Until the middle of the fourteenth century, most houses in towns contained a shop fronting the street (Clarke 2000, 59; Rees Jones 2008, 68). The approaches used in the analysis and interpretation of these have changed over time with historians and archaeologists drawing on an increasing range of analytical methods from a number of disciplines in order to interpret and understand the form and meaning of buildings. The findings however, are equivocal. This paper will discuss the changing approaches to the analysis and interpretation of medieval urban housing occupied by those at the lower to middle end of the social scale, in order to show the complex considerations that influence our understanding.

Plan form typologies

The first seminal work concerning medieval town houses was that of Pantin (1962-3), in which he used documentary evidence and archaeological surveys to classify two sub-groups of town houses by their plan form. Concentrating on middle sized houses of the late 13th to early 16th centuries with a hall open to the roof, he produced a classification based on whether the hall was parallel to or at right angles to the street. Pantin’s interpretation of the origin of these house types was that they were adapted from country house types to meet urban conditions (Pantin 1962-3, 202), but his failure to include non-hall houses may have either biased this conclusion or been a strategy for proving his hypothesis.

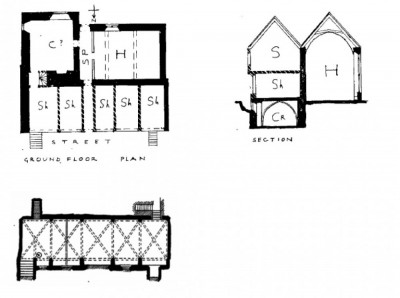

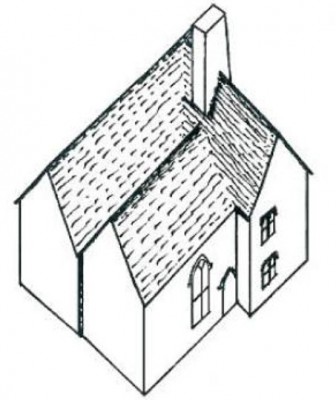

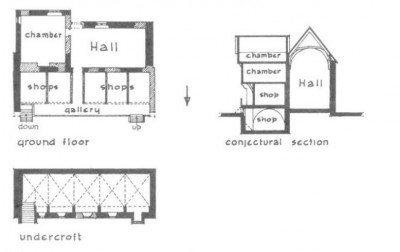

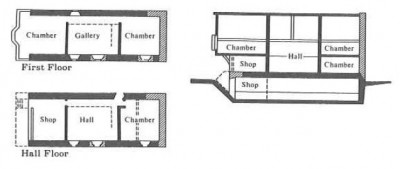

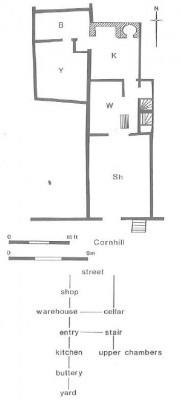

Faulkner’s (1967) research of 13th and 14th century town houses was concerned with buildings that had split level shops on the lower two levels and domestic accommodation above, and could be considered as an extension of Pantin’s work. In his examples the undercroft formed the lowest level of the building, and the ‘ground’ floor of the building was above street level and accessed by a stair (Faulkner 1967, 122). Contractual evidence and consideration of access strategies indicated it was usual for the undercroft to be separately tenanted to the shop above, and sometimes the shop was also separately tenanted to the domestic accommodation (Faulkner 1967, 122-123; 127).

Schofield’s typology (1987) is also a development of Pantin’s plan types. Using the Treswell surveys of London from 1607-14, he presented four types, Types 2 and 3 being closely based on Pantin’s Types I and II. He added the types Pantin omitted however, thereby broadening the range of size and social status: Type 1, one room per floor with domestic accommodation above a shop, and Type 4, multiple warehouses and shops arranged around a courtyard, each with domestic accommodation above, but with a larger purely domestic property forming part of the complex (Schofield and Vince 1994, 73; Grenville 1997, 169). A notable omission from this work was the provision of upper floor plans, which severely limits our understanding of the buildings. The 17th century survey date also makes comparison with earlier typologies less reliable.

More recently, Clarke (2000, 75-79) proposed a typology for medieval shops with three basic types further subdivided by context, features, relationship to other rooms and access connections: (A) single shop units independent of other rooms on the same level; (B) shops connected to rooms behind; and (C) shops connected to rooms at the side. He described type A as being found in high status buildings, occupied by tenants who lived elsewhere, and likened types B and C to Pantin’s right angle type and parallel type respectively. His research suggested that pressure on space in towns prior to the mid-14th century led to the development of two level shops and undercrofts (Clarke 2000, 81). His interpretation is broadly in agreement with those of Pantin and Faulkner, but he drew on a wider range of analytical methods.

Tackley’s Inn

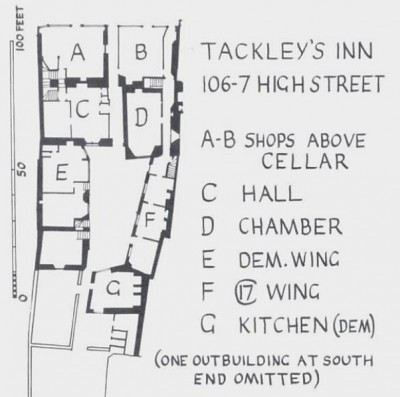

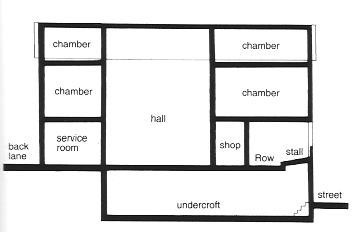

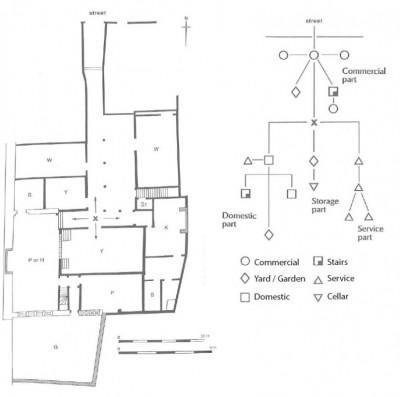

Tackley’s Inn Oxford is a split level shop which has been interpreted a number of times. In his typology, Pantin (1962-63, 219) classified the building as being parallel to the street and having a ‘double-range’ plan. His research indicated that it was built around 1300, and was typical of its type in Oxford (Pantin 1942, 80; 89; 1962-63, 217). It was divided into two parts; the north containing five shops, each with a solar above, and the south containing a hall and chambers for university scholars, accessed by a screened passage between the shops. There was a cellar beneath the north range, and he identified two entrances from the street to the shops and one to the cellar (Pantin 1942, 87). In his work of 1942, Pantin (87) disputed Salter’s earlier suggestion that each of the shops had use of one bay of the cellar, because no evidence had been found to support this. Subsequently, however, he left open this possibility of the cellar being originally divided, confirming only that by 1363 it was being let as a single unit (Pantin 1962-63, 217).

Faulkner argued that archaeological evidence from the standing building indicated the shops were set back from the line of the cellar below, thereby creating a gallery. He also stated that there was only one entrance to street level, that the cellar was not connected to the shops above, and that the domestic accommodation was arranged differently (Faulkner 1967, 127-128).

Munby’s interpretation was based on Buckler’s archaeological recording, undertaken during the demolition of adjacent buildings in 1872-73 (Munby 1979, 123). He concluded that plan evidence from 1814, and the fact the shop range had been rebuilt in the post-medieval period excluded the possibility of a galleried walkway between the shop and street. He also cited the absence of documentary evidence for galleries in Oxford, on the assumption that the building type was typical (Munby 1979, 137). Harris subsequently supported this interpretation (Grenville 1997, 183).

Munby’s and Harris’s work is convincing yet not often cited, and no further interpretations have been made, highlighting the complexity of understanding medieval structures when little fabric or documentary evidence survives. It is possible that the ‘answer’ lies somewhere between Pantin’s and Faulkner’s interpretations – the cellar and access locations as Faulkner’s interpretation and the ground floor arrangement as Pantin’s.

Geographical Approaches

In the medieval period, patterns of land ownership set out the primary property units in towns, which were often subdivided into smaller burgage plots. These were often subdivided by the tenants into smaller plots (Rees Jones 2008, 73-74) and the buildings themselves might also be in multiple occupation (King 2009, 472).

Pearson agreed with Pantin that there are identifiable distribution patterns for his classifications both between and within towns (Pearson 2009, 2). It is accepted that houses near the centre of larger towns had more pressure on space (Pearson 2009, 16; 18; Morrison 2003, 21), so were more likely to have buildings with narrow street frontages and to rise to three or more storeys – the Chester Rows are an example of this. It is thought that jetties originated in towns, being a feature of most shops from 1250 (Clarke 2000, 67; 73; Schofield 1994, 190), and Pearson (2009, 47-48) believes them to be an indication of the pressure on urban space, citing 58 French Street, Southampton as an example which extends considerably over the street. By contrast, houses in smaller towns such as Lavenham were spread out horizontally, with a plan form and construction comparable to rural tripartite houses (Pearson 2009, 20).

Pearson (2009, 1-2) challenged Pantin’s interpretation of the origin of urban house types, claiming it is more likely that the form developed in towns and migrated to rural areas thereafter. She stated that Pantin’s double range plan was a common type of timber framed house in the early 14th century, but significantly only found in large towns (Pearson 2009, 2 & 4), the implication being that it was not an adaptation of a rural type.

Sociological and Historical Approaches

The similarity in housing needs of rural and urban dwellers is another area of debate and Pearson (2004, 43) implied that Pantin had incorrectly assumed they had the same requirements. She stated that urban houses were built without halls from the early 14th century, eventually being omitted from lower to middle class housing by the early 16th century (Pearson 2009, 7). Questioning Pantin’s restricted typology, she suggested that to omit non-hall types and buildings pre-dating 1300, while failing to clarify the impact of the town’s history, its settlement pattern, plot size and the type of people who lived there, on the built form, limited the study’s usefulness in our understanding of the reasons for the various types (Pearson 2004, 43; 2009, 20). Leech also recognized the importance of including both hall and non-hall types in his research as he made a distinction by referring to ‘hallhouses’ as those which had a hall and may or may not have included a shop, and ‘shophouses’ as those without a hall, but which included domestic accommodation over a ground floor shop (Leech 2000, 1).

Quiney (2003, 186) believes that from the 15th century, the favoured form for urban housing was a timber building with an open hall, and that despite not being an efficient use of urban space, it was accepted on the grounds of status. By contrast, Grenville (2008, 122) questioned whether Church ownership of urban properties influenced the form of town houses, such that the desire to increase rental income may have led to omission of the hall. This disparity may reflect differences in ownership or tenancy. Perhaps there was a direct link to the decline of the hall where secular or religious institutions owned speculatively built properties, but the inclusion of a hall persisted where properties were built for occupation by the landlord or higher status tenants (Kermode 1998; Kowaleski 1995 cited in Britnell 2006, 117).

Grenville’s analysis also drew on studies of the social use of space within households, and, possibly in conflict with her comments on ownership, presented a middle ground between the views of Pantin and Pearson. She argued that the identity of urban dwellings was deliberately constructed to be recognisable by rural dwellers, and that this was done because of the migration of rural dwellers to an urban environment (Grenville 2008, 95-104). She proposed that the hall was the mechanism by which social behaviours and family values would be understood, based on evidence that children and young people migrated to towns to work while living in a family home (Grenville 2008, 111-115). In other words, the hall had symbolic meaning that was perhaps more important than its functional use, in both town and country. Goldberg (2008, 136) elaborated further on the impact of young people from the country coming to live and work in urban houses. He suggested that a greater variety and quantity of living accommodation, particularly chambers, was required in order to provide appropriate levels of privacy and separation between family and non-family, male and female. Pearson and Richardson agreed that the pressure on commercial space in the 15th century may have encouraged the use of multi-functional domestic spaces (Richardson 2003, 439), and it is Pearson’s view that the inclusion of private rooms was limited (Pearson 2003, 431).

As regards the non-domestic space, Alston (2004, 40) and Clarke (2000, 59; 63) understand a shop to have been primarily a workshop, based on documentary sources showing that retail activity was not the primary purpose of most medieval shops (Alston 2004, 40-41). Keene (1984, 29) and Schofield (1990, 25) however, believe that there were high street retail shops, side street workshops, and also units where the two uses occurred in one space.

Alston’s study of late medieval workshops in East Anglia used documentary evidence dating to the 15th and 16th centuries to give an indication of the uses of the ‘shop’ space in domestic properties. This indicated that weaving and finishing took place in small workshops, numerous shops contained one or two weaving looms, and weavers worked in their own homes. Alston’s interpretation was that the majority of shops in East Anglian towns were used as cloth workshops (Alston 2004, 39), although a more robust interpretation could be achieved if this was combined with archaeological methods to identify a location within the property. In common with Pearson (2003, 430), who rather bravely suggested that if buildings retain their original fittings that the precise use of the rooms can be determined (Pearson 2003, 430), Alston acknowledges that without full evidence, it is not possible to make a distinction between retail shop and workshop (Alston 2004, 38). It is arguable whether this certainty of use and function would ever be possible, as they relate only to a point in time.

Archaeological Interpretations

Stylistic evidence of architectural features can also be used to inform our understanding of use. Stenning (1985, 35) claimed that the characteristic feature to be used in determining the presence of a shop is the wide, arched top windows, often accompanied by a narrow door with internal shutters. He believes that the narrow door was for the transfer of goods and that there was an intimate relationship between the domestic and commercial parts of the property, with the occupier only entering the shop when a customer was present (Stenning 1985, 35). Clarke (2000, 64) elaborated further on the form of the apertures, stating that this provided a retail shop front for enticing customers as well as lighting the work area, while the narrow door acted as a security measure. He speculated that some trade would be carried out through the window, and that only where increased security was required for the sale of high value goods would the customer enter the shop. Alston (2004, 40-41) conceded that the large windows were a retail advantage, but, on the assumption that the shop was primarily a workshop, interpreted the purpose as lighting. She also believes the narrow doors to be a solution for maximizing space within the shop. Morrison (2003, 24) interpreted the height of the window sill as an indicator of whether customers were served through the window or in the shop.

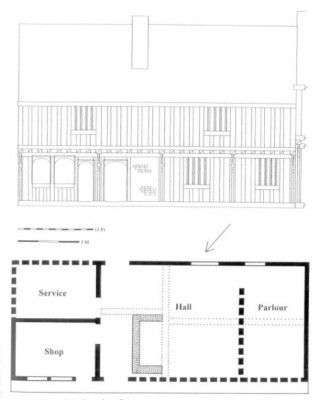

26 Market Place, Lavenham

Dating to the early sixteenth century (Alston 2004, 40), 26 Market Place, Lavenham allows us to consider a number of issues raised in this paper. It has a broad plan similar to the rural tripartite form, and the wide plot, most easily compared to Pantin’s parallel extended plan, is probably a result of there being less competition for street frontage compared to the larger cities (Alston 2004, 43; Pearson 2009, 4). It is two storeys high, with a jettied first floor, displaying the characteristic features of a medieval shop that Stenning (1985, 35) described, and includes evidence for shutters, hinged for use as a counter according to English Heritage (2014) and hinged to the ceiling according to Alston (2004, 40).

From the plan, it is possible to interpret that the shop was run by the occupant of the house because of the direct access between the shop and hall. The presence of a separate door to the hall however, indicates that customers entered the shop space via the narrow door, while seemingly contradictory architectural evidence of low window sills and counters suggests customers were served from the street. Alston (2004, 42) however, interpreted this as a flexible design, allowing the shop to be used by the occupant of the house, or to be let separately as a lock up. The relationship between service area and house is also unclear as its access off the hall indicates it may be domestic but Alston (2004, 42) reported that it was used for storage. Evidence from sketches, wills and inventories generally, confirmed that shops contained shelves, cupboards, benches and storage chests (Morrison 2003, 28) and Alston interpreted the solid panel to the left of the shop windows as possibly concealing the end of internal shelving (Alston 2004, 40).

Questions remain to be answered concerning the function and meaning of the spaces, and it may be that further analysis from sociological or spatial perspectives can aid future interpretations.

Spatial Analysis

Spatial, feature and access analyses were mentioned briefly in relation to Faulkner’s and Clark’s typologies, Grenville’s research and the Lavenham case study. These methods are concerned with the access to rooms, their interconnections, spatial arrangement, function, status and privacy (Fairclough 1992). They are particularly valuable when used in conjunction with other, perhaps more ‘traditional’ methods as Faulkner did in his research of high status medieval buildings (Fairclough 1992, 352). Schofield applied an access diagram to some of the buildings in his typology of London houses from which may be drawn conclusions about privacy and use, and he also demonstrated how a diagram combining use with access can highlight zonal divisions of the space (Schofield 1994). Other methods of analysis include comparison of binary opposites such as public/ private or clean/ dirty to understand the social or cultural associations with a particular type of space (Schofield 1994, 202-203) but this could also be used in reverse, taking accepted associations to determine use, similar to that used in castle studies by Matthieu (1999).

It appears that these methods are not fully explored with enough frequency to be considered mainstream, and it is perhaps through these methods that further understanding will be achieved.

Conclusion

One difficulty with the analysis and interpretation of this building type is that in general, the current research by any scholar is restricted to a specific geographical location, a limited range within the overall type, or a particular period of time; sometimes, all three. This means it is difficult to compare findings and interpretations with great certainty, as what is true of one place at a given time may not hold true of another, or not at the same time.

None of the interpretations have been completely discredited, although there is disagreement on some issues, most notably, the origin of the urban form and the use of commercial space and the hall. The trend has been for scholars to build on the work of those who came before them, and they have demonstrated an increased awareness of the importance of including a wider variation of types. As further research is undertaken, there has been a tendency to draw on a wider range of sources, for example using documentary, stylistic and archaeological methods together, and also incorporating knowledge and methods from other disciplines such as history, geography and sociology. This has contributed to the improved reliability of interpretations, but has also increased the debate. Importantly, it demonstrates how much research is still required not only into the variety of types and forms, but of their uses.

Bibliography

- Alston, L. (2004). Late medieval workshops in East Anglia. In P. S. Barnwell et al. eds. The vernacular workshop : from craft to industry, 1400-1900. York, Council for British Archaeology. 38-59.

- Britnell, R. (2006). Markets, shops, inns, taverns and private houses in medieval English trade. In B. Blondé ed. Buyers & sellers : retail circuits and practices in medieval and early modern Europe. Turnhout: Brepols. 109-123.

- Brown, A ed. (1999). The Rows of Chester. The Chester Rows research project. London: English Heritage.

- Clark, D. (2000). The shop within?: an analysis of the architectural evidence for medieval shops. Architectural History 43 58-87.

- Faulkner, P.A. (1967). Medieval undercrofts and town houses. In P. Faulkner ed. Medieval undercrofts and town houses. London. 118-133.

- Goldberg, P. (2008). The fashioning of bourgeois domesticity in later medieval England: a material culture perspective. In M. Kowaleski and P. J. P. Goldberg eds. Medieval domesticity : home, housing and household in medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 124-144.

- Grenville, J. (1997). Medieval housing. London: Leicester University Press.

- Grenville, J. (2008). Urban and rural houses and households in the late Middle Ages: a case study from Yorkshire. In M. Kowaleski and P.J.P. Goldberg eds. Medieval Domesticity: Home, Housing and Household in medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 92-123.

- King, C. (2009). The interpretation of urban buildings: power, memory and appropriation in Norwich merchants' houses, c. 1400–1660. World Archaeology 41(3) 471-488.

- Leech, R. (2000). The symbolic Hall: historical context and merchant culture in the early modern city. Vernacular Architecture 31 1-10.

- Morrison, K. A. (2003). English shops and shopping: an architectural history. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

- Munby, J. (1979). J.C. Buckler, Tackley's Inn and three medieval houses in Oxford. Oxoniensia 43 123-137.

- Pantin, W. A. (1942). Tackley's Inn, Oxford. Oxoniensia 7 80-93.

- Pantin, W. A. (1962-63). Medieval English town-house plans. Medieval Archaeology 6-7 202-239.

- Pearson, S. (2003). Houses, shops and storage: building evidence from two Kentish ports. In C. Beattie, A. Maslakovic and S. Rees Jones eds. The medieval household in Christian Europe, c. 850-c. 1550: managing power, wealth, and the body / [electronic resource]. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. 409-431.

- Pearson, S. (2004). Rural and urban houses 1100-1500: 'urban adaptation' reconsidered. In K. Giles and C. Dyer eds. Town and country in the middle ages: contrasts, contacts a