As an archaeology student, you learn to look at life from a different perspective. Though my personal interest lies within the distant past, recent developments have led me to apply my archaeological training on my own past. As a foreign student living in York, the connection to what is happening in my native country, the Netherlands, isn’t what it used to be, due to how busy student life is. However, that changed recently when the UN allegedly declared that they would start an investigation into ‘Zwarte Piet’ (Black Pete) (ANP a & b, 2013), Saint Nicholas’ companion in the Dutch tradition of Sinterklaas, celebrated on the 5th of December, as they had received racism complaints from people living in the Netherlands. I started researching the issue and reading international newspapers or even UK news stories, which enraged me, even more. Below you will find the real explanation as to what this ‘Sinterklaas’ celebration is, the history behind the man, a brief evaluation of the tradition’s history, a look into the origins of Black Pete, the problems that have been surfacing in the Netherlands for at least a decade now, and finally Sinterklaas’ connection to Santa Claus.

Sinterklaas, as he is known in the Netherlands and Belgium, is no stranger to other parts of Western Europe, with French and Germanic counterparts. But who is this man, and who are his companions? Where does the tradition come from, and what connection is there with Santa Claus? Originally I thought that it would be a difficult task, trying to gather information without having access to a Dutch library, but I found out I was heavily mistaken.

What is 'Sinterklaas'?

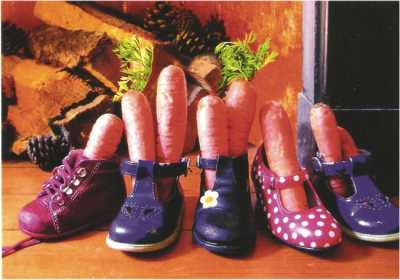

Every year at the end of November there is a big parade aired on national television, so that all children can experience the arrival of the Saint and all his Petes into the country via his steamboat from Spain. During their time in the Netherlands, they will gather information on all the children, whether they have been good or bad, and write their findings in the Saint’s big book. The old tales tell of Black Pete putting the naughty children in his big bag, in which he normally carries the presents, to take them back to Spain for punishment. During the time that he is in the country, children can experience him in several ways. At home, one shoe is left in a room other than the bedroom, preferably near a fireplace, radiator or window. The story states that the Saint and his Petes will walk on all the roofs to gather their information. In order to be kind, the children will leave glasses of water and carrots, for the Saint's horse, and drawings, so the Saint and his Petes can take a break, and leave some sweets (Figure 2).

Another way is to have him visit schools, clubs or any other kind of social gathering. Here, the children will be in one big space when the Saint and the Petes enter; all of them get candy, and are one by one called forward to the Saint. He then reads from his book and tells the child when he or she has done well in the last year and when they’ve been naughty (this list is provided by the organisers of the event). After this, the child is given a small present. There are also private house visits.

When the children reach the age at which they know he doesn’t really exist, the visits and the mysterious gifts are replaced with a ‘surprise’ evening (using the French pronunciation sur-pri-se), similar to Secret Santa, the only difference being that the presents are bestowed in a specially crafted fashion representing the receiver of the gift, including a unique poem describing the receiver and the gifts. This normally takes place on the fifth of December.

As a young child, I watched the big parade, put out my shoe and partook in the school and home celebrations, and the surprise evenings. I was even lucky enough to be a Black Pete myself for one weekend. In general the Saint is regarded as a very wise, old and kind man. Black Pete however, is regarded as a bit of a clown, but also as quite scary, for it is he who punishes the naughty children (it is not a real punishment, more of a threat that is spread).

This special time of year doesn’t just see the Saint and his Petes arrive. Long before they even enter the country, special sweets reach the shops: chocolate letters, good as shoe presents, 'schuimpjes' and all kinds of 'speculaas', pepernoten, chocolate money, and different kinds of marzipan. (My apologies to all non-Dutch speakers, but most of the names of these sweets have no English equivalent.) These are the things I look forward to most now, but the child inside me still puts out her shoe!

Who is Sinterklaas?

Sinterklaas is based upon Saint Nicholas, who was a bishop in 4th century Myra, modern-day Turkey (Anon n.d.); he was known for his generosity and kindness to poor people and children. Saint Nicolas became a patron saint for sailors and small businesses across Europe as his story spread. Unfortunately there are not many sources available regarding when the people in North-West Europe started the tradition, although all the sources seem to agree that it was sometime in the Middle Ages (Boer-Dirks 1993).

While researching the history behind the festive traditions, I have only been able to find one source that looks into the history of both characters in such a way that sheds some light on it.

Boer-Dirks (1993) indicates that the precise beginning of these traditions is unknown. The first mention of them dates to the 14th century. The main source of information comes from manuscripts. A manuscript from 1470 has the oldest known image of Saint Nicholas, and a manuscript from 1498 shows the Saint with three boys. However, no mention of a companion is made for centuries to come.

One of the difficulties of researching the tradition is due to the reformation, which caused a lot of upheaval in the Netherlands and the destruction of large amounts of source material. However, evidence of these traditions remains today, including complaints from people not agreeing with the fact that a festive family day is celebrated on a Catholic Saint's day. These complaints now serve as very precious firsthand accounts into the celebrations of that time. One source, a pastor from Gouda in 1658, gives a detailed account of the practices in the Dutch houses on the evening in question. The pastor mentions the Saint, and how it is wrong to deceive the children like this, however no mention is made of a companion (Boer-Dirks 1993).

The in-depth research into the origins of Sinterklaas begins in the 19th century. Although it was known that the Saint was based on an actual living person from the 4th century, the deeper meaning was sought by some in the pagan past. German researchers explained the festivities as being related to pagan celebrations of the god Wodan. One of the Grimm brothers placed the origin of both Saint and companion in the pre-Catholic times of the north, as with the arrival of Christianity, the pagan feasts were outlawed and in this way, the people were still able to hold on to their own traditions. This would explain the sometimes scary appearance of Black Pete, as the Saint would represent Wodan, and Pete one of his cronies. Sources dating from the same period, but from the Netherlands, also follow this path, though hardly mentioning Black Pete (Boer-Dirks 1993).

The responses from Catholic sources that come forward to the research mentioned above, are not pleasant, claiming that he is a representation of the devil. The evidence that this is based on is rather thin; they say that there are some surviving images of the saint with a chained devil at his feet, and this devil is black. However this depiction is not just reserved for Saint Nicholas, but was used several times in the Netherlands' medieval past with both white and black devils, and doesn’t continue on in more recent history (Boer-Dirks 1993).

A more recent explanation for the Saint’s companion claims that Black Pete is one of the African child slaves he has rescued during his life (Scheer 2013). On the other hand, one would be inclined to think that if that should be the case, it should have been mentioned in earlier sources, or even within the research conducted by Boer-Dirks (1993).

Could the final explanation just be a contemporary answer in a racial sensitive matter? Another contemporary story is that Black Pete is black due to the fact he spends most of his time going up and down chimneys, so that essentially he could be of any race or colour, but is so dirty that it is not visible. This last explanation sounds more like an excuse than anything else.

None of the reasons mentioned above explain the presence or appearance of Black Pete. Boer-Dirks (1993) comes closest when she discusses the earliest mention of Black Pete arising in the late first half of the 19th century. These days it is normal that the Saint makes a house-visit, but in the sources there is no mention of this, nor in the paintings or images that are produced. The earliest mention of this dates from 1831, but later researchers do not mention it, which results in Boer-Dirks (1993) concluding that the house-visits began in the first half of the 19th century. These home-visits almost go parallel with the first explicit mention of Black Pete. The earliest depiction of Black Pete is that of a brown boy in 16th century Spanish costume, although he originally remained nameless for quite some time. From the second half of the 19th century, the Saint’s companion becomes a standard part of the imagery and by the end of the century he even has the name Pete. Boer-Dirks (1993) believes that is due to the invention of the house-visits – the Saint is depicted as an affluent man, who in those times had servants. The first depiction of Black Pete is therefore as a groomsman. The origins of Black Pete coming into play have to be considered. As far as I am aware, slaves were never a part of society in the Netherlands, not taking Roman times into consideration. There were many different layers in society, but personally I have never heard the word slave mentioned when speaking of the history of the Netherlands, in the Netherlands. I will not delve into the position that the Netherlands played within the slave trade, as that would be a completely different kind of article.

Sinterklaas today

Non-Dutch people seem to have a problem with the tradition of Sinterklaas, which can be really confusing to Dutch people. Black Pete was never meant to be racist or even discriminative; however, people perceive him that way. To say that the problems with this tradition are something of the last decade, or maybe even the last century, would be incorrect, as discussed above with the complaints from the pastor from Gouda. Even a simple search online would indicate that different cultures living in the Netherlands don’t always appreciate or understand our tradition (Helsloot 1996; Simons 1996, 1998; Grimes 2005). It seems that at any given time in the history of the tradition, someone seemed to have a problem, and many changes have been made to accommodate those that do not agree. For example in the late 19th to early 20th century Sinterklaas was accompanied by one male Black Pete (Schenkman 1907). He is now accompanied by hundreds of Petes, both male and female. Not only has Pete multiplied, there is now a Pete-School, where the Petes learn how to wrap presents and throw candy. There has even been delegation, as there is a navigation-Pete, a package-Pete, a pepernoten-Pete etc. In the end it turned out that it was not the UN that declared an investigation, but people working within a voluntary department of the UN who do not agree with the tradition and support the idea that ‘Zwarte Piet is racisme’ (Black Pete is racism). It started a big debate in the Netherlands of huge proportions, as the Facebook page ‘Pietitie,’ to save Black Pete reached over 1 million likes within 24 hours which is quite a feat for a country of only 17 million people (RTL Nieuws, 2013). This year, the Saint made his normal entry into the country with his Petes, the only difference being that they were not wearing their big hooped earrings. Slowly but surely the tradition is changing, which indicates that the Netherlands accommodates all cultures that reside there, and still wants to hold strong to the values and principles of tolerance which made the country such an international refuge and success in the international trading market.

Sinterklaas vs. Santa Klaus

Most non-Dutch people confuse Sinterklaas with Santa Claus; both festivities are celebrated in the Netherlands. However if you want to know the difference between the two, just ask about, any young child will tell you that they are not the same person, as Sinterklaas lives in Spain and Santa Klaus on the North Pole, although both characters are based on the same saint. Whilst carrying out the research for this article, I have learned that Dutch people had a hand in creating Santa Claus. A long time ago, the Dutch had a colony they called New Amsterdam, which most people know today as New York. The Dutch colonists wanted to keep the Dutch spirit going, in the sense of freedom of speech, religion and tolerance. However, celebrating a Catholic Saint did not seem to fit that picture, so the date and the appearance of the Saint was adjusted and a jolly ‘fat’ man was created who went by the name Santa Claus (Helsloot 1996; Grimes 2005).

Conclusion

Black Pete is a relatively new companion to Sinterklaas, however this does not make him less loved and appreciated, as my young niece and nephew will be able to vouch for, as well as many other children in the Netherlands. His origins might be vague, but never intended to hurt anybody, resulting in changes and possibly more, to his/her appearance over the next few years, which will hopefully be accepted. However I believe that if Black Pete stays, no one will make too much of a fuss (the founders of ‘Black Pete is racism’ excluded). There is a connection between Saint Nicholas, Sinterklaas and Santa Claus; however, they are not one and the same person. Despite what will happen, I know one thing for sure: I will keep loving the festivities surrounding the tradition, and the food that accompanies it. No matter what happens, to me, it will always be Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet!

If you wish to discuss this issue, please try and uphold the Dutch values of respect for freedom of speech, religion and tolerance.

Bibliography

- ANP. (2013a) Verenigde Naties onderzoeken Zwarte Piet. www.nu.nl. Available at: http://www.nu.nl/binnenland/3606121/verenigde-naties-onderzoeken-zwarte-... [Accessed 19/10/2013].

- ANP. (2013b) Onderzoek Verenigde Naties naar Zwarte Piet. Algemeen Dagblad. Available at: http://www.ad.nl/ad/nl/1012/Nederland/article/detail/3529908/2013/10/19/... [Accessed 19/10/2013].

- Anon (n.d.) Who is St. Nicholas. [Online] St. Nicholas Center. Available at: http://www.stnicholascenter.org/pages/who-is-st-nicholas/ [Accessed 23/11/2013].

- Boer-Dirks, E. (1993) Nieuw licht op Zwarte Piet. Volkskundig Bulletin. 19. 1 – 35

- Fontein, J. (2013) Zwartepietpetitie op Facebook naar 1 miljoen likes. Volkskrant. Available at:

http://www.volkskrant.nl/vk/nl/2686/Binnenland/article/detail/3531937/20... [Accessed 23/10/2013]. - Grimes, W. (2005) Following Santa to the Ends of the Earth. The New York Times, 30/11/2005. 8

- Helsloot, J. (1996) Sinterklaas en de komst van de kerstman. Volkskundig Bulletin. 22. 299-329

- RTL Nieuws. (2013) In recordtempo miljoen likes voor Pietitie. [Online] RTL Nieuws. Available at: http://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/binnenland/recordtempo-miljoen-likes-voor... [Accessed 23/10/2013].

- Scheer, A.-J. (2013) Zwarte Piet is nooit een slaaf geweest. Volkskrant, 15/10/2013.

- Schenkman, J. and Geldorp, P. J. A. C. (1907) Sint Nicolaas en zijn knecht. J. Vlieger.

- Simons, M. (1996) For Abused Saint, the Last Straw: Santa Weighs In. The New York Times, 11/12/1996. 4

- Simons, M. (1998) A World of Celebration; Amsterdam: St. Nicholas Day. The New York Times, 8/11/1998. 14