They're not exotic ancient axes, nor are they great buildings, but the humble post boxes scattered across our urban and rural landscapes are worth a second look and at least a few moments of reflection. Are they of any archaeological importance or even value? I think so, especially as archaeological evidence and artefacts become ever more contemporary (witness 20th century battlefield sites and Jodrell Bank). Around us we have, in a rather interesting form, clues to the commercial, social, industrial and political practices of the nation, its societies and even its individuals. The boxes still in use today span over 150 years of form, function and design. But of course the postal concept is much more ancient. In the picture above you should just be able to pick out what is a modern roadside box on a pedestal, its users mostly being tourists staying at the hotel or visiting the nearby Roman villa. Taken on the Foss Way in the Cotswolds, which was presumably a vital element of the Roman postal system, the Cursus Publicus, I think the photo can prompt a few thoughts about the passage of private, public and state information, in a reliable and secure manner (or not), over the past 2,000 years.

Visit an important Roman site and you might be presented with some evidence as to how the postal system worked and maybe even examples of the despatches carried. But from the end of the Roman period until relatively modern times there is little physical evidence of postal systems. Clearly volume would have been limited by poor literacy levels but political control of information would have been an equally important constraint. Yet trade and commerce were presumably reliant on at least informal postal systems and there is some evidence that state and ecclesiastical organisations used some form of post boxes and collections in conducting their affairs. Perhaps the earliest in Europe were closed wooden boxes in 16th century churches in Florence used to leave anonymous notes denouncing sinners and traitors. Our oldest box is probably the one shown below in a coaching inn in Spilsby, Lincolnshire, dated to at least 1842 but perhaps as early as 1780. So in artefact terms we are dealing with recent material. However, it is rapidly disappearing but don't let that put you off. Tracking down old or unusual boxes can be as moreish as Pringles or Maltesers and you're always bound to pass a pub.

The Royal Mail was opened to public use by Charles I but it wasn't until Rowland Hill's introduction of the Penny Post in 1840 that volume of mail drove the need for roadside boxes. Too many customers were now rather remote from post offices which were the only place where mail was received. It was Anthony Trollope, then employed as Clerk to the Surveyor of the Western District of the Post Office, who suggested a trial of boxes in the Channel Islands in 1852. (Yes, it was a copy of a French system but our boxes are much superior!) An original is still in use in St Peter Port, Guernsey. The trial was an immediate success and quickly spread to the mainland. Oddly, London was slow on the uptake and the first mainland roadside box was in Carlisle in 1853, followed by Gloucester and then 6 boxes in London in 1855.

The Carlisle square pillar box is long departed and differed markedly to this one (above left) in Dorset dated 1856, made by John M Butt & Co of Gloucester which is the oldest still in use on the mainland. On the right is one of a pair in Framlingham, Suffolk, of the same year made by A Handyside of Derby for the Eastern District. Interestingly, Districts had a lot of autonomy over design and engaging foundries. The first London boxes were not popular (short, square and with notice plates too low to read and often obscured by dirt splashed from the street). Within a year they were gone and replaced by an ornate pillar design, much more pleasing to Victorian aesthetics. A bit like iron mushrooms, the Victorians then saw a range of pillar boxes sprouting until we arrived at the design that most of us are familiar with. Some are:

There is an impressive pair of fluted boxes in Warwick and 3 in Malvern, while Cheltenham still has 8 Penfolds but be careful; the Post Office commissioned replica Penfolds in the 1980s placed in historic sites, including one at Lincoln Cathedral which is clearly an Impostor. Note the lamp on the Rochdale box (real Wallace and Gromit country!) and that the Liverpool Special seems to have an extra lock!

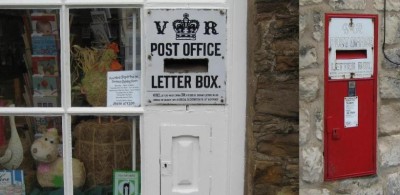

There have, of course, been many other design variations since 1887, while from 1879-87 the Standards were "Anonymous", seemingly an old fashioned cock-up causing the boxes to have no cipher or Post Office markings. VR not amused and there are still quite a few around. Each Sovereign has a unique crown and cipher and it is interesting to see the variations adopted over time, and also between pillar, wall and lamp boxes (the ones attached to posts) as these can vary within individual reigns.

So is this really archaeology or just train spotting? For some it is just an absorbing hobby (for which you don't have to have a tartan thermos and anorak) but our post boxes can give some interesting pointers to the way lives were lived. Who designed the boxes and why were certain styles adopted? The process was really rather muddled, especially for the wall boxes in post offices. Those were not standardised until the 1880s, and until 1895 postmasters installed them at their own expense. (Will this be a problem for Dorcas Lane in Candleford?) An example which has survived due to the insistence of the now retired postmistress at Blancland, Durham, is shown below alongside a Ludlow, the type of box which replaced them. Unlike ordinary wall boxes, the Ludlows have attractive white enamel plates (with stern directions about what may be posted and fines) as well as the collection-time plate. Many Ludlows remain as active boxes though their parent post office may have closed. So here is a useful clue in determining the former use of some buildings. The same can apply to large wall boxes that once served municipal buildings, banks or cooperative societies.

And their important national and economic functions are reflected in box design. Post boxes do possess some latent symbology. They represent order, authority, national cohesion and identity. In Scotland you won't find any boxes with the Queen's cipher in recognition of local sensitivities regarding the title ER II. Contemporary boxes bear only the Scottish crown (below left). It is also interesting that a replica Penfold on the Royal Mile, Edinburgh, (centre) has had the Victorian coat of arms replaced with the Scottish Crown. The political status of the box has seen them bombed in London in 1974 (King's Cross, Picadilly Circus, Victoria Station and Chelsea) and the box on the right is a rare survivor in East Jerusalem from the British Mandate. The colour red has long been an important symbol and boxes in parts of Northern Ireland have often been painted green by republicans; slightly ironic as until 1874 the standard colour was green.

And there's lots more; foundries, designers, short-lived kiosk boxes (8 left, try Whitley Bay) and airmail boxes (probably best to go to Windsor castle), Edward VIII styles and locations which give us some very specific detail on design and distribution in 1936, and general use and abuse (actually they stand abuse very well and perhaps they somehow resist or repel vandalism). A Victorian box in Corporation St, Manchester, was unblemished by the 1996 IRA 3,000 lb truck bomb, though some letters were delayed by a fortnight. What a hero!

Tomorrow's postholes? Think of a tidy line of Victorian pillar boxes along a London thoroughfare; there are some in Kew and Richmond, all serving their various side-streets. The boxes actually go quite deep below the pavement. Now think of areas of cleared Victorian terraces in the East End. Maybe it's stretching the metaphor too far but perhaps future archaeologists will be able to trace what we have lost. Below are two boxes of similar vintage. On the left we have a decaying artefact, a bit like a pot sherd in a trench section. And on the right a nicely preserved piece of Victoriana hardly a dig away from Castle Howard.

Am I alone in finding the tatty one more evocative? Anyway, the good news is that English Heritage and Royal Mail have agreed a policy of retaining all letter boxes in operational service at their existing locations. But the bad news may be that while Charles I opened the Royal Mail to the public it may be in the reign of Charles III that we lose the Post Office. I hope not, and while wishing Her Majesty continued health, I look forward to seeing the first CR III box. (I know where the first ER II pillar box is!). To close, a favourite Lamp Box outside Aberystwyth. If you did get this far I bet you find yourself taking another look.