Just over a century after its destruction by Lucius Mummius, the ancient Greek city of Corinth was re-founded as a Roman colony. Many contemporary sources present this new Corinth as wholly and unswervingly Roman, with no interest in its Greek heritage. However, Corinthian coins dating from the city’s foundation in 44 BCE to 51 CE show a comfortable pairing of Roman and Greek imagery. Local deities appear just as often as Roman emperors, and in many cases they are found on either side of the same coin. This shows that the Corinthian duovir wished to present a new, unique identity that was both Roman and Greek, implying attempts to find simple and clear cultural identities in Roman colonies should be avoided.

In 146 BCE, the Roman commander Lucius Mummius sacked the city of Corinth following its involvement in the Achaean League’s resistance to Roman dominance. More than a century later, in 44 BCE, the city was re-founded as a Roman colony by Julius Caesar, who named it Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis. According to Polybius, Mummius’ soldiers had very little respect for the ancient Greek city’s heritage. ‘I saw with my own eyes pictures thrown on the ground and soldiers played dice on them’ (39.13), notes Polybius1. The new settlers apparently continued the practices of Mummius’ soldiers. Strabo records, for example, that they ‘were removing the ruins’ and ‘digging open the graves’, and as such ‘they left no grave unransacked; so that, well supplied with such things and disposing of them at high price, they filled Rome with Corinthian mortuaries’ (8.6.23). In the 2nd century CE, Pausanias writes that ‘Corinth is no longer inhabited by any of the old Corinthians, but by colonists sent out by the Romans’ (2.1.2) and ‘after Corinth was laid waste by the Romans and the old Corinthians were wiped out, the new settlers broke the custom of offering those sacrifices to the sons of Medea, nor their children cut their hair for them or wear black clothes’ (2.3.7). Thus, according to the ancient authors, the new settlers had very little concern for their city’s past as they sold its artwork and broke religious customs. This image has become an influential view of early Roman Corinth in academia (e.g. Walbank 1997, 107; Barrett 1971, 1-2).

These accounts provide us with an image of new settlers who disassociated themselves from the ancient Greek city, and instead identified themselves as Roman. It appears they were successful in this because even after approximately six generations, Pausanias did not think of the city’s inhabitants as Greeks (2.1.2). Whether we should regard these settlers as Romans or Greeks has been heavily debated. From an ethnographic point of view, the new settlers were mostly freedmen who originated from all over the Roman Empire, but especially from the Greek East (Spawforth 1996; Millis 2010). From a more general point of view, the city had characteristic Roman features such as a consolidated scheme of urban planning, the predominant use of the Latin language, and Roman buildings including the Julian Basilica and the Rostra (Williams 1987). Corinth could thus be regarded as a ‘mini-Rome’ (Aulus Gellius 16.13.9). However, features of the old Greek city were still present, such as the worship of local gods, the remains of Greek buildings, and the Isthmian Games. Surely, there was more than enough ‘Greekness’ for Pausanias to write about when he visited the city in the second century CE.

This paper argues that it is not fruitful to assess the amount of ‘Romanness’ or ‘Greekness’ of the city in order to determine its cultural identity because it was the conjuncture and mediation of both that constituted the identity of the Corinthians (Pawlak 2013). Moreover, drawing sharp distinctions between the two is also problematic because neither are fixed categories or necessarily opposites. Instead, the meaning of the two was dependent on the specific context of employment rather than predetermined definitions (Wallace-Hadrill 1998). In order to determine the identity of the new colony, it is more fruitful to analyze the way the new inhabitants imagined and presented themselves.

Whereas several studies have emphasized Corinth’s connection to its past by focusing, for example, on topography and architecture (Romano 2005), this paper analyses the Corinthian coins from the founding of the Roman colony (44 BCE) until the mid-first century CE (c. 50 CE). It will argue that the colony’s coins explicitly referred to the ancient Greek city. As such, the settlers anchored the Roman colony as the successor of the Greek city. Roman and Greek elements on Corinthian coinage did not conflict with one another; rather, it was precisely their coexistence and interaction that aided Corinth in creating a new political and cultural identity appropriate for a Roman colony within the cultural milieu of the Greek East. Opposed to the dominant view that communities in Roman Greece became Roman while trying to stay Greek (Woolf 1994), the situation in Corinth presents almost the opposite: they tried to become Greek, while staying Roman.

The potential and aim of the colony to develop itself as a political and cultural entity in Greece is apparent from the fact that the city opened an active local mint immediately after its founding. The coins can be used to distill how the magistrates in charge (the duovir) presented their new city. The Corinthian coins have been collected by Michel Amandry in his 1988 monograph as well as in the first volume of the Roman Provincial Coinage (RPC) series (Amandry 1988; Burnett and Amandry 1992).

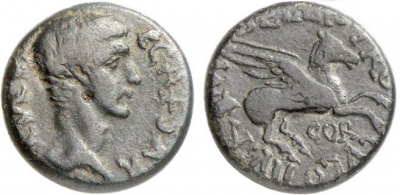

The first issue of the new colony is, in many ways, exemplary to processes mentioned above (Fig. 1). The coins were minted in 44-43 BCE under supervision of the duovir - Aeficius Certus and C. Iulius. On the one hand, the duovir emphasized their connection to Julius Caesar, who founded their colony, through placing his laureate head on the obverse. The reverse, however, indicates that the duovir were familiar with the ancient Greek city and its myths because it depicts Bellerophon mounted on a flying Pegasus, which was one of the most important myths of the ancient Greek city. According to legend, the hero Bellerophon tamed Pegasus with the help of Athena at Corinth. The popularity of the story is widely attested from the 5th century BCE well into the Roman age. The story was specifically connected to Corinth and was not surprisingly a constant in Corinthian pottery and coinage. The size of the coin type, although caution is necessary in combining finds with fixed numbers, seems to have been large: over 123 coins minted between 44-42 BCE have been found.

Christine Thomas has interpreted the appearance of Bellerophon and Pegasus on this first issue as an ‘obvious reference to Roman domination of Greece’ (Thomas 2010, 139). The taming of Pegasus would then be an emulation of how the Romans tamed Greece. However, since the myth had always been present on Corinthian coinage, and would remain so at least until the reign of Septimus Severus (193-211 CE), there is no evidence to suggest that the iconography of the myth would suddenly be differently understood. Neither are there any indications that Rome used myths like this to express their dominance in Greece. Rather, the juxtaposition of the colony’s founder with the old Greek myth on this first issue illustrates how the city presented itself as a new colony, and yet as a continuation of the old Greek city.

Corinthian coinage swiftly followed tendencies in Rome. Corinth was quick to respond with appropriate coin series upon the accession of a new emperor. Moreover, the coins from Corinth show that on multiple occasions the Corinthians went beyond representing the emperor and his wife by putting the portraits of potential successors on their coins. For example, in 2-1 BCE, Gaius and Lucius Caesar (Augustus’ grandsons) were put on the reverse of Corinthian bronzes (RPC I, 1136). The two grandsons of Augustus were additionally honored with statues in the Julian Basilica. Furthermore, on a special issue in 4-5 CE (probably to celebrate the half-century anniversary of the colony), the Corinthians struck alternating heads of Tiberius, Germanicus, Agrippa Postumus, and Drusus Minor, all potential successors in the imperial lineage, on the obverses (RPC I, 1140-1143). In 32-33 CE, the Corinthians even placed Caligula and Tiberius Gemellus, joint-heirs of the emperor Tiberius, on their coins (see Fig. 2). Tiberius Gemellus is hardly represented in our source material because he was quickly removed from the imperial lineage by his joint-heir Caligula. However, in Corinth he appears on coins and even on an inscribed plaque from the Julian Basilica. One of the Corinthian duovir at that time, Publius Vipsanias Agrippa, probably a descendant from a freedman of Marcus Agrippa (Hekster 2015, 124), might have had a special preference for the latter’s line in the imperial lineage as Tiberius Gemellus was in fact the great-grandson of Marcus Agrippa, Publius’ ancestral dominus. In addition, in 37-38 CE, the Corinthians placed Nero and Drusus Caesar (brothers of Caligula) on their coins (RPC I, 1174-1175), and under the reign of Claudius, Nero and Britannicus appear standing face to face on Corinthian bronzes (RPC I, 1182-1184). In conclusion, the range of representations of members of the imperial family in Corinth shows that the city was well-informed; as remarked by Christopher Howgego, the city, being founded by Julius Caesar, remained in some sense ‘under the patronage of the imperial family’ (Howgego 1989, 202). This too was a status which the Corinthians proudly advertised, even occasionally demonstrating local preferences, as we have seen with Tiberius Gemellus.

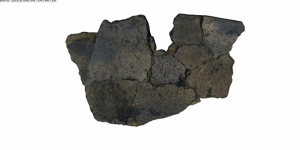

At the same time, the Corinthians used their coins to pay homage to the myths and deities of Corinth, nearly all of whom originated from the ancient Greek city. These included Pegasus, Poseidon, Isthmus, Aphrodite, and Melicertes, the latter being famously connected with the founding of the Isthmian Games, a festival organized by Corinth2. As so many festivities in the ancient world, the Games were initated as funeral games, in this case for Melicertes. His story was well-known in the Greek and Roman world: a young boy whose life was abruptly ended when Hera drove his father to madness and made Ino, the boy’s mother, throw herself down the Molonian cliffs together with her son. A dolphin then carried the dead boy’s body to the Isthmus, where one of the legendary rulers of Corinth, Sisyphus, buried him and initiated the first Isthmian Games in his honor. For this reason, Melicertes often appears with a dolphin on Corinthian coinage: for example, on the reverse of one coin from circa 27 BCE, on which the personification of the Isthmus is placed on the obverse (Fig. 3). Melicertes appeared frequently on Corinthian coinage (Fig. 4), and his Games were considered a fundamental aspect of Corinthian identity. Almost immediately after Corinth’s refounding in 44 BCE, the Games returned to Corinth (Gebhard 1994; Kajava 2002), and a new cult to Melicertes was installed at Isthmia (Gebhard 2005). This shows that the new settlers aimed to establish their city as the legitimate successor of the old Greek city.

Corinth’s coins followed this interest in the local past. During the first ten years of the colony, approximately 62 percent of the coin types referred to the deities mentioned above (80 percent when counting the deities’ attributes, such as dolphins and tridents).With the establishment of the Principate, a great number of coins became understandably devoted to the emperor and his family, as mentioned above and as shown on Fig. 4). Yet even then, the Greek deities appeared frequently on the coins. Approximately 31 percent of all coin types struck between 30 BCE and 51 CE refer to these deities (33 percent when counting the attributes). In addition, these deities were the most prominent to appear on Corinthian coinage. Through their coinage, the duovir thus emphasized their interest in events in Rome as well as Corinthian myths and gods who found their origin in the ancient Greek city.

To conclude, Mary Walbank has drawn a clear distinction between the coins of the 1st and the 2nd century CE, stating that ‘the 1st-century coinage indicates that Corinth was primarily a Roman colony’ and that in the 2nd century ‘Corinth becomes increasingly eager to acknowledge a Classical past (…) in which local cults and myths play a very important part’ (Walbank 2003, 348).

We can now surmise that, although the link to the past might have become a stronger in the 2nd century, Corinth’s interest in its past is already apparent in coinage of the 1st century, on which the city’s most important myths and deities already appeared frequently. Of course, the city presented itself also as a colony founded by Julius Caesar, and subsequently payed homage to the imperial family, as any other city in the Roman Empire. The real problem with Walbank’s statement is the fact that she contemplates the coinage within a framework of dominance of one identity over the other. Instead the conclusion has to be that the duovir chose to present both change and continuity, new and old, Roman and Greek (Howgego 1989), in some cases quite literally as the emperor appeared on the obverse and a reference to one of Corinth’s myths or deities on the reverse. For example, on the large coin type of 37-38 CE, which depicts a bust of Caligula on the obverse and Pegasus on the reverse (Fig. 5). The two sides of the coin should not be seen as contradictory but as complementary to Corinth’s identity, which was tied closely to both Rome and its own past.

Whether or not the Corinthians were successful in establishing this new identity is a different question. The 2nd century orator Favorinus stated that he deserved a statue in the city because ‘though Roman, he has become thoroughly Hellenized, even as your own city has’ (Dio Chrys. 37.26). Yet others addressed the difficulties the Corinthians had in emulating their Greek heritage. Pausanias’ account on Corinth is exemplary in this regard. However, although Pausanias clearly states that he did not think of the Corinthians as true Greeks, his account of the city is extensive and filled with references to the city’s past, which had been kept alive by the new settlers. As a traveller searching for ‘true Greekness’, Pausanias must have had second thoughts after devoting almost his entire second book to Corinth, which he believed to be inhabited by non-Greeks. The emperor Hadrian surely did think of Corinth as truly Greek when he allowed the city to be a member of the Panhellenion, of which an important requirement was the ‘Greekness’ of a city (Spawforth and Walker 1985).

In conclusion, the review of this evidence makes it clear that the Corinthians did not convince everyone of their identity, but one would do well to remember that the city did not aim solely on their Greek past. The city’s coinage striking shows this duality. The city could become Greek, while staying Roman. In the end, the identity of Corinth was imagined and shared by its inhabitants. If we would judge this identity as modern scholars on truth- or falseness, we would follow in the footsteps of Pausanias in search for authenticity. However, in doing so, we would seriously undermine the underlying processes that constituted to the creation of this new identity. Ultimately, the Corinthian identity was not determined by the dominance of one culture over another; rather, it was precisely the coexistence of both a Greek and Roman identity that resulted in a dynamic new Corinthian identity.

Notes

Recent excavations in ancient Corinth have unearthed a significant amount of coins which have not yet been published. Dr Paul Scotton kindly informed me that the finds of the recent excavations do not contrast the results of this paper (personal communication, October 2016).

1All translations of the accounts of the ancient authors are from the Loeb Classical Library. Available at https://www.loebclassics.com/.

2Pegasus: RPC I, 1116-1117, 1127-1128, 1133, 1145, 1147, 1162-1164, 1166, 1169, 1170-1173, 1181, 1224, 1226-1228, 1223, 1235-1237; Edwards 1933, 77-78. Poseidon: RPC I, 1117, 1125-1126, 1137, 1185, 1223, 1225-1226, 1234-1236. Isthmus: RPC I, 1164, 1167-1169; Edwards 1933, 79. Aphrodite: RPC I, 1127-1128. Melicertes: RPC I, 1162, 1165, 1168, 1170, 1186-1188; Edwards 1933, 77-79.

Bibliography

- Amandry, M. (1988). Le monnayage des duovirs Corinthiens. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique Supplément. 15. Paris: De Boccard.

- Barrett, C. (1971). The first epistle to the Corinthians. London: Hendrickson.

- Burnett, A. and Amandry M. (1992). Roman provincial coinage: volume I: from the death of Caesar to the death of Vitellius (44 BC-AD 69). London: British Museum Press.

- Edwards, K. (1933). Coins, 1896-1929. Corinth: Results of Excavations conducted by The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 6. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gebhard, E. (1994). The Isthmian Games and the sanctuary of Poseidon in the Early empire. In T. Gregory (Ed). The Corinthia in the Roman period. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series. 8. Ann Arbor: Cushing-Malloy Inc. 78-94.

- Gebhard, E. (2005). Rites for Melikertes-Palaimon in Early Roman Corinth. In D. Schowalter and S. Friesen (Eds). Urban religion in Roman Corinth: interdisciplinary approaches. Harvard Theological Studies. 53. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 165-203.

- Hekster, O. (2015). Emperors and ancestors: Roman rulers and the constraints of tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howgego, C. (1989). After the colt has bolted: a review of Amandry on Roman Corinth. The Numismatic Chronicle. 149, 109-208.

- Kajava, M. (2002). When did the Isthmian Games return to the Isthmus? (Rereading “Corinth” 8.3.153). Classical Philology. 97 (2), 168-178.

- Millis, B. (2010). The social and ethnic origins of the colonists in Early Roman Corinth. In S. Friesen, D. Schowalter, and J. Walters (Eds). Corinth in context: comparative studies on religion and society. Leiden; Boston: Brill. 13-36.

- Pawlak, M. (2013). Corinth after 44 BC: ethnical and cultural changes. Electrum. 20, 143-162.

- Romano, D. (2005). Urban and rural planning in Roman Corinth. In D. Schowalter and S. Friesen (Eds). Urban religion in Roman Corinth: interdisciplinary approaches. Harvard Theological Studies. 53. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 25-59.

- Spawforth, A. (1996). Roman Corinth: the formation of a colonial elite. In A. Rizakis (Ed). Roman onomastics in the Greek East: social and political aspects. Proceedings of the international colloquium on Roman onomastics, Athens, 7-9 September 1993. Meletemata. 21. Athens: Research Center for Greek and Roman Antiquity. 167-182.

- Spawforth, A. and Walker, S. (1985). The world of the Panhellenion. I. Athens and Eleusis. The Journal of Roman Studies. 75, 78-104.

- Walbank, M. (1997). The foundation and planning of Early Roman Corinth. The Journal of Roman Archaeology. 10, 95-130.

- Wallace-Hadrill, A. (1998). To be Roman, go Greek. Thoughts on Hellenization at Rome. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 42 (72), 79-91.

- Williams, C. (1987). The refounding of Corinth: some Roman religious attitudes. In S. Macready and F. Thompson (Eds). Roman architecture in the Greek world. The Society of Antiquaries of London: Occasional Papers (New Series). 10. London: Society of Antiquaries of London. 26-37.

- Woolf, G. (1994). Becoming Roman staying Greek: culture, identity and the civilizing process in the Roman East. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society. 40, 116-143

|

|