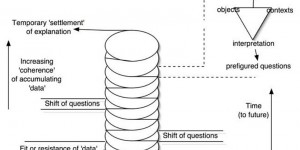

Johnson’s theory of closure emerged from this legacy, and the recognition that American vernacular discourse was, at that time, well ahead of its British counterpart. The “loss of innocence”, as Johnson termed it, in British vernacular discourse (1997, 13) was symptomatic of a lack of explicit historical interpretation (1997, 14). Johnson consequently turned to the structural and post-structural linguistics of Saussure (1983) and ultimately to historical archaeology arguing for a contextual approach to vernacular houses. For Johnson, the grammatical approaches put forward by Henry Glassie (1975), and James Deetz (1996), were important because they helped “make explicit the often implicit and unspoken process in the mind of the maker” (Johnson 1993a, 33). In this case, it models the way the final form of the building is thought out in implicit stages, a process referred to as a “competence” (Figure 2) (Johnson 1993a, 33). Johnson acknowledges that this was the first step towards understanding the meaning of an object, but criticised Glassie for failing to account for change over time (1993a, 181). This perceived shortcoming provided a practical outline for what Johnson contributed to the study of vernacular architecture. He proposed a grammatical approach of his own, based on the work of Chomsky (1965, 4) and influenced by Hodder (1986) to elucidate this ‘competence’ or ‘rules of composition’ that make up the ‘specialised body of practical knowledge’ behind western Suffolk’s timber framed houses (Johnson 1993a, 39). Johnson designated his competence the “craft tradition” (1993a, 38), and claimed that “in what follows only the most basic rules of layout will be given. The resolution will be less fine than that given by Glassie, but will cope with minor variations more easily” (1993a, 42). The grammar he subsequently offers provides a useful framework for investigating questions of meaning and subsequently employs this grammatical framework to the ‘open’, ‘transitional’ and ‘closed’ houses of Western Suffolk (Johnson 1993a, 44-89; 2010, 90).

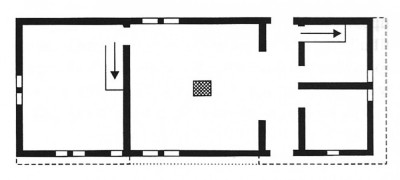

Open houses were characterised by a central hall consisting of two or more hierarchically arranged bays, which opened to the roof. According to Johnson, social intercourse within these late medieval houses was “governed by established rules of medieval patriarchy” (1993a, 55). He asserts that relationships between master, wife and servants were decidedly unequal, which is expressed through asymmetrical features, segregated functional spaces and proscribed patterns of circulation in the open house. The carefully composed interior of Bayleaf (Figure 1) demonstrates the asymmetrical segregation in three distinct bays.

The social meaning of the open hall is found at all levels of society (Mercer 1975, 22; Thompson 1995). The hall carried the meaning of a social structure that has been variously labelled, ‘Gemeinschaft’, or “peasant tradition” by Dobrolowski (1971, 277) and “patriarchal order” by Johnson (1993a, 54). It consisted of a structure based around the unit of the household (Gilchrist 2012, 114), and what Mertes calls (1988) “good governance and public rule” within which the members of the household were bound together by asymmetrical ties of kinship and dependence (Johnson 1993a, 54).

What followed, according to Johnson (1993a, 33) was a period of “renegotiation” resulting in a range from “extreme conservatism in their similarity to open-hall plans” to “early examples of the distinct form in the closed period” (Johnson 1993a, 64; Coleman 1979a; 1979b). Elaborate decorative details and unusual plans were typical (Alcock & Laithwaite 1973; Harris 1978, 67), and as a result Johnson labels these ‘transitional’ houses (1993a, 64). Consisting of the open house plan with the addition of an inserted chimney-stack, fully ceiled hall and lobby-entry (2010, 92), the multi-phased forms of ‘transitional’ houses vary from ‘conservative’ to ‘radical’ plans (1993a, 72; Walker 2003, 79-83).

Case Study: Lower Farm Risby

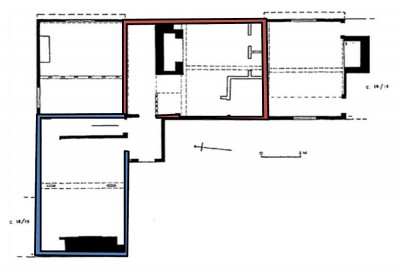

Lower Farm, though complex and originally of open-hall plan, illustrates the ‘transitional’ form, and shows as much variation in the way these changes were carried out as the newly built transitional houses themselves (Johnson 1993a, 64). The cross-wing was retained at Lower Farm, but the old hall was completely demolished and replaced with a fine new main range (Figure 2). The roof over the hall was rebuilt, but only a few blackened rafters survive. A parlour wing was added in the 16th century (Figure 3), with a jetty and gable to the north with stud-braces, three-window ranges and an external stack. Also at this point the service wing was remodelled, with a rail introduced into the cross-passage. The front was then rebuilt, and jettied above the cross-rail, with studding and windows similar to the parlour wing. The whole roof was rebuilt in clasped-purlin form and a chimney-stack was added at the west end.

These changes are reflected at Church Farm, Brettenham, and Clockhouse Farm, Shimplin (Johnson 1993a, 66, 68). Such alterations meant changes in circulation patterns on the ground floor and provided a substantial amount of added space to the upper storey. Johnson (1993a, 64) convincingly argues that the abandonment of the open hall in Suffolk must relate to the abandonment or modification of those social meanings and changes in the underlying social form to which they referred. The reordering of physical space reflects, therefore, a “renegotiation” (Johnson 1993a, 33-35; 2010, 92) of social relations and changes to the long-standing patriarchal order within the household (Johnson 1993a, 54), whilst also suggesting modest innovations within the craft tradition in western Suffolk.

Thomas Hubka has suggested that innovation within the craft tradition does not generally involve entirely new ideas. Rather, builders “accomplish change by reordering the hierarchy of ideas…contained within the known grammar” (1986, 430; Smith 1989). This observation on the general process of vernacular design appears to be accurate at Lower Farm, given the close similarity of date and style to other ‘transitional houses’ referred to by Johnson (1993a, 66, 68).

The closed house by contrast was “uniform and plain in both plan and detail” (Johnson 1993a, 89), and generally consisted of three bays, with lobby entry backing onto a newly inserted axial chimney-stack, and back-to-back fireplaces (1993a, 89). This type became far more prevalent as house building in general increased in the 17th century (Machin 1977, 40), with numerous regional variants on a single national theme (Roberts, 2010, 165-173; Mercer 1975; Harrison & Hutton 1984, 74; Pearson 1985, 69).

Case study: Tudor Cottage, Brent Eleigh

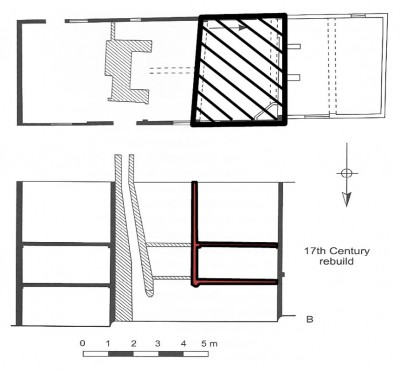

Of Johnson’s ‘closed’ type, Tudor Cottage represents a clear phasing of these changes in Suffolk. Its origins remain in the late medieval open-hall style; however, it was modified first of all with a smoke bay inserted into the open hall (Figure 4). A timber stack was then inserted into the smoke bay and a brick stack was inserted in the position of the largely destroyed timber stack, of which part of the frame survives (Johnson 2010, 91-2). A lobby entry was placed in this bay, certainly by the time of the insertion of the brick stack and possibly as part of the smoke bay, as is the pattern elsewhere (Harris 1978, 8; Alcock 1998, 82-4).

The ceiling-over of the hall gave the first floor the potential to be developed as a sphere of interaction in its own right (Barley 1991, 20-3). Such alterations saw centralization of both the circulation pattern and social meanings of the enclosed house (Johnson 1993a, 103). Activities within the closed house were drawn in, rationalized and divided according to function. This is of special interest to American scholars of the discourse, because the East Anglians of Johnson’s (1993a) ‘Housing Culture’ (1993a) played a central role in the early colonial settlement in America (Neiman 1986). Abbot Lowell Cummings (1979, 95) documents the earliest English structures erected in New England and demonstrates that East Anglian immigrants built lobby-entry houses with the same back-to-back fireplaces of Johnson’s ‘closed’ type found ubiquitously in Suffolk.

Johnson uses the key distinctions between ‘open’ and ‘closed’ houses as evidence of changing social relations and cultural mantalité. The expressive quality of the timber framed system of the open house with its visible and often noted posts and braces as at 1-2 Ufton, Warwickshire (Alcock & Miles 2012, 19-27), is completely hidden in the later ‘closed’ house (Johnson 1993a, 111).

Instead, a profusion of rooms and an increase in the amount and types of moveable furnishings became the expressive features in the increasingly private closed house (Johnson 1993a, 150; Hoskins 1953, 44). Johnson argues that the closed plan both reflected and reinforced a social distance between people formerly engaged in face-to-face relations (Johnson 1993a, 107; Longcroft 2002, 43). Put simply, gender and status relationships within households changed permanently during the 16th and 17th centuries and the design of houses reflected these changes by effectively reconciling the need for segregation and centralisation. He places this within the wider context of weakening traditional notions of authority and status and the effects of a less personal set of capitalist relations (Johnson 1996, 77-78). He contends that the transition from open to closed houses was part of a larger gradual process of enclosure, referencing new religious ideas of the Puritans concurrent with changing economic and social relations, world view, and an increasing desire for privacy (Johnson 1996, 188).

Johnson uses probate inventories to demonstrate the qualitative and quantitative difference of the older form from this new closed house, (1993a, 188), lending a tangible means by which to assess these changing meanings beyond that of the architecture of Suffolk Houses. He, like Gilchrist (2012, 114) interrogates the ‘spatial locale’ of the household, in which people lived, and the daily practices that gave meaning to their ‘life course’ (1993, 107; Gilchrist 2012, 1).

According to Johnson (2010, 138, 152), these furnishings expressed and reinforced the ideas mentioned above, gave material form to a world view and demonstrated how different groups – men and women, masters and servants – took up varying positions within this cultural milieu. Johnson (2010, 135-6) applies this to the inventory of Thomas Downton of Chetnole Farm, Dorset, but provides little beyond description of the inventory in question. In this respect, the use of probate inventories in Johnson’s work (1993a; 2010) remains, as Currie asserted of documentary use in vernacular architectural studies overall, largely unfulfilled (2004).

Nat Alcock’s (1993) ‘People at Home: Living in a Warwickshire village, 1500-1800’ expounded the use of these valuable records for the village of Stoneleigh, Warwickshire. Beyond the individual buildings and documents, Alcock reveals “how a community of English villagers organised their lives and how, within the same timber-frame as their parents, they could rearrange the rooms…to suit changing lifestyles” (1993a, 4). Inventories, therefore, appear to be the ideal tool and are often used to elucidate the social use of space (Johnson 1993a, 84, 95; Machin 1978, 160-1, Alcock & Currie 1989, 21-23). However, the house we see in an inventory is one dimensional, and located in what Alcock terms ‘a temporal vacuum’ (1993, 5). As a result, we have only a vague idea of how household goods reflect changing fashions, and meanings. For Stoneleigh, fashion and innovation have been followed through impressions, rather than statistical analysis. In the following chapters of Alcock’s book, he expands his gaze to the “building and rebuilding” (1993, 61) of many of the Stoneleigh houses, ultimately arriving at a “new style” (1993, 62) of comfortable living in Johnson’s ‘closed’ house (1993a, 89).

Case Study: The Probate Inventories of Stoneleigh, Warwickshire

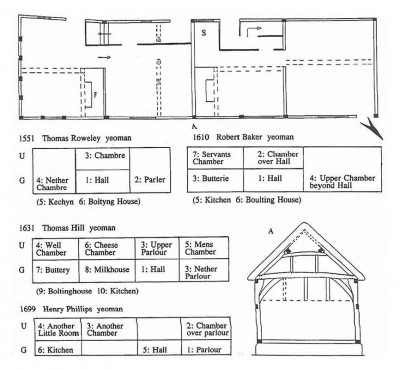

Nowhere is this better illustrated than at 11-12 Coventry Road, Stoneleigh (Figure 6). The first inventory for this holding is that of Thomas Rowley (1551). The first four rooms of the inventory describe the three-bay house, complete with central hall, parlour, chamber, and nether chamber. The inclusion of apparel, silver and wool here suggests a separation between these first rooms and the last two, something noted by Alcock (1993, 69) as highly rare for inventories as early as this. The kitchen and bolting house were located in a detached service block. In 1610 the inventory of Robert Baker lists only one extra room, though records a notable number of farm buildings.

The changes since 1551 were small, but characteristic, and included the insertion of a second upper chamber and the conversion of a ground floor chamber to a buttery. By the time Thomas Hill inherited, the house certainly included an easterly extension. His inventory in 1631 shows great improvements, most prominent of which was the glazing of the hall windows. The house now had three more rooms, a dairy and two more chambers, typical improvements for this period (Longcroft 2002, 45). The bolting house and the kitchen were again listed last, presumably remaining separate from the house. The latter contained the cheese press and brewing ‘fatt’; however cooking now took place within the buttery. In 1699, the inventory of Henry Phillips only lists six rooms, though the omission of some rooms in the main block means that we cannot be sure that the detached kitchen and bolting house were removed.

Though the detail Alcock provides of his Warwickshire inventories is good, it is approached functionally and largely in terms of architecture; lacking the theoretical edge Johnson (1993a) delivers. Little is made of the socio-cultural meanings behind the groups of objects themselves, and that which does so, is disjointed from the inventories he presents (Alcock 1993, 172-194). In any case, highlighting these minor shortcomings is not to denigrate Alcock’s triumph, but merely to suggest an approach characterised by both a detailed use of probate inventories — Johnson’s highly theoretical, structuralist perspective — and Roberta Gilchrist’s “materiality and domesticity” (2012, 114).

There can be no doubt that the legacy of W. G. Hoskins played an integral role, not only in the historical and archaeological legwork of Johnson’s work; but also the ultimate methodology of the discourse (Dyer 2006; Alcock 1993; Machin 1977). The ‘Great Rebuilding’ still endures as an idea, because W. G. Hoskins approached his Suffolk houses from a documentary perspective as human products. He acknowledged what Johnson did fifty years hence, that the social meanings embedded in vernacular architecture can elucidate the diverse transitional period in which closure of the open hall occurred. However, Hoskins was corseted by the frameworks of his time, and it was not until the advent of post-processualism that the theoretical approaches now used by Johnson became available. In looking to American vernacular discourse (Deetz 1977, Glassie 1975), Johnson was able to successfully apply structuralist and post-structuralist linguistics (Saussure 1983) to the meanings Hoskins attempted to tease out of the vernacular houses of Suffolk. From the highly theoretical, contextualised practice of a generative grammar and the underlying competence of buildings, Johnson presents a compelling interpretation of how and, most importantly, why these meanings changed and were manifested in the architecture from 1300 to 1800 (2010, 187). Johnson’s assessment of the form, fabric, and expressive quality of ‘open’, ‘transitional’ and ‘closed’ houses challenges the hitherto ‘commonsensical’ (1990, 253; Gerrard 2003, 173) explanations about architectural change based on the rise of privacy and comfort in the modern age. Instead, cultural change was postulated to be at the core of the underlying changes in domestic space. The attempts to extend this context into the landscape are, at this stage, fairly unconvincing, and require application elsewhere to determine how fruitful an endeavour this is. It is true to say also that Johnson’s examination of probate inventories lacks the rigor and detail of Alcock’s, though conversely, the absence of theoretical interpretation in Alcock’s work is stark. Roberta Gilchrist (2012), by contrast, offers a highly profitable approach to the objects in space Johnson was presumably attempting to achieve, whilst also theoretically informed. Nonetheless, Johnson’s highly reflexive, socially influenced theory of ‘closure’ can only be strengthened by such works, all of which in conjunction (Johnson 1997, 18) constitute the most useful approach to vernacular architecture.

Bibliography

- Alcock, N.W. (1983). The Great Rebuilding and its later stages. Vernacular Architecture. 14, 45-48.

- Alcock, N.W. (1993). People at home, living in a Warwickshire village 1500-1800. Chichester: Philllimore.

- Alcock, N.W. (1998). Smoke bay or open hall? Cuttle Pool Farm, Knowle, Warwickshire. Vernacular Architecture. 29, 82-84.

- Alcock, N.W. and Miles, D. (2012). An early 15th century Warwickshire cruck house using joggled halving. Vernacular Architecture. 43, 19-27.

- Alcock, N.W. and Currie, C. (1989). Upstairs or downstairs? Vernacular architecture. 20 (1), 21-23.

- Alcock, N.W. and Laithwaite, M. (1973). Medieval houses in Devon and their modernisation. Medieval Archaeology. 17, 100–125.

- Barley, M.W. (1991). The use of upper floors in rural houses. Vernacular architecture. 22(1), 20-3.

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Coleman, S. (1979a). Suffolk Houses a study of domestic architecture. Vernacular architecture. 9, 16-17.

- Coleman, S (1979b), Post—medieval houses in Suffolk. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. 34, 181–90.

- Cummings, A.L. (1979). The framed houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1675. London: Harvard University Press.

- Currie, C. (1988). Time and chance: modelling the attrition of old houses. Vernacular architecture. 19, 1–9.

- Currie, C. (2004). The Unfulfilled Potential o