The mystery cult of Mithras was a religious phenomenon that was, for the most part, propagated through, and associated with, the Roman military. Many inscriptions and temples on the frontiers of Rome indicate that it extended from Britain to Dura Europos, and from the Rhine to the Nile over three centuries (Clauss 2000, 16). The Temple of Mithras in the Walbrook stream valley was perhaps the largest and most significant Mithraeum found in Britain, despite being an accidental discovery (Shepherd 1998, 13). Peculiarly, this Mithraeum’s location and size suggest that the nature of the cult might not have been as firmly connected with the Roman army as once thought. Mithraism was affected and influenced by local practices, gods and social changes within the Roman Empire, as will be made clear in some of the iconography discussed below (Clauss 2000, 16).

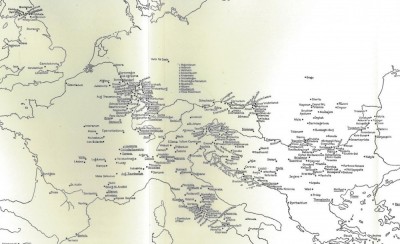

Four legions were originally stationed in Britain but, after the first century this was reduced to three. During the next three centuries they gradually decreased in size (Mattingly 2006, 130-131). Initially they were the II Augusta, XIV Gemina (Martia Victrix post 61CE), the XX Augusta (Valeria Victrix post 61 CE) from Lower Germany, and the IX Hispana from Pannonia; six legions in total are attested to have served in Britain including the II Adiutrix and VI Victrix (Daniels 1975, 249). Therefore there was ample opportunity for the influx of different cult practices. Of particular interest are the XX and IX legions that came from Pannonia and Germany; these areas possess some of the earliest evidence for Mithraism in the first century CE (Daniels 1975, 250). Dedicatory inscriptions and Mithraea were found along many sites near Hadrian’s Wall such as; Luguvallium (Carlisle), Petrianae (Stanwix), Longovicium (Lanchester), Corstopitum (Corbridge), and Camboglanna (Castlesteads) (Vermaseren 1956, 283). The Rhine and the Danube (Pannonia Superior and Dacia, Figure 1) show a similar pattern. The London Mithraeum contributes greatly to the understanding of religion in Roman Britain; the temple is an enlarged version of the standard Mithraeum and its location indicates that a military and merchant following were likely.

Franz Cumont considered Roman Mithraism to have stemmed from the Persian god Mitra of the Hittite Empire, his conclusions are based upon the Avesta and other Persian texts (Cumont 1896). Cumont in the late 1800s wrote on Mithraism and used Persian texts to understand the iconography of Roman Mithraism. Gordon states that, although very important to the study of Mithraism, it was recently recognised that the cult was not primarily an offshoot of the Persian cult and that this connection, though significant, need not be emphasized to a great degree (Gordon 1975, 219). The god personified the idea of a treaty or contract; and in Persia, c. fifth century BCE, he was equated with the Sun. However, as Manfred Clauss argues, the Roman cult was an independent creation that neither stemmed from Persian religious customs nor was it a precursor for Christianity (Clauss 2000, 7). In the west it was a mystery religion, which was not the case in Persian worship until after 150 CE (Irby-Massie 1999, 74). Merrifield argued that the iconography of Mithras slaying the bull actually derived from scenes of Nike slaying a bull; the earliest evidence was Trajanic and also contemporary with the earliest evidence of Mithraea being built (Gordon 1996, 65).

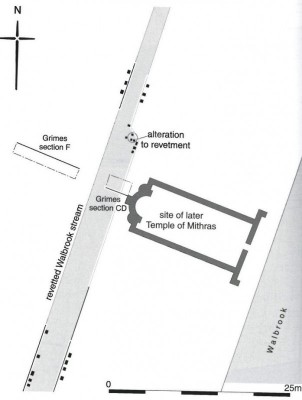

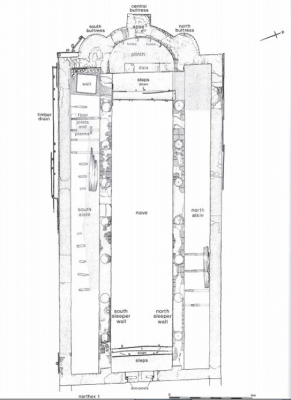

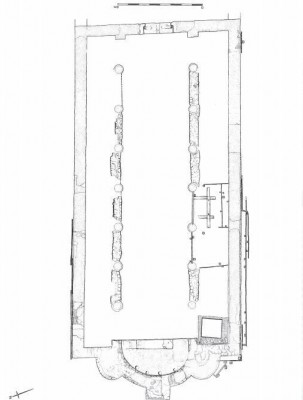

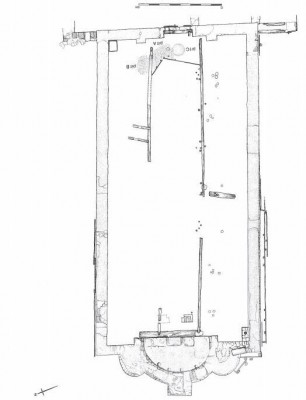

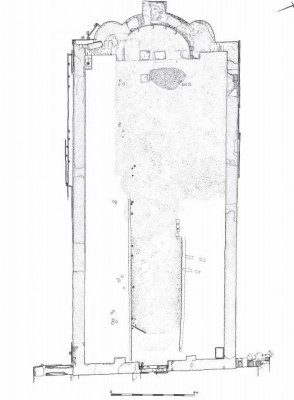

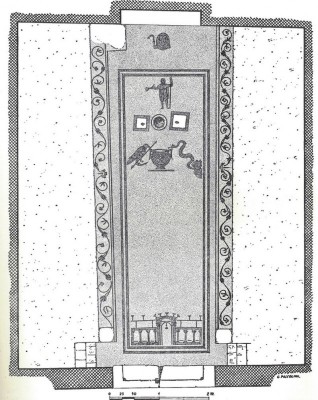

London witnessed significant depopulation in the late second century followed by major public building works and a slight recovery in the late third to early fourth century (Merrifield 1983, 172). The Temple of Mithras was built in 240-250 CE, which is attested to by the early third century pottery, analysed by Joanna Bird, and a sestertius of Hadrian which provide a terminus post quem (Shepherd 1998, 47). The temple was located north of the Thames, west of the Forum Basilica, south east of the fort at Cripplegate and lay was set perpendicular to the Walbrook stream (Figure 2) (Shepherd 1998, xvii). The modern disturbances of the site were No. 7-9 Walbrook, of which the foundations for the walls truncated the walls of the Mithraeum and eradicated much of the post Roman stratigraphy (Shepherd 1998, 54). The temple’s chronology is divided into four phases: Phase I (Figure 3), Phase IIa (Figure 4) and Phase IIb (Figure 5), Phase III (Figure 6), and Phase IV (Figure 7) (Shepherd 1998, 73-96). They indicate the changing function and the major changes made to the internal layout and features of the temple over time.

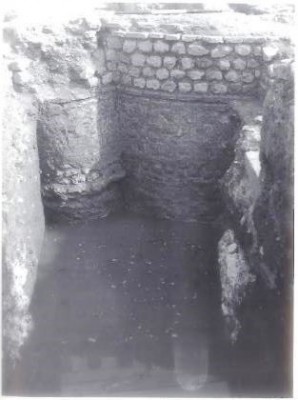

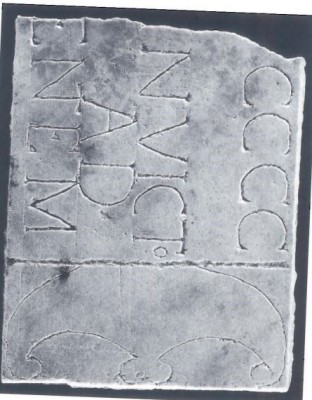

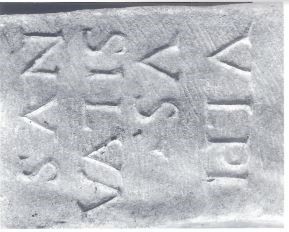

The layout of the temple needed to account for the unstable ground during construction and also in the late third century, when the building suffered a collapse of the south western ceiling. Instability was caused by ground water and subsidence due to the temple’s proximity to the stream. The construction of the temple was fairly standard in that the foundations, walls, buttresses, apse and sleeper walls were constructed with mortar, ragstone and tile. Mortar was placed first with ragstone above, then ragstone and tile courses (Figure 8) (Shepherd 1998, 58-59). The effects of the ground’s instability were signalled by the sleeper walls and apse constructed with three buttresses (Shepherd 1998, 58). The building was 58.5 feet long by 26 feet wide. Like many Mithraea, the temple was orientated east to west. There was also evidence of wooden planks in the north and south aisles which could have been benches (Grimes cited Shepherd 1998, 63). Many other Mithraea have benches as well; Carrawburgh, Rudchester, and on the mainland, Nida (Heddernheim) are some examples (Figure 9). Significant changes occur in Phase III (late 3rd century CE), the collapse, the columns were removed, the cult icons were buried in Floor 5 (Figure 6), and the west end was rearranged (Figure 6) (Shepherd 1998, 227). In the early fourth century the layout became more open; evidenced in Floor 6a by a slab with INVICTO inscribed on it, dating 307-308 CE (Figure 10). Floor 3 raised the level to the top of the steps to the nave signalling the end of the sunken nature and by Floor 5 the well was covered (Shepherd 1998, 72, 225). Whether this signalled the end of the temple functioning as a Mithraeum is debatable. The Bacchic sculptures and votive offerings suggest that it was no longer a Mithraeum as argued by Henig (1998, 230).

The temple did not have windows or they were very small and high up to reduce light (Shepherd 1998, 89). Rudchester, Carrawburgh and the London Mithraea were also dated to the third century, and reflect the general trend of Mithraea in the northwest provinces, where apses and rectangular niches were mainly found. Phases I and II of the Rudchester Mithraeum both include an apse with benches, and what appear to be sleeper walls. At Carrowburgh, the original temple was small and square, but later Phases, such as Phase IIa, have an elongated plan, a square niche, as well as benches. In Italy, the Mithraeum of Felicissimus, Ostia, does not have a projecting apsidal end but instead an apse right of the entrance (Figure 11) (Shepherd 1998, 226). Columns were most likely more for the superstructure’s stability, but they may have had a ritual use as well. The London Mithraeum has seven columns, which may represent the seven grades of the cult. In comparison, the Mithraeum at Ostia has eight panels of mosaic on the floor representing the seven grades with one dedicatory panel (Figure 11) (Shepherd 1998, 225). Another Mithraeum in Ostia, Sette Porte, has a mosaic on the floor of seven gates, which furthers the connection of the cult with the stars, planets and astronomy (Figure 12) (Vermaseren 1956, 138).

The architecture of Mithraea was intimately linked with the sacred narrative of Mithras. In the cave, Mithras killed the bull which was clearly connected with the arrival of life and light. Several inscriptions upon altars and votive offerings, such as an altar from Housesteads (Coulston and Phillips, 1988) and Whitley Castle, were dedicated to Sol Invictus, “Deo Invicto Mytrae” and Deo Soli Invicto (Wright 1943, 37). An inscription from Isca in Wales (CIMRM 809) was dedicated to Deo Invicto Mithrae from the II Augusta (Vermaseren 1956, 284). Therefore, the ability to control the amount of light that entered the temple was essential to Mithraism’s mythical story; the coming of life and light out of darkness was created by these conditions in their temples. One of the few ancient sources on Mithraism was from Porphyry. In his De Antro Nympharum 6, the Persian cult’s temple was described as a symbol of the cave where Mithras slayed the bull and as a model of the universe that he created.

With this in mind, the Mithraeum at London and others in Italy and the frontier reflected this setting. Firmicus Maternus in Error of the Pagan Religions mocked the cult for initiating members within a murky cave away from the light. Despite the fact that he was mocking and denouncing the cult, it does provide further proof that the cave setting had religious significance to Mithraists. Candlesticks were also found (Shepherd 1998, 90, 178). Furthermore, water was also essential to the mystery cult and so many Mithraea are located near springs such as Poetovio, Pannonia Superior, Mackwiller, Gallia Belgica and Housesteads. They also have water basins or urns such as at Carrawburgh (Figure 9) (Irby-Massie 1999, 78). The London Mithraeum’s location next to the Walbrook stream supports this (Figure 1) (Vermaseren 1956, 283).

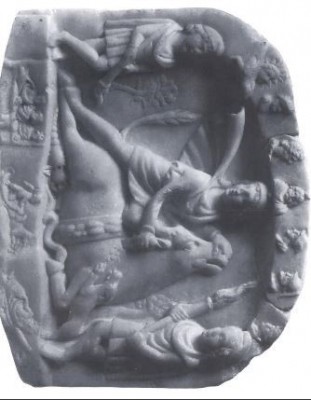

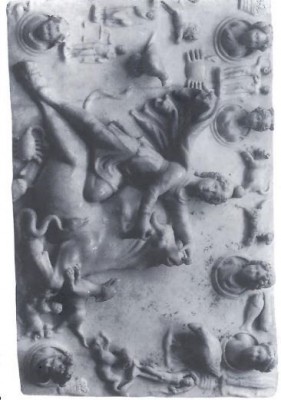

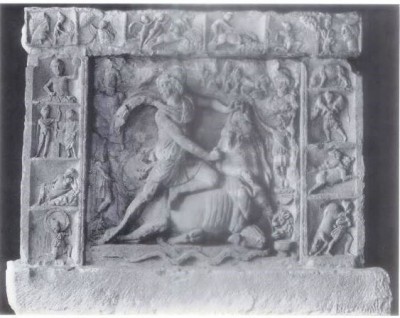

In London, the Mithras Tauroctonos with the zodiacal cycle was dedicated by Ulpius Silvanus of the II Augusta, apparently appointed at Orange (Figure 13 and 14) (Clauss 2000, 89). This scene was found at many Mithraea and it contains astronomical symbols, which were well attested at other sites. A relief found in Bologna (Figure 15) of unknown provenance contains the planets in the reverse order of the weekdays; other reliefs with astronomical symbols have been found in Sidon, Dura Europos, Brigetio (Szony, Hungary) and Rome (Figures 16, 17, and 18) (Clauss 2000, 87).

The Tauroctonos has spurred the idea that the reliefs were “star maps” (Clauss 2000, 87). For example, the scene contains Cautes, Cautopates, Sol rides up to heaven on the right, Luna downwards with her oxen, and all the parts of zodiac are present as well (Clauss 2000, 88). A sculpture of the Tauroctonos from Rome (Figure 19) showed ears of corn coming from the bull’s wounds while the snake and dog direct themselves toward them (Vermaseren 1956, 225). Thus the creation of life was connected with the cosmos. At many Mithraea, stars were depicted on the ceiling in order to evoke the cosmos; for instance at Virunum where a plaque records its highly decorated ceiling. Beck stated that the stars were also to represent their deceased colleagues who have ascended to immortality (Beck 2004, 360).

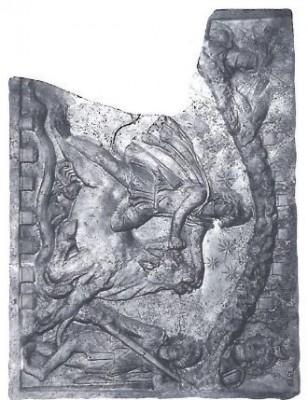

Mithraism was a malleable and tolerant religion which revealed the influx of other deities and religions in their iconography. Some depictions of Mithras portray him with a bow, hunting; a scene not often seen, if at all in Britain. Scenes of hunting and Mithras were found mainly in the areas of the Rhine, Danube and the Near East at places such as Dura Eruopos (Figure 20), Neuenheim (Figure 21), and Osterburken (Figure 22) (Vermaseren 1963, 90). Location was a factor and Mithraea were located near other shrines, Albachtal of Trier for example, suggesting that there might have been friendly relations if not assimilation (Henig 1998, 232).

Evidence of a ritual meal is supported by chicken, sheep, cattle, pig and dog bones found scattered throughout the floors with a slight decrease in the post Mithraeum layers; many chicken bones were found at Carrawburgh as well (Shepherd 1998, 227, 247). Furthermore, in the ante room at Carrawburgh was a hearth with charcoal and ashes; similarly a small kitchen was found in the Lentia Mithraeum complex in Austria and Ostia suggesting a ritual meal was cooked within the temple (Vermaseren 1963, 41).

The London Mithraeum shows some evidence of clearly defined burned areas such as in Floor 2, and to conclude it was for a ritual meal would be convenient, but the evidence was not conclusive (Shepherd 1998, 74). Regardless, the evidence of animal bones in London and other temples indicates the presence of a ritual meal. Unfortunately, the narthex of the London temple could only be partially excavated due to its proximity to the edge of the site (Shepherd 1998. 95). Perhaps further excavation of the area could provide evidence for a similar function to the ante room at Carrawburgh.

Perhaps most telling of the temple’s function as a Mithraeum were the sculptures of Mithras, Serapis, Mercury, Minerva and a “water deity,” which could have been Oceanus (Shepherd 1998, 171-172). The sculptures were likely to have been carved in Italy; an isotopic analysis of these sculptures has indicated that many originated from Carrara or Docimaeum quarries (Shepherd 1998, 109). Therefore, it was argued that the Mithraeum was built by a Roman official who came to Britain and brought his religion with him (Merrifield 1983, 187). This is a pleasant idea which the isotopic evidence and relative dating of the sculptures support, but Mithraism was popular elsewhere in Britain at the same time and an establishment run by, and even for, the local military and veterans in London, seems more likely. The dedication by Ulpius Silvanus seems to indicate that the nature of the Mithraeum in London was likely characterized by a military following but possibly also a merchant one, evidenced by the temple’s location. However, the fort in London was found by Grimes to be incorporated into the city’s defences and was sparsely occupied during the third century (Grimes 2011). Therefore, if the military presence in London was reduced at the time of the Mithraeum’s construction, the initiations may have not been primarily military and perhaps more merchantile. A comparable location is Ostia, also a port town, where at least 17 Mithraea have been found (Laeuchli 1968, 73). However, because these were port sites, the movement of people, and more notably troops, through them could also testify to their construction by or for the military. At Rome and Ostia, there were dozens of Mithraea which suggests that Mithraism did not have only a military following (Laeuchli 1968, 73).

The shifting layout of the temple in the fourth century and the burial of religious items (the head of Mithras or Serapis, for example), was argued to signal the end of it functioning as a Mithraeum and the possible beginning of a Bacchic temple. The connection between Mithras and Bacchus could be further elaborated as the juxtaposition of Mithraic and Bacchic material occurred at Apulum, as well as London according to Haynes (2008). Further excavation of the area within and around the Mithraeum at London would considerably further an understanding of Mithraea and the cult in Roman Britain. The very fact that the London Mithraeum was not definitively associated with the military leaves many questions unanswered. A connection between the Roman military in London is not a sufficient explanation for the Mithraeum’s genesis and development. Yet, the hierarchical structure of Mithraism suited the Roman military well, and in Britain the majority of the temples and inscriptions were found in close proximity to military sites and dedications came from military officials (Mattingly 2006, 215). Therefore, the Mithraeum in London was an exceptional temple in terms of location, contents and its contribution to the study of Mithraism in the Roman Empire and Britain. The size and construction of the temple cannot be discounted because archaeological evidence of Mithraea across the Roman Empire revealed that Mithraea were markedly smaller than the one in London.

Bibliography

- Clauss, M. (2000). The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries. Tr. Gordon, R. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Coulston, J. C. and Phillips, E.J. (1988). Hadrian’s Wall West of the North Tyne, and Carlisle. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cumont, F. (1896). Textes et Monuments Figures Relatifs aux Mysteres de Mithra Vols I and II. Bruxelles : Lamertin:.

- Daniels, C. M. (1975). The Roman Army and the Spread of Mithraism. Mithraic Studies Vol II. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Gordon, R. (1975). Franz Cumont and the Doctrines of Mithraism. Mithraic Studies Vol I. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Haynes, I. (2008). Sharing Secrets? The Material Culture of Mystery Cults from Londinium, Apulum and Beyond. In J Clark (ed) Londinium and Beyond. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Henig, M. (1998). Appendix 1 The Temple as a Bacchium or Sacrarium in the Fourth Century. The Temple of Mithras: Excavations by W.F. Grimes and A. Williams at the Walbrook. London: English Heritage.

- Irby-Massie, G. L. (1999). Military Religion in Britain. Boston: Brill.

- Laeuchli, M. (1968). “Urban Mithraism.” The Biblical Archaeologist Vol. 31. No. 3, .73-99.

- Mattingly, D. J. (2007). An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, 54 BC-409AD. London: Penguin.

- Merrifield, R. (1983). London: The City of the Romans. London: Batsford.

- Merrifield, R. (2008). In its depths, What Treasuers-The Nature of the Walbrook Stream Valley and the Roman Metalwork Found Therein. In J Clark (ed) Londinium and Beyond. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Shepherd, J.D. (1998). The Temple of Mithras: Excavations by W.F. Grimes and A. Williams at the Walbrook. London: English Heritage.

- Ulansey, D. (1989). The Origin of the Mithraic Mysteries: Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vermaseren, M.J. (1956). Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae. Hagae Comitis: M. Nijhoff.

- Vermaseren, M.J. (1963). Mithras, The Secret God. London: Chatto and Windus.