Archaeological techniques have drastically changed in recent history. Rather than excavating in order to find evidence to fit a particular narrative, the preference to uncover the evidence first and then explain the most likely outcome has become a much more solid basis for argument. For example, there was a long-held belief that there lay a church east of the 12th century St. Mary’s Church in Oakwellgate, Gateshead. This has since been disproved in a recent excavation as no evidence was found to support Roman occupation (Nolan & Vaughan, 2007 p.128). Another issue with previous archaeological excavations and reports is that they were carried out with what would now be referred to as outdated methods. Techniques have improved; radio carbon dating from the middle of the 20th century (Greene & Moore, 2010 p.167) and in general, more refined processes has allowed more precise dating and preservation of artefacts. Previous excavation sites have since been given additional interpretations (Cosh, 2004 pp.229-233).

The evidence of churches may also be detailed in various literary sources such as Bede and inscriptions. However, while a church may have existed there must be archaeological evidence to support other sources. For example, a chi-rho symbol does not simply suggest that there was a church at that location (Mattingly, 2006 pp.466-467). The issue with documenting the decline of paganism and the rise of Christianity in Britain is the scarcity of material in the fourth century (ibid, 325); which was at the time when Christianity began to truly popularise. I will argue that the archaeological record suggests that churches were not at all widespread in Britain. The significant distance away from Rome and the hub of Christianity may have meant that Britain was less influenced by the central provinces, meaning that imperial law was less potent in Britain. On the contrary in Rome, the aristocracy and dominance of pagan worship may have meant that it took much longer than the provinces to ‘Christianise’. The outlawing of pagan temples in 341, as Mattingly argues, does not have such a direct and abrupt impact in Britain (ibid, 348); it seems that it took much longer on the periphery to adopt state law. While this does not mean that the temples were converted to Christian churches immediately, it does suggest that the evidence can be contradictory as pagan material left behind during a conversion may make it harder to distinguish between churches and pagan temples. While also examining the evidence for churches in Roman Britain, I will argue that the mere presence of the surviving foundations is not adequate information for the assumption that the building in question was a Christian place of worship. The end of Roman power or when Britain was no longer subjected to Roman law is debated, but the date of 409CE will be used (ibid, 529).

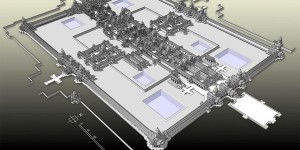

With the aim to treat Christians benevolently in the Empire, the Edict of Milan in 313 allowed Christians to build larger places of worship. At the centre of most Roman towns was the basilica which eventually, but not with immediate effect, became attributed to Christianity (Petts, 2003, pp.54-55). Villas also had apses and basilicas which makes the issue of determining whether or not the structure was a church even more problematic (Witts, 2000 p.296). Other features include a semi-circular apse, which was common in church construction. This type of construction however was also common in temples, such as those of the cult of Mithras. Although they are common features of churches, the apse does not denote that the building was a place of worship. An apse may mean that it was the focal point of the room. Another feature of churches was that, during the late fourth-century to the end of the eighth, churches had the entrance to the east and their sanctuary occidental (Coomans, 2018 p.28). If a structure is dated to before the Edict of Milan in 313, it becomes unlikely that it was built as a church simply because it would have been illegal. The Edict of Thessalonica in 380 made Christianity state religion in the empire, and so from both of these edicts Christians became more prominent. During the late Roman Empire and beyond, intermittent persecutions of both Christians and pagans occurred. It is possible that people were pretending to be Christian while actually still being polytheistic, or vice-versa; the existence of dual-use houses does still mean there was indeed a church present.

The evidence for a church at Verulamium (St. Albans) is debatable. Britain’s first Christian martyr, Saint Alban, lived in the Roman town and thus it is easy to attribute religious structures to the area. Niblett, largely building on Mortimer Wheeler’s outdated work, states that “there is an absence of fifth and sixth-century Saxon cemeteries within 30km of St Albans” (Niblett, 2010a p.129), perhaps suggesting that Verulamium itself was the site of a church. Bede, writing in the eighth century, also notes that there was a church here (Bede, 1999). In Verulamium The Roman City of St Albans (2010b), also by Rosalind Niblett, she suggests that there could be up to three possible locations that may have once been used as a church; the sites are Insula XVI, Insula XI and Verulam Hill (Excavated in 1934, 1937 and 1966 respectively).

In general, any building during its lifetime could change purpose, become renovated, derelict or abandoned and thus it difficult to determine that a building was used as a church. Some key indicators are the location, the outline of the structure itself and more importantly, other material found at the site. As Niblett notes, “portable items with Christian symbols are completely absent from the town [of Verulamium]” (Niblett, 2010b pp.136-137). Unfortunately, the excavations at Insula XVI were incomprehensive and failed to surmount to any significant conclusions. The basis that the other the structures could be a church rested solely on their structural plans; Verulam Hill had a semi-circular apse and the identification that is a church rest on this. It is also possible that the Abbey today at St. Albans was built upon a previous Roman church. The fragmented ‘basilica inscription’ (RIB 3123. See also RIB 222, 226-229) notes that there was a probably a basilica at the centre of the town and while this could be interpreted to mean that there was a church present, as this type of architecture became common in the construction of churches. However, this is just hypothetical as there is no concrete archaeological evidence to support this claim. Petts concurs, stating that the likelihood that the structure was a church is small (Petts, 2003 p.62).

Three British bishops from London, York and Lincoln or Colchester are mentioned at the Council of Arles in 314 suggests that there should be places of worship at these locations; each bishop had an ecclesiastical province with allegiance to the See of Rome. Excavations under the current building at St. Paul-in-the-Bail, Lincoln have indicated that there was a previous building made of timber which could have also been a church as it is of Roman date (Mattingly, 2006 p.348 & Petts, 2003 p.17). Despite this, there is no direct evidence such as Christian paintings or objects, to definitively determine that the building was a church. Butt Road, Colchester is another claim for a church. David Walsh, applying an in-depth analysis with the available evidence, concludes that there is uncertainty regarding the church hypothesis because the adjacent cemetery cannot be characterised as Christian, and the date of the construction could fall between 290 and 310 CE as between 320 and 330 CE (Walsh, 2018 p.367). Walsh also argues that it is much more likely that the Butt Road building could have actually served as a mithraeum, as part of the Cult of Mithras. Future excavations may yield more conclusive results.

More satisfactory evidence of rural churches, as argued by David Petts (2003), can be seen at the site of Icklingham. As with many structures throughout history, the building may have been reused for another purpose during its life; Petts argues that the site may have been predated by a pagan temple (Petts, 2003 p.69). As Paganism declined and Christianity rose after the Edict of Milan, the building could have become a Christian shrine. There have been a number of Christian items uncovered around the site (Mattingly, 2006 p.487), and so it is probable that the site here was used by Christian devotees as a small place of worship.

Was the villa at Hinton St. Mary, Dorset a house church? The villa here is dated to the late third century at the earliest, meaning that is was built before the Edict of Milan in 313, but the building could have changed purpose (ibid, 400). House churches were used as they were of much lower cost than purpose-built churches; it was easier for the local people to congregate. House churches were also suited for a smaller group of people, as a church would perhaps not be required if there are only a small group of people practicing Christianity in their local area (Filson, 1939 p.106). When the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (272-337) issued the toleration for Christians, they began to move to larger buildings. The question of whether the villa was a church rests on the person depicted in the mosaic. Again, the evidence is not concrete due to various reasons. Traditionally, because of the chi-rho symbol and the similarities with other depictions of Christ, the mosaic is assumed to be him (Painter, 1967). Pearce has suggested that this could be an emperor from the House of Constantine (Pearce, 2008 p.214). One would assume that because the mosaic features Christian iconography then the place where it was kept would have been an altar, shrine or house-church for the worship of Christianity. Additionally, she suggests that one of the ways to be Christian during the fourth century was by allegiance to the imperial house of Constantine (ibid, 214). While it cannot be said for certain if this villa was a house-church as the material found is inconclusive and no other Christian material was found. However, pagan mosaics were found, suggesting dual use (Mattingly, 2006 p.467).

The Lullingstone villa has remarkable similarities to the Hinton St Mary villa in Dorset. Painter states that “[it] is certain that the paintings demonstrate that the owners of the house were Christian and of considerable wealth and piety” (Painter 1969, p.143), and it seems that the conclusion has not changed since. Mattingly argues that the Lullingstone villa incorporated a room which was converted to a Christian chapel (Mattingly, 2006 p.467). The building is also room to various pagan iconography, suggesting dual use like the Hinton villa.

At face value, the site at Silchester looks to be a church, and has been argued that it is (Walter, 1912 p.212). Petts contends that “identification of this site is ultimately subjective” (Petts, 2003 p.57-59). A semi-circular apse to the west of the building, a nave paved with red cubes and a font base was found close to the entrance at the east. These all point to a church. Indeed, these features are common of ecclesiastical architecture. In contradiction, the building pre-dates the Edict of Milan; Cosh dates the building to the late second-century, which of course has “implications for the identification of the building’s original function” (Cosh, 2004 p.233). Furthermore, no Christian iconography was found at the excavation site and the very location of the structure, at the edge of town, further supports the indication that the building was not a church. But other than a church, there are few other alternatives. The most likely alternative, based upon the size and shape, is that it was a collegium; a meeting place for the officials of the town. Ultimately the evidence is contentious, and a conclusion cannot be reached. To add insult to injury, the excavation methods in the nineteenth-century disturbed the site, making dating more difficult (Petts, 2003 p.60).

There is no significant evidence to prove that there were churches at Hadrian’s wall. The Roman fort of Houseteads is a possible location, argued by Crow (1995, 96-97). Irby-Massie argues that there is little to suggest that there was a strong Christian presence among the military in the late-Roman empire (Irby-Massie, 1999 p.194). I am inclined to agree with this statement; while some of them may have been followers, there is little evidence apart from slightly suggestive tombstones such as RIB 1812 or RIB 690 and a coin purse (Collins, 2008 p.2), which is not evocative of a strong following or a Church.

Other sites to consider are Richborough (Kent), Vindolanda and Canterbury. The Richborough excavations in 1923 were subject to poor techniques; the top-soil was not given attention as was the standard at the time (Petts, 2003 p.75). The structure was west-east aligned but there was little additional information for corroboration. The Roman area of Vindolanda causes debate. Petts argues that is the “best candidate” for a church at Hadrian’s Wall but the evidence is inconclusive. The argued church area dated to around 400CE, has a good location with an has an apse. But none of these factors definitively point to a church. The alleged oldest church in England was built upon a previous Roman structure in Canterbury, however it is uncertain that previous building was used as a church (Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society, 2015. See also Irby-Massie, 1999 p.198, note 72).

Taking into consideration archaeological evidence, it can be argued that the claims for churches in Roman Britain are unconvincing. The worship of Christianity seems to be concentrated in the south and south-east of Britain in the late Roman Empire. If we consider the etymology and history of the name of St. Albans, the claim that there was a church here makes sense; the current cathedral probably covers the original site if one exists at all. The most likely public (not house-churches) sites such as Butts Road, Icklingham and St. Paul-in-the-Bail are still disputable claims. The Hinton St. Mary and Lullingstone villas are the most likely candidates for dual use house-churches. This also suggests that there is fluidity between pagan and Christian worship. Some of the cases mentioned such as Silchester may have been proved or disproved if the methods at the time of excavation were that of the standards of today. The evidence is the strongest in relation to villas, suggesting that Christianity is prominent among the higher classes. Most of the candidates have the same conclusion: possibly, but not certainly a Christian Church.