Careful study of different sites can help to create approaches towards heritage management for the future. Heritage management in Cambodia, specifically the site of Banteay Chhmar, is one case study useful for approaching the application of different conservation models, such as the Living Heritage Approach, which is not well facilitated in Cambodia. This paper will discuss heritage management and conservation in Cambodia. The site of Banteay Chhmar will be explored as a case study in order to examine the successes and problems of the approaches used with a focus on the application of a Living Heritage Approach. It is important to note that each approach has its own successes and failures, and that current heritage management strategies need to be constantly reevaluated. Measuring the successes and failures of any heritage management strategy needs to be done within the context of the site and the values that it holds for the population involved in the management.

The nation of Cambodia has a rich cultural heritage from the monumental temple sites of the Angkorian Empire to the stylized forms of Khmer traditional ballet, but heritage management is still problematic in this developing country. Cambodia serves as an excellent example of how heritage is managed in a developing country that combines top-down Western models with the Living Heritage Approach at certain sites. Heritage site management was shaped by outsiders from the École Française d'Extrême Orient to UNESCO and APSARA (World Archaeology 2011). As a result, most sites have been managed primarily with top-down strategies set out by these organizations, disregarding the involvement of the local population and the fact that people have been living continuously on many sites.

This is particularly true at the site of Angkor where local heritage police have almost completely driven out the indigenous population for the sake of site preservation (Miura 2005; Fletcher 2007). Angkor itself was never completely abandoned, and people have lived there from its construction through the present with still inhabited villages within the complex (Fletcher 2007). The site management strategies at the Angkor complex serve as a cautionary tale for the failings of overzealous top-down Western-value-centric approaches (Miura 2005, 3). Many of the heritage management approaches at Angkor, and throughout the country, ignore the potential for using the Living Heritage Approach as a conservation tool. This is largely due to the fact that organizations like APSARA, UNESCO, and the Global Heritage Fund have great influence in a country that has very little funding for heritage management (Miura 2005). These large institutions have had their ideological foundations shaped by the Authorized Heritage Discourse. This greatly affects how heritage is managed in Cambodia.

Banteay Chhmar

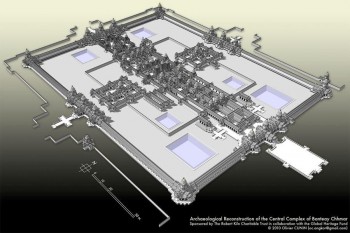

Translated as “Citadel of Cats,” this site in northwest Cambodia contains the fourth largest temple of the Angkorian Empire (World Archaeology 2011). It was built by Jayavarman in the 12th century CE and is described as, “a one-kilometer arcaded enclosure wall…carved with detailed bas-reliefs telling the story of the Ancient Khmer, depicting royal processions and battles, and festooned with multiple, exquisitely detailed images of the multi-armed boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara,” (Global Heritage Fund 2019, see Figure 1). The similarities between Banteay Chhmar and temples like Bayon and Angkor Thom in Angkor indicate that Banteay Chhmar was a prototype for the construction of Angkor. Architectural styles, bas-relief carvings, and sculptural styles at Banteay Chhmar are repeated throughout other temples later built in Angkor by Jayavarman the 7th century CE (World Archaeology 2011).

Tragically, many of the bas-reliefs that decorate the temple walls have been removed by looters, which has seen a large number of artefacts disappear across the Thai border (Pech 2017, Regg-Cohen 2003). The Cambodian government has also removed some of the bas-reliefs and placed them on display in the National Museum in Phnom Penh (Pech 2017. Banteay Chhmar has been on the top of the list of nominations for World Heritage Site status since 1992, but it has yet to receive the protection it needs. There are also several local villages that make up the Banteay Chhmar Commune in what is described as glorious isolation (Tham 2019). Similarly to the Angkor complex, this site was never wholly abandoned by the local population who have lived near or on the site since its construction. In other words, Banteay Chhmar has always simultaneously been an occupied site as well as a heritage site. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Conservation Strategies

The largest group involved with the conservation at Banteay Chhmar is the Global Heritage Fund, GHF, who advocate a holistic 360-degree approach by design wherein they attempt to integrate the values of large and small scale groups in order to develop sustainable practices (Olson 2019; Global Heritage Fund 2019). The Global Heritage Fund uses a Living Heritage Approach to create a conservation project that integrates the needs of over eighty stakeholder groups. Some of the ways this is done is through homestays in the local villages (Figure 2), cooking classes, silk weaving, and traditional village celebrations in which visitors can participate (Visit Banteay Chhmar 2019). These activities are facilitated by the locals. The Living Heritage Approach attempts to engage the people living near Banteay Chhmar to become part of the life of the site. The formation of locally-driven organizations such as the South Asian Conservation, Restoration Agency, and Banteay Chhmar Community-Based Tourism all work on site management. These groups have also been highly successful (Olson 2019; Pawson 2016). The groups have been successful, in fact, that the local communities have won awards from the national government for their achievements (Olson 2019).

However, there is still a top-down model in place for the conservation and management of Banteay Chhmar in which large multi-national groups like Global Heritage Fund bring in professionals to work on the buildings. Led by John Sanday, these conservationists have been responsible for most of the restoration work on site, such as the restoration of sandstone bas-reliefs, training of local teams to carry on the work, and anastylosis of the southeastern gallery (Strebe 2017). It is important to highlight that many of these professionals were trained using Western notions of what heritage is and view Banteay Chhmar through that perspective (Pawson 2016). This would undoubtedly colour the strategies they use, their perspective on heritage management, and what they teach to the local teams. Even though the site was turned over to Cambodia government control in 2015, a core group of highly trained laborers have continued to lend their expertise to restorations on the site, which will further perpetuate Western models of heritage management (Strebe 2017).

Successes

The holistic integration of different approaches in Banteay Chhmar has been widely successful in addressing the values of the stakeholders concerned. There have been both economic and educational gains for the local community, which encourages their active participation. The local community now views itself as caretakers of the local heritage and understands the effectiveness of the site management (Pawson 2016). Local people are being trained as conservators, tour guides, and teachers, amongst others. Community members have set up their own tourism organization to ensure that they maintain local control over the tourist industry. The Banteay Chhmar Community-Based Tourism has a transparent organizational structure that encourages the participation of the villagers in site management (Pawson 2016). There has been good decision-making and planning that attempts to integrate all the needs of the stakeholders, and it appears that all aspects are as well integrated as possible in heritage management. Most of the successes of this approach can be measured quantifiably. For example, visitor numbers at Banteay Chhmar have increased over one-hundred percent since 2016, and these higher visitor numbers have increased the income of villagers (Tham 2019).

Problems

As successful as this approach has been, there are still issues. For example, the major source of problems is the lack of regional infrastructure. In this province, roadways are poorly maintained, creating accessibility problems for potential visitors. Another concern is the sustainability of establishing an economy dependent on tourist dollars. Currently, most of the funding for the site comes from the GHF and other outside organizations. The majority of local villagers rely on farming as their main income. If they shift over to tourism as their main income, this lack of sustainability could potentially wreak economic havoc if tourism dries up. Without World Heritage status, getting the funding to develop infrastructure and sustainability is going to be a constant problem. Since most of the time and attention of the Cambodian government goes towards Angkor Wat and its environs, getting World Heritage status for this site has been pushed to the back burner (Miura 2005). The lack of infrastructure also effects the security of the site with looting so prolific that some of the bas-reliefs have been taken to the national museum for their own protection (Regg-Cohen 2003). Further looting and damage could devastate the site and permanently damage the historical and cultural value of Banteay Chhmar.

The site of Banteay Chhamr serves as an excellent case study for the state of heritage management in Cambodia. It also serves as an example of the success and problems of using the Living Heritage Approach in Cambodia. In conclusion, the influence of Western-centric thought, informed by the authorized heritage discourse, is evident at Banteay Chhmar, especially in terms of defining heritage. In this case, it is the monumental architecture of the temple site that is being conserved, with the penultimate goal of UNESCO World Heritage Status. Stakeholders involved are still using the paradigms shaped by the Authorized Heritage Discourse, and less attention is being paid to the intangible cultural heritage. These problems need to be addressed for future site management. If they can be solved, Banteay Chhmar could serve as a model for the holistic integration of values for heritage site management moving forward.

References

Angel, K. (2010) The Backstory: The Perils Of Popularity. Condé Nast's Traveler, (7), 38.

Fletcher, R., Johnson, I., Bruce, E., and Khun-Neay, K. (2007). Living with Heritage: Site Monitoring and Heritage Values in Greater Angkor and the Angkor World Heritage Site, Cambodia. World Archaeology, 39 (3), 385-405.

Global Heritage Fund (2019). Banteay Chhmar, Cambodia . [Online], Global Heritage Fund. Available at: https://globalheritagefund.org/what-we-do/projects-and-programs/banteay-... Accessed on: 4 March 2019.

Miura, K. (2005). Conservation of a ‘Living Heritage Site’ A Contradiction in Terms? A Case Study of Angkor World Heritage Site. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 7 (1), 3-18.

Olson, E. (2019). GHF-Supported Community Based Tourism (CBT) Organization Receives Top Award from Cambodian Government. [Online] Global Heritage Fund. Available at: https://globalheritagefund.org/2019/01/22/ghf-supported-community-based-... Accessed on: 4 March 2019.

O’Reilly, D. (2014). Heritage and Development: Lessons from Cambodia. Public Archaeology, 13 (1-3), 200-212.

Pawson, S., D'Arcy, P., and Richardson, S. (2016). The Value of Community-Based Tourism in Banteay Chhmar, Cambodia. Tourism Geographies, 19 (3), 378-397.

Pech, S. (2017). Bid to Have More Heritage Sites. [Online] Khmer Times. Available at: https://www.khmertimeskh.com/12017/bid-to-have-more-heritage-sites/ Accessed on: 1 March 2019.

Regg-Cohen, M. (2003). Raiders of Angkor Wat's Relics; Thieves, Tourists Top List of Dangers to Khmer Culture Corruption Also Killing 'Goose that Lays Golden Egg'. [Online] Toronto Star p.F05. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/438614510?accountid=14511 Accessed on: 4 March 2019.

Strebe, M. (2017). GHF Staff Visit Banteay Chhmar, Monitor Ongoing. [Online] Global Heritage Fund. Available at: https://globalheritagefund.org/2017/04/18/ghf-staff-visit-banteay-chhmar... Accessed on: 2 March 2019.

Tham, D. (2019). Banteay Chhmar temple: Angkor Wat Without the Crowds?. [Online] CNN Travel. Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/cambodia-temple-banteay-chhmar/ind... Accessed on: 1 March 2019.

Visit Banteay Chhmar. (2019). Visit Banteay Chhmar. [online] Visit Banteay Chhmar. Available at: https://www.visitbanteaychhmar.org/ Accessed on: 4 March 2019.

World Archaeology. (2011). Banteay Chhmar. [Online] World Archaeology. Available at: https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/saving-banteay-chhmar/ Accessed on: 4 March 2019.