Introduction

The first traces of fire have been discovered in the Swartkrans Cave in South Africa and they date approximately 1.5 million years ago. Once humans developed the ability to initiate and control fire, they utilised it for their own needs, such as warmth and cooking, and later, for more complex processes, such as making vessels from clay. One such purpose was the creation of high-quality vessels that could be used for ritual or practical purposes (symposia). The process of firing the vessels inside the kiln (Apex, note 2) was a rather difficult task because it required a stable temperature coupled with the supply or lack of oxygen in the firing chamber (for the vases’ firing process see Cook R. M. 1994, Scheibler I. 1992, 127-128, Noble J.V. 1965 and Ιακωβίδης Σπ. 1969) (Apex, note 3). The limited ways of controlling the kiln’s temperature made the process even more challenging. The “Vanausoi”, professional craftsmen associated with this process, were experienced and knew to how to track and control the kiln’s temperature.

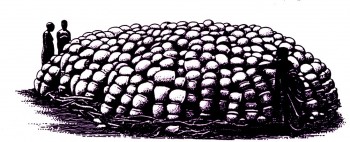

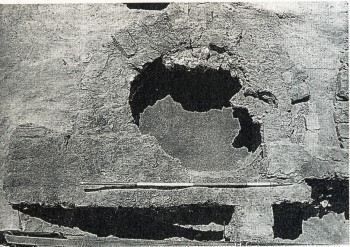

The first kilns were used in the Near East around 8000 BC. to produce cereals and bread (Renfrew C.-Bahn P. 2001, 346). The primitive way of firing the vases was one of the "open" fires (Forbes R. J. 1966, 69, Singer C., Holmyard E.J., Hall A.R. 1979, 391) (fig.1). In this method, large pits were opened on the ground, filled with fuel, such as wood, grasses, seeds etc. The vases were placed on the fuel covering every available space. However, this method proved inadequate; the majority of vessels were being destroyed due to the lack of stable temperature. The first kilns were used exclusively for the production of vases were constructed in Susa, c. 4000 B.C. (Singer C., Holmyard E.J., Hall A.R. 1979, 394, Forbes R. J. 1966, 70) (fig.2). They were vertical making it possible to achieve a stable and high temperature. The Egyptians at c. 2700-2500 B.C. developed this type of kiln mainly for the production of glass (fig.3). In Greece, the oldest kiln was discovered in Olynthos and dates back to 3000 B.C. (Cook R. M. 1961, 65, Ορλάνδος A. K. 1955, 92, note 2, Mylonas G. 1929, 12-18, Robinson M. D. 1929 58, fig.6).

Kiln literature references

The kiln is referred numerous times in the ancient literature. Some of the earliest literary testimonies surviving today are texts in cuneiform writing (Forbes R. J. 1966, 70). In these texts, various kiln types have been identified based on the material used. For instance, the oven, referred to generally as “utûnu” or “atûnu”, was originally used in the kitchen for the heating of malt, though it has been noted to have also been used for melting metals, and the firing of tiles and bricks. The terms “kîru” or “kûru” (Akkadian) are used to describe the kiln mainly used to produce glass and melt metals. While the terms “kiškittu/kiškattu” and “nasrapu/našrapu” (Akkadian) associates with kilns primarily used for firing bricks and melting metals, respectively’ (Apex, note 4). The ceramic kiln is also encountered in the ancient Greek literary sources with plenty of different names (Apex, note 5), such as hipnós (ιπνός) (Apex, note 6), krivanos (κρίβανος) or klivanos (κλίβανος) in the Doric dialect), furnace and pnigeus (πνιγεύς) (Apex, notes 7,8,9 respectively).

The most known and complete reference in the ancient Greek literature about the kiln and the dangers of firing the vases is lying in a poem of Ψευδο-Ηρόδοτος (Noble J. V. 1965, 102-113 and Scheibler I. 1992, 253, note 48 and here Apex, note 10).

Conditions for Construction

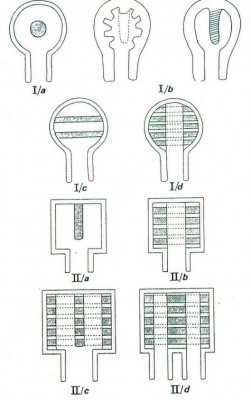

The location where the kiln was best to be built was chosen carefully as it was mandatory to meet certain criteria. One of the most important prerequisites was its construction at the outskirts of the settlements, so ensure there was no danger of smoke disturbing it. An equally important criterion was possessing a sufficient quantity of fuel and water required to dilute the clay. The ground also needed to be soft so the kiln could be constructed with a natural inclination to facilitate adequate air circulation (Δαβάρας Κ. 1973, 112). The shape (for the kiln’s typology see Cuomo di Caprio N. 1992, 71, 74, 84 - fig.4) - circular, ellipsoid or rectangle - and the size of the kiln varied according to the season (Apex, note 11) that it had been built and the size of the production was destined to carry out.

Kiln’s Typology

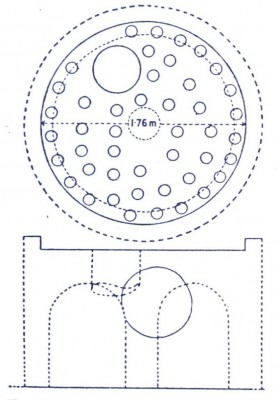

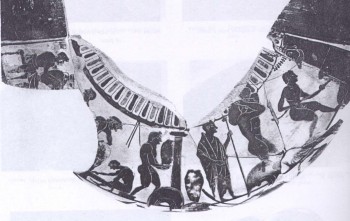

The kilns’ general type (fig. 4; Cuomo di Caprio 1992, 71, 74, 84) and shape was simple and has been depicted on clay tables several times (fig.5) (Antikenmuseum Berlin 1988, Geagan H. A. 1970, Humfry P. 1971, 116-7, Τσούντας Χρ. 1928, 170-1, Noble J. V. 1965, 72-4, fig. 231-8, Cook R. M. 1961, 64-5, Scheibler I. 1992, 126, 129, fig. 92, 94-96), on vases (fig.6, Museum collection number: J731, Beazley Online database vase number: 302031) (indicatively ABV 362.36, 520.26 & 256.26, Beazley J. D 1946, 6, Beazley J. D. 1993, 107, ARV 676.17, Mannack T. 2003) and semi-precious stones (Blümner H. 1969).

the kiln’s opening to create a reductive environment

(https://www.flickr.com/photos/130870_040871/33465480171/in/photostream/).

Internal Structure

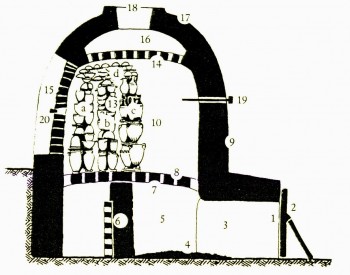

According to the typical pattern (fig.7), a kiln consisted of two separated chambers, placed underground and one above the ground. An essential part of a kiln was the one called “δρόμος” (or praefurnium, stokehole, foyer, heizraum-for terminology Δαβάρας K. 1973). It was a narrow aisle formed as part of the underground chamber with which it was connected, though the length of the aisle could vary significantly. This is where the fuel was placed. The underground chamber, known as the firing chamber (or laboratory, kiln chamber, chamber de caisson, the chamber di cottura, the Brennraum) differentiated in dimensions and shape. It had a relatively thick, perforated floor made of clay, called "grid" or "βάτο" (or perforated / firing floor, sol à orifices, Lochtenne) and a central pillar with arcs in a radial arrangement. The hot air was circulated in this underground, tunnel-shaped space and through the “grid” holes to reach the above-ground chamber, where the vases were stacked carefully. This chamber was covered with either a hemispherical or horizontal ceiling, which rarely survives.

Legend: 1. Opening for firing, 2. Fireproof door, 3. Fuelling aisle (dromos/ δρόμος),

4. Fuel, 5. Underground chamber (Firing chamber), 6. Central pillar 7. Perforated clay floor (batos/μπάτος/εσχάρα), 8. Clay floor’s openings, 9. Outer kiln lining, 10. Above ground

chamber (Burning chamber), 13. Piled vases, 14. Intermediate covering

15. Auxiliary opening built with bricks, 16. Smoke collection area, 17. Vault, 18. Ventilation hole, 19. Control holes.

For example, in Greece, the kilns’ ceilings are imitating the Mesopotamian ones (fig.8-Hodges H. 1970, 70, fig. 51, Nicholson P. T. and Shaw I. 2000) whereas in Egypt they are horizontal (Δαβάρας Κ. 1973, 77). The size of the ceiling varied, albeit was usually proportionate to the chamber’s diameter. In the lower part of the chamber, an opening was placed to regulate the air supply (Κονοφάγου Κ., Παπαδημητρίου Γ. 1981) to create either reductive or oxidative environment in the chamber (Apex - note 3). At the ceiling, there was an opening for the smoke. Kilns were initially made of clay and on a later stage, they were made of bricks.

Kiln Manufacturers

At this point, it would be useful to refer to those who constructed the kilns. Scheibler (1992, 123) mentions that kiln makers were the potters themselves. This would probably occur during the first period but as the demand for massive pottery production was increasingly growing (especially in large settlements or large urban centres) the potters would have found themselves overwhelmed. This is the time where a class of "professionals" would have arisen to build kilns for the favour of ceramic workshops or individuals. In literary sources (see the corresponding entries in LSJ) they are mentioned as “ipnoplathai” (ιπνοπλάθαι-Πλάτων Θεαίτητος 147α, 1-5, Πολυδεύκης Ονομαστικόν, 7, 163, Αρποκρατίωνας Λέξεις των δέκα ρητόρων, λήμμα «Ιπνός»), “ipnoplastai” (ιπνοπλάσται-Γαληνός Θρασύβουλος, 896-7) and “ipnopoioi” (ιπνοποιοί-Λουκιανός Προμηθεύς, 2, 12, Θεμίστιος Βασανιστής, 21, 256d, 9). The craftsmen who were responsible for placing the vases in the chamber and firing them were known as "Vanausoi" (βάναυσοι-Λεξικό Σούδα, λήμμα «βάναυσος»). The vases’ placement was a very skilful task which had to be undertaken carefully with the help of wedges (Papadopoulos J.K. 1992). The small (vases) were placed within the larger ones to save space within the fire chamber. "Vanausoi" were professionals and, as mentioned in the introduction, were able to maintain and adjust the kiln’s temperature by experience. During the firing process, many things could go wrong and destroy the vases, such as the wrong estimation of the firing chamber’s temperature and vases not placed correctly and as a result, to get stuck together. For that reason, the "Vanausoi” “were placing apotropaic masks in forms of demons or bad spirits (...) or hanging branches of an olive tree, supposedly attracted to the spirits of consistency" (Scheibler 1992, 122-translation made by the author).

Conclusion

Since the discovery of fire over a million years ago, the human had always been trying to set it under control and use it for its benefit. For example, this could be for cooking food, firing pottery vases and plinths and create glass. The first kilns were made in 8000 BC in Near East and throughout their history, they have been evolved in an attempt to stabilize the fire and reach a higher temperature. Their shape could variate regarding their use or chronology but their general structure remained the same until today if we considerate an example of a modern kiln located in Mantamados, Lesvos island, north-eastern Greece (fig.9-Apex, note 12-Γιαννοπούλου Μ., Δεμέστιχα Σ. 1998). In the early stages of pottery making, kilns were constructed by the potters themselves but as the demand for vases was growing the need for a working-class which specializes in building kilns emerged, named “ipnoplathai”. The placement of the vases within the kiln and the control of the firing process was a very demanding and responsible task and required a lot of experience so the hard work of the potters do not get wasted. This task used to be undertaken by “Vanausoi”. Kilns have been depicted numerous times and so are their references in ancient Akkadian and Greek literature. Our knowledge about kilns also comes from archaeological remains and, remarkably, some of them are well-preserved (Δεσποίνη Α. 1982). The most suitable place to establish a kiln and a pottery workshop was chosen carefully and should meet certain criteria. The study of the kilns’ size and workshops’ location and can provide us with valuable information about the size of pottery production and distribution revealing trade connections with other areas. This area of study is still under development and has a lot to offer to the academic community.

Acronyms

AAA - Αρχαιολογικά Ανάλεκτα Αθηνών (Archaeological Analects of Athens)

AΔ - Αρχαιολογικό Δελτίο (Archaeological Bulletin)

AΕ - Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς (Archaeological Newspaper)

ΠΑΑ - Πρακτικά Ακαδημίας Αθηνών (Proceedings of the Academy of Athens)

AA - Archäologischer Anzeiger

AM - Athenische Mitteilungen

ABV - J. D. Beazley. Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters. Oxford, 1956

AJA - American Journal of Archaeology

AR - Archaeological Reports

ARV - J. D. Beazley. Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford, 1963

BCH - Bulletin de correspondance hellénique

CVA - Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum

HESP. - Hesperia: Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

JdI - Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts

JHS - Journal of Hellenic Studies

LSJ - Liddell and Scott, Greek-English Lexicon, 9th ed., rev. H. Stuart Jones (1925–40); Suppl. by E. A. Barber and others (1968)

Medit. Arch. - Mediterranean Archaeology

TLG - Thesaurus Linguae Graecae

Apex- Notes

1. The article was published in 2011 in Greek in the archaeological journal “Αρχαιολογία και Τέχνες” (Archaeology and Arts) (Δελαβίνιας 2011). The article’s title of the original publication is “Οι αρχαίοι ελληνικοί κεραμικοί κλίβανοι των ιστορικών χρόνων”. The article is a summary of an extensive essay that was undertaken in the spring of 2005, as part of the undergraduate module "Technical Issues: Ceramics and Forms of the Ancient Greek Vases of Historical Times", supervised by Assoc. Professor Chrysiida Tzouvara-Souli, University of Ioannina.

The ceramic kiln is a humble (in terms of material) two-storey structure of 2-3 m. high. It is essentially a kind of oven. Kilns have been found in many places across Greece. An indicative list of furnaces can be found at Cook R. M. 1961).

Adjustment of the amount of the incoming air in the kiln’s chamber, allowed the kiln maker to create either reductive or oxidative environment within it. The presence or the absence of air in the chamber during the firing process combined with a specific substance laid on vases was crucially affecting the quality and the type of vases for production (black or red-figured vases).

It should be noted that the correspondence of the above terms with specific types of kilns should not be taken strictly into account. Firstly, because the ancient texts are often vague on this subject and secondly because there were kilns did not have only use, which is obvious, especially in the first period of their existence. The same applies to the ancient Greek literature (see below).

The “Musaios” project (Musaios 2020) was used as a source for the ancient Greek literature. The references of kiln terms are numerous. For example, the corresponding entries in the etymological dictionaries Genuinum, Gudianum, Magnum and Parvum as well the Souda dictionary and the LSJ.

Ησύχιος Λεξικόν, the corresponding entry. The term in addition to its importance as a cooking or ceramic furnace (Ηρόδοτος Ιστορία, 5, 92, Αριστοφάνης Σφήκες, 138-140, Ιπποκράτης Περί Νουσών, 2, 47, 41, Γυναικείων, 1, 91, 13, Επιδημιών, 4, 1, 20, 32, Αθήναιος Δειπνοσοφιστές, 2, 54, 2-4), also meant the area of the kitchen (Σιμωνίδης Περί γυναικών, 7, 61. Αριστοφάνης Σφήκες, 139, 837. Λυκούργος, 73), the lamp (Αριστοφάνης Ειρήνη, 841, Πλούτος, 815), and the dunging area (Κώκαλος, Θεσμοφοριάζουσαι, απόσπ. 353. Πολυδεύκης Ονομαστικόν, 5, 91, 2.

Zenon served as commander of Fayum until 248/7 B.C. He was a Caissus immigrant from Caunus, who went to Fayum in 256 B.C. and he stayed there after 248/7 B.C., so his service was over), and the papyrus that we have saved contains, among other things, a detailed record of revenues and expenses and are, thus, an important source of information for the administrative system of the land of Apollonius, which has constant demands for money. This papyrus dates back to 257 B.C. In addition to its importance as a furnace (Ηρόδοτος Ιστορία, 2, 92, 5) on Zenon. It also meant the cavity of the rock (Αιλιανός Περί Ζώων Ιδιότητος, 2, 22, 13), a funnel vase for the abstraction of water (Στράβωνας Γεωγραφικά, 16, 2, 13) and a funnel vase, in which the bread was baked (Ηρόδοτος Ιστορία, 2, 92, 23).

The term had the meaning of the oven used for the firing of vases (Ηρόδοτος Ιστορία, 4, 164, 12 and 1, 179, 6, Αισχύλος Ωρείθυια, απόσπ. 280), the meat (Ηρόδοτος Ιστορία, 1,133, 5), and as a mean for heating the space, (Γαληνός Υγιεινή, 6, 146).

This term was used by the Κωμικούς (Etymologicum Gudianum, Souda dictionary corresponding references).

The poem is titled "Κάμινος" (Ψευδο-Ηρόδοτος Βίοι Ομήρου, 32, αποσπ. 302).

Gebauer K. and Johannes H. supported that the shape is closely related to the time the kiln was built (Δεσποίνη Α. 1982, 83, notes 3, 4). However, Δεσποίνη believes that the shape was adapted to the specific conditions of the kiln’s construction site (Δεσποίνη Α. 1982, 84).

A village located on Lesvos island, in Greece.

Greek Bibliography

Beazley, J. D. (1993) Η εξέλιξη του αττικού μελανόμορφου ρυθμού. Αθήνα: Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Βιβλιοθήκη της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας), p. 107.

Cook, R. M. (1994) Ελληνική αγγειογραφία. 3rd edn. Αθήνα, p. 315.

Renfrew C., B. P. (2001) Αρχαιολογία, θεωρίες, μεθοδολογία και πρακτικές εφαρμογές. Αθήνα : Καρδαμίτσα , p. 346

Scheibler Ι. (1992) Ελληνική Κεραμική. Αθήνα : Καρδαμίτσα, pp. 127–128.

Γιαννοπούλου Μ., Δεμέστιχα Σ. (1998) Τα εργαστήρια αγγειοπλαστικής της περιοχής Μανταμάδου Λέσβου. Αθήνα : Κέντρο Μελέτης Νεώτερης Κεραμεικής.

Δεσποίνη Α. (1982) ‘Κεραμικοί κλίβανοι Σίνδου’, ΑΕ, (121), pp. 61–84.

Δαβάρας Κ. (1973) ‘Μινωϊκή κεραμεική κάμινος εις Στύλον Χανίων’, ΑΕ, (112), pp. 75–80.

Δελαβίνιας, Π. (2011) Οι αρχαίοι ελληνικοί κεραμικοί κλίβανοι των ιστορικών χρόνων, Αρχαιολογία Online. Available at: https://www.archaiologia.gr/blog/2011/10/26/%CE%BF%CE%B9-%CE%B1%CF%81%CF... (Accessed: 16 April 2020).

Ιακωβίδης, Σ. (1969) ‘Η μελανή βαφή των αρχαίων αγγείων’, ΑΑΑ, (2), pp. 269–274.

Τσούντας Χ. (1928) Ιστορία της Αρχαίας Ελληνικής Τέχνης. Αθήνα : Επικαιρότητα, pp. 170–171.

Foreign Language Bibliography

Beazley, J. D. (1946) ‘Potter and painter in Ancient Athens’, Proceedings of the British Academy, (30), p. 6.

Berlin, Α. (1988) Die ausgestellten Werke. Edited by Staatliche Museen. Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

Blümner Η. (1969) Technologie und Terminologie der Gewerbe und Künste bei Griechen und Römern. Hildesheim, pp. 51–53, fig. 12–3.

Cook, R. M. (1961) ‘The double stocking tunnel of Greek kilns’, BSA, (56), pp. 64–67.

Di Caprio N., C. (1992) ‘Les ateliers de potiers en Grande Grèce’, BCH, (23), pp. 69–85.

Dumont, D. J. and Smith, R. M. (2010) MUSAIOS: Software for TLG and PHI CD-ROMs. Available at: http://www.musaios.com/ (Accessed: 16 April 2020).

Forbes, R. J. (1966) Studies in Ancient Technology. 2nd edn. Leiden : E J Brill, pp. 69-70.

Geagan, H. A. (1970) ‘Mythological themes on the plaques from Penteskouphia’, AA, (85), pp. 31–48.

Humfry, P. (1971) Necrocorinthia. A Study of Corinthian Art in the Archaic Period. 2nd edn. Maryland, pp. 116–117.

Mylonas, G. E. (1929) Excavations at Olynthus Part I: The Neolithic Settlement. Baltimore, pp. 12–18.

Noble, J. V. (1965) The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery. New York: London, Faber, pp. 60–1, 72–4, 102–13.

Papadopoulos, J. K. (1992) ‘Λάσανα, Tuyeres, and kiln firing supports’, HESP., (61), pp. 203–221.

Robinson, M. D. (1929) A Preliminary Report on the Excavations at Olynthos, JSTOR. Archaeological Institute of America. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/497648 (Accessed: 16 April 2020).

Singer C., H. E. J. (1979) A History of Technology. Edited by A. R. Hall. Oxford University Press, p. 391.

Mannack T. (2003) Browse Data: XDB: The Classical Art Research Centre and The Beazley Archive, Beazley Archive Pottery Database (BAPD). University of Oxford. Available at: www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/68A4A755-C32D-4E99-AF90-43367621E6D5 (Accessed: 16 April 2020).

Hodges H. (1970) Technology in the Ancient World. New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing, p. 37, fig. 51.

Nicholson P. T. and Shaw I. (2000) Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press, fig.6.