The temple of Roma and Augustus (dated to the late 1st century BC) was the sole major architectural supplement to the 5th and 4th century building complex on the Athenian Acropolis (Spawforth 2006, 144). Despite this, the temple has rarely been discussed in scholarly writings in contrast to the vast literature dedicated to other structures on the Athenian citadel, such as the Parthenon or the Erechtheion. Those who have granted it attention have often, but not exclusively, seen it as a symbol of Romanization, a concept which likely needs further rethinking (Spawforth 1997,183,192; Mattingly 2006, 17; Webster 2003). While the building has largely been viewed as either a monument to Roman power or a skillful Athenian subornation of Augustus’ victory into Athenian past glory, it was arguably both: not simply an indication of Romanness but a negotiation of mixed Athenian feelings (Keen 2004; Hurwit 1999, 279-280). This brief paper will investigate the extent to which the temple of Roma and Augustus on the Acropolis can be seen as a symbol of Roman power by examining its architecture and topographical context.

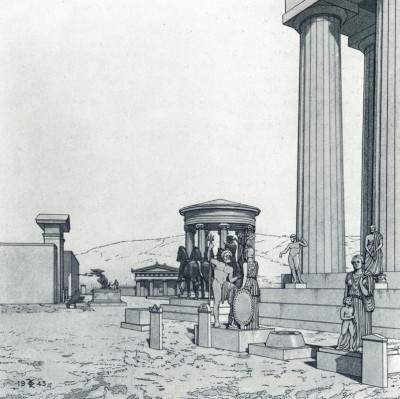

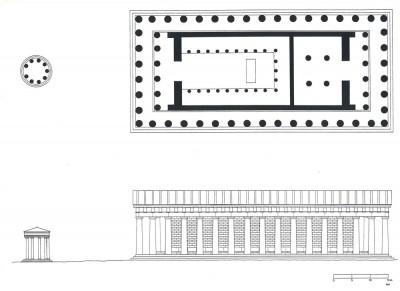

The temple of Roma and Augustus was a circular, lonic, marble structure (Figures 1,2,3) (Travlos 1971, 494). The inscription tells us that: “The people [Athenians, dedicated the temple] to the goddess Roma and Caesar Augustus...” (IG II2 3173 in Camp 2001, 187). Although the building does not fully survive, making architectural inferences rather conjectural, its diameter and height likely measured 7.36m, indicating a sizeable structure (Hoff 1996, 188). There is much debate over the temple’s precise date, the most likely being around 20/19 BC (Hoff 1996, 189-194).1

The temple was constructed in the context of a troubled Augustan-Athenian relationship. Dio says that in the winter of 22/21 BC Augustus visited Athens, at which time the statue of Athena in the Parthenon, which usually faced eastward, turned west, and spat blood in Rome’s direction (Dio 54.7.3). His story (obviously fictional) suggests Athenian opposition to Rome or Augustus personally. In the same visit, Augustus, who stayed in Aegina rather than Athens, confiscated Athenian territories (i.e. Aegina and Eretria), in addition to withholding Athens’ previous right to sell Athenian citizenship (Huber 2011, 211; Hoff 1989, 4). Hoff has interpreted these actions as repercussions, albeit moderate, fueled by Augustus’ dissatisfaction (possibly also due to past Athenian support of Anthony) with anti-Roman feeling (Hoff 1989, 4; Spawforth 2006, 144). In 19 BC, Augustus returned to Athens after his diplomatic victory over Parthia, at which time he participated in the Eleusianian Mysteries, indicating his anger had diminished (Hoff 1989, 4; Schmalz 2009, 80). The temple of Roma and Augustus likely coincides with this second visit (Hoff 1996, 193-194). Scholars have suggested its construction, honoring the emperor by instituting the imperial cult on the Acropolis, was a sign of Athenian loyalty aimed at softening Augustus’ anger (Spawforth 2012, 83; Schmalz in Spawforth 1997, 193).

The surviving architectural features echo Greek architecture. The Ionic columns with their ornately chiseled floral elements are clear, and rather poor, imitations of the columns from the eastern porch of the Erechtheion, making this one of the earliest examples of “classicizing” at Athens (Spawforth 2006, 144; Camp 2001, 187). The inscription, the only indicator of the temple’s existence, is incised in pseudo-stoichedon style, imitating archaic script (Bowersock in Arafat 1996, 29). Additionally the temple was constructed of Pentelic marble, acquired from the quarries of nearby Mount Pentele and used widely in Classical Athens (Hurwit 1999, 317; Sturgeon 2006, 119-120). For instance, the major structures of the 5th century Periclean building program on the Acropolis were erected out of primarily Pentelic marble (e.g. the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, and the Temple of Athena Nike) (Sturgeon 2006, 127, 139, 142).

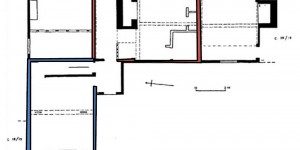

The temple’s location is extremely significant in deciphering its meaning. Firstly, the location links the imperial cult with that of Athena (Whittaker 2002, 26). The structure was axially aligned with the eastern entrance of the Parthenon, placed 23m eastward (Figures 4) (Hurwit 1999, 279).2 This link connected imperial cult to the center of Athenian political and religious life and to Athens itself: the polis and its patron goddess were intimately tied, as the worship of the latter reinforced the former’s identity (Whittaker 2002, 26). Scholars have acknowledged that the construction of a temple, in the center civic space, was a representation of the city’s collective identity (Spawforth 2006, 12, 27, 48; also Osborne 2009). The Parthenon, with its layers of meanings, was above all the ultimate expression of Athenianness. Therefore a link between the imperial cult, the cult of Athena, and the Parthenon, was a link to the city of Athens, its constituents, and its past (Whittaker 2002, 26).

The temple’s location also assimilates it into the Acropolis’ “field of victory” (Hurwit 1999, 281). The Parthenon east end metopes showcase the Gigantomachy, portraying the rebellious giants – likely representing disorder equated with the uncivilized – whose hubris led them to challenge the gods i.e. order (equated with the civilized) and be defeated (Camp 2001, 78; Watrous 1982, 160; Fullerton 2000, 55). In conjunction with its other metopes3 and the glorification of the patron deity, Athena, on both pediments, the Parthenon can be read as a victory monument of the civilized–or in this case the Athenian-over the eastern ‘barbarians’ (i.e. the Persians) (Camp 2001, 77-79). This theme, while only alluded to in the 5th century, was further enhanced by later dedications on the Acropolis such as the shields of the Persians fixed to the Parthenon’s architrave after Alexander had defeated them at Granikos, or the Attalos I’s dedications of bronze groups of Athenians against Persians, Gods against Giants, and Greeks against Amazons (Rose 2005, 50-51; Robertson 1985, 179-180). Such future dedications both strengthened the Parthenon’s theme of triumph over the east, and created a field of monuments on the southeastern corner of the citadel, framed by a view of Salamis in the background which, as a major battle setting against the Persians, would add to this theme (Ibid). The temple of Roma and Augustus was established at the time of Augustus’ return from his diplomatic victory over Parthia (see above). Hurwit argues that the Parthians were just another loser in the theme of victory against the eastern barbarians and that the temple can be seen as a victory monument of Rome (and Augustus) against the east, making it a part of the “field of Nike” created over the ages (1999, 280; Hoff 1996, 194).

The meaning of the location of the temple through (a) its incorporation into the theme of victory and (b) its connection to Athena on the Acropolis, can be dually read. Keen suggests that the temple’s distinctive round form (contrasting with the non-circular buildings nearby) and its primary location directly in front of the Parthenon, which added to its attraction, would, “suborn Athenian civic space to the purposes of Rome.” (2004, 4; Pedley 2005, 217). Contrastingly, Hurwit suggests that the Athenians, while “sincerely honoring” Augustus and Rome, were also suborning his victory into the Parthenon’s and the Acropolis’ age-old symbolism of victory over the east (199, 280). Augustus’ triumph was hence simply the latest demonstration of Athens’ (Ibid).

Compared to the Parthenon the Augustan temple appears inferior in execution, as is suggested by the arguably sloppy copies of the Erectheion columns, and rather small (Figure 5) (Kajava 2001, 82; Hurwit 1999, 279). It is possible the temple was small simply because of the limited space available on the Acropolis (Keen 2004, 3-4). Whether this is true or not, it does not change the fact that the round temple would in comparison to the dominating Parthenon behind it, appear less grand and hence less significant. Its circular structure would indeed draw the eye, as Keen has suggested, but it could also draw the visitor to the comparative greatness of the Parthenon (Ibid). It would then emphasize, by relation, the glorious architecture of Athens’ past and therefore Athens’ past power. The Parthenon after all was a manifestation of all that Athens used to be. The temple of Roma and Augustus, constructed by Athenians, could then appear as a manifestation of Rome’s lesser power in comparison to the past power of Athens itself.

The construction of the temple of Roma and Augustus, with its possible multiple interpretations, could reflect the conflicting feelings of the Athenians to both respect and acknowledge the power of Augustus (and Rome) but simultaneously not diminish their culture and history, thus maintaining their identity. In light of a strained Athenian-Augustan relationship, the Athenians, in part to soften Augustus’ dissatisfaction with past Athenian actions, constructed a temple in their own architectural language, and instituted the imperial cult on the Acropolis. By doing so they honored Augustus and Rome and acknowledged Rome’s current power and their current subjugation to it. Beneath this servility, the Athenians managed to once more manifest, by comparison, their own significance. The temple of Roma and Augustus can be seen as both a symbol of Roman power and an indirect reminder of Athens’ great past.

1 For a full summary of the date debate see Whittaker, 2002.

2 The inscription strengthens this connection by also mentioning the current priestess of Athena, Polias, on the Acropolis.

3 The other metopes of the Parthenon are the Centauromachy, or Greeks fighting centaurs (on the western side), the Amazonomachy, or Greeks fighting Amazons (on the southern side), and Greeks fighting Trojans (on the northern side) (Camp 2001, 78).

Bibliography

- Arafat, K.W. (1996). Pausanias’ Greece, Ancient artists and Roman rulers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Camp, J. (2001). The Archaeology of Athens. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Cassius Dio. (1990). The Augustan Settlement (Roman History 53-55.9). Trans. J. W. Rich. England: Aris & Phillips Ltd.

- Fullerton, M.D. (2000). Greek Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoff, M. (1989). The Early History of the Roman Agora at Athens. In S. Walker and A. Cameron (Eds). The Greek Renaissance in the Roman Empire: Papers from the Tenth British Museum Classical Colloquium. BICS Supplement 55. 1-8.

- Hoff, M. (1996). The politics and architecture of the Athenian imperial cult. In P. Foss and J.H. Humphrey (Eds). Subject and Ruler: The Cult of the Ruling Power in Classical Antiquity. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement. 17. 185-200.

- Huber, M. (2011). Rome Becoming Athens, Athens Becoming Rome: Building Cultural Reciprocity in the Augustan Period. Chrestomathy. 10, 204-219.

- Hurwit, J.M. (1999). The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic era to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kajava, M. (2001). Vesta and Athens. In O. Salomies (Ed). The Greek East in the Roman Context, Proceedings of a Colloquium Organised by the Finnish Institute at Athens, May 21 and 22, 1999. Papers and Monographs of the Finish Institute at Athens. 7, 71-94.

- Keen, T. (2004). The Temple of Roma and Augustus on the Acropolis, or What’s the Use of A Propaganda Monument Nobody Notices?. The Open University Classical Studies Department Associate Lecturers’ Newsletter, 1-6.

- Mattingly, D. (2006). An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC- AD 409. London: Penguin Books.

- Osborne, R. (2009). Greece in the Making, 1200-479 BC. London: Routledge.

- Pedley, J. (2002). Greek Art and Archaeology. London: Laurence King Publishing.

- Pedley, J. (2005). Sanctuaries and the Sacred in the Ancient Greek World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robertson, M. (1985). Greek art and religion. In P.E. Easterling and J.V. Muir (Eds). Greek Religion and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 155-190.

- Rose, C.B. (2005). The Parthians in Augustan Rome. American Journal of Archaeology. 109 (1), 21-75.

- Schmalz, G.C.R. (2009). Augustan and Julio-Claudian Athens: a new epigraphy and prosopography. Leiden: Brill.

- Snodgrass, A. (1977). Archaeology and the rise of the Greek state: an inaugural lecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Snodgrass, A. (1980). Archaic Greece: The Age of Experiment. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

- Spawforth, A. (2012). Greece and the Augustan cultural revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Spawforth, T. (1997). The Early Reception of the Imperial Cult in Athens: Problems and Ambiguities. In M. C. Hoff and S. I. Rotroff (Eds). The Romanization of Athens: Proceedings of an International Conference held at Lincoln, Nebraska (April 1996). Oxbow Monograph 94. 183-202.

- Spawforth, T. (2006). The Complete Greek Temples. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Stevens, G. P. (1946). The Northeast Corner of the Parthenon. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 15 (1), 1-26.

- Sturgeon, M.C. (2006). Archaic Athens and the Cyclades. In O. Palagia (Ed). Greek Sculpture: Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 32-76.

- Travlos, J. (1971). Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Walker, S. (1997). Athens Under Augustus. In M. C. Hoff and S. I. Rotroff (Eds). The Romanization of Athens: Proceedings of an International Conference held at Lincoln, Nebraska (April 1996). Oxbow Monograph 94. 67-80.

- Watrous, V. (1982). The Sculptural Program of the Siphian Treasury at Delphi. American Journal of Archaeology, 86 (2), 159-172.

- Webster, J. (2003). Art as Resistance and Negotiation. In S. Scott and J. Webster (Eds). Roman Imperialism and Provincial Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 24-51.

- Whittaker, H. (2002). Some Reflections on the Temple to the Goddess Roma and Augustus on the Acropolis at Athens. In E.N. Ostenfeld (Ed). Greek Romans and Roman Greeks: Studies in Cultural Interaction. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. 25-39.